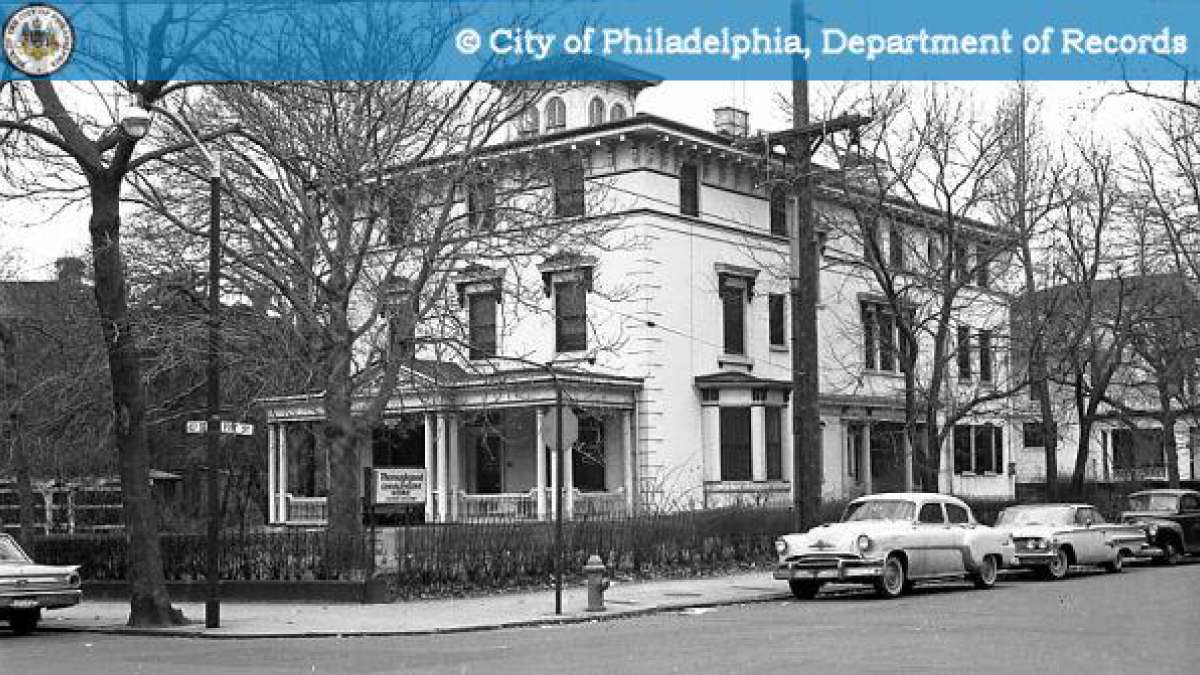

Historic 40th & Pine house meets the wrecking ball [photos]

First, the building on the southwest corner of 40th and Pine streets was a private home for a rich Philadelphian. Then it was a residence for sick elderly people. Later, when it was an empty shell owned by the University of Pennsylvania, it was the subject of a protracted legal battle between Penn and a group of neighbors who wanted to preserve it.

Now it’s being destroyed, and one day Penn will replace it with an apartment complex for graduate students.

You could be forgiven for not closely following the 40th & Pine saga over the last few years. It was tedious and sometimes redundant. But we’d feel derelict if we didn’t mark its conclusion with a couple reflections on what we learned.

HARDSHIP FOR THE RICH

The University of Pennsylvania is a wealthy institution. It has money to spare. It could have spent some of that money restoring the old mansion, built in the 1850s, or converting it into dorms, condos, apartments, a halfway house, or a homeless shelter. But it didn’t have to.

Philadelphia’s preservation ordinance requires owners of historic buildings to prove a number of specific things before they can get permission to demolish. They have to prove that the sale of the building is “impracticable,” for example, and that other potential uses are “foreclosed.” In this instance, the courts felt that Penn had met those standards.

Historic-property owners can win hardship designations even if they’re not the kind of people or institutions we associate with hardship. The legal standard isn’t whether a hypothetical person with unlimited funds can preserve a building, as Penn’s lawyers argued at one point. It’s whether the owner has shown that he or she has exhausted every reasonable reuse option, with the definition of reasonable changing from case to case.

SUPPORT FOR PRESERVATION VS. OPPOSITION TO DEVELOPMENT

There were times during the 40th & Pine battle when it was hard to tell whether neighbors were trying to preserve the building because it added something to the neighborhood or whether they were trying to preserve it because it was stopping Penn from building something bigger. Both of those impulses, to preserve something historic or to oppose a development, are defensible. But they’re defensible for completely different reasons, and it wasn’t always clear during the legal proceedings which impulse was at work.

Which is not to say that Penn’s opponents had an easy argument to make. Penn wanted to tear down the building because it said it wasn’t useable, on the one hand, and because it wanted to build a new student housing complex on the other hand. Neighbors were opposed because, they said, they wanted to keep the building standing, and because they didn’t want the new building to be built. At the same time the courts were considering appeals of the Historical Commission’s decision, they were dealing with a separate set of appeals from the zoning board, which had approved Penn’s development plans. The latter appeals are still ongoing.

But both sides revealed their positions as partially untrue in the fall of 2013, when Penn offered a compromise plan that would have kept the building standing. In an effort to end the litigation, the University said it would preserve the mansion and build five stories of student housing around it. The neighbors declined the offer.

While it didn’t come to pass, the incident reveals two things. For one, Penn had in fact not exhausted all of the reuse options for the property. Secondly, the neighbors weren’t chiefly interested in preserving the building because of its historic value.

“Historic preservation of the mansion itself was always a prime focus of our efforts,” said Paul Boni, an attorney representing the Woodland Terrace Homeowners Association and others who appealed the demolition permit. “But we had other goals also, to respect the scale and density of the neighborhood.”

Matt McClure, an attorney representing Penn, didn’t respond to a request for comment.

PRIVATE INTERESTS USUALLY WIN

This is almost too obvious to print, but the cards are always stacked in favor of property owners. Even though we have laws like zoning codes and preservation ordinances, permanently preventing property owners from using their land in the way they want is not a significant part of the American legal tradition. That’s more true for wealthy landowners, who can afford long legal battles, and less true for poor ones, who can’t pay for years of litigation, and whose properties are more vulnerable to eminent domain.

And it’s almost always private interests that drive changes in neighborhoods and cities. Amalgamated property interests, like Penn’s, change neighborhoods even more rapidly. Various mayoral administrations can be more or less assertive about preservation and zoning ordinances, but the loss of significant historic properties can’t be blamed entirely on the Nutter administration. Deference to landowners, to land buyers, is the American way.

Spruce Hill and Woodland Terrace—which used to be part of the Lenapehoking, don’t forget—shouldn’t be too surprised by this outcome.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.