Haddonfield to celebrate its tricentennial in 2013

-

<p>The sun rises just above the horizon at Prime Hook National Wildlife Refuge. (Mark Eichmann/WHYY)</p>

-

<p>(Mark Eichmann/WHYY)</p>

-

<p>(Mark Eichmann/WHYY)</p>

-

<p>(Mark Eichmann/WHYY)</p>

-

<p>(Mark Eichmann/WHYY)</p>

-

<p>(Mark Eichmann/WHYY)</p>

-

<p>(Mark Eichmann/WHYY)</p>

-

<p>(Mark Eichmann/WHYY)</p>

-

<p>Cranes and other birds stand in shallow water at Prime Hook. (Mark Eichmann/WHYY)</p>

-

<p>This sign marks the end of the line at Fowler Beach. The dune breach can be seen in the background. (Mark Eichmann/WHYY)</p>

-

<p>Water from the Delaware Bay flows past what used to be sand dunes at Fowler Beach. The salt water is changing the make up of the refuge. (Mark Eichmann/WHYY)</p>

-

<p>(Mark Eichmann/WHYY)</p>

-

<p>Johnson House Executive Director Cornelia Swinson recognizes Germantown High School senior Aliyah Muhammad who designed an historic tour of the Johnson House as part of her senior internship. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)</p>

-

<p>Baba Garland M. Franklin, a percussionist with Temple University's Pan-African Studies Community Education Program (PASCEP), drums at the Johnson House Kwanzaa celebration. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)</p>

-

<p>Levi Joynes, a percussionist with Temple University's Pan-African Studies Community Education Program (PASCEP), drums at the Johnson House Kwanzaa celebration on Thursday night. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)</p>

-

<p>Saundra "Momma Sandi" Gilliard, president of African Storytelling group Keepers of the Culture, gives a Kwanzaa presentation at the historic Johnson House in Germantown. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)</p>

-

<p>Denise Valentine, a storyteller with Keepers of the Culture, tells a Kwanzaa story at the historic Johnson House in Germantown. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)</p>

-

<p>A Hadrosaurus statue is prominently displayed on Kings Highway in Haddonfield. The original skeleton is on display at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia. (Bethany Mitros/for NewsWorks)</p>

-

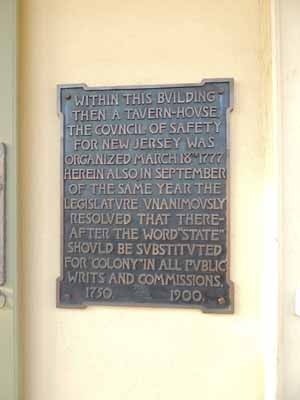

<p>A plaque outside the Indian King Tavern announces its importance to passerby. (Bethany Mitros/for NewsWorks)</p>

-

<p>As part of Haddonfield's Tricentennial celebration, the Indian King Tavern will host a reading of the Declaration of Independence on the Fourth of July. (Bethany Mitros/for NewsWorks)</p>

-

<p>Downtown Haddonfield (Bethany Mitros/for NewsWorks)</p>

-

<p>Indian King Tavern (Bethany Mitros/for NewsWorks)</p>

-

<p>Haddonfield's first Quaker Meeting House was erected in 1721, but the current brick building was built in 1760. (Bethany Mitros/for NewsWorks)</p>

-

<p>This room at the Indian King Tavern hosted New Jersey's General Assembly during the Revolutionary War in 1777. (Bethany Mitros/for NewsWorks)</p>

-

<p>Without the plaques at the end of a dead end street off of Grove Street in Haddonfield, the marl pit where the Hadrosaurus skeleton was excavated would look just like any other woodsy area.</p>

Haddonfield’s First Night is known for its fun, family friendly celebration of the arts, but this year’s First Night will be especially meaningful as Haddonfield kicks off its 300th anniversary year.

The tricentennial celebration of Haddonfield’s rich history, which includes revolutionary characters, ideas and discoveries, will continue throughout 2013, as the town honors the year that famed settler Elizabeth Haddon built her home on the land now known as Haddonfield.

Elizabeth’s father, John Haddon, sent her to America at the age of 21, as a single Quaker woman with the Power of Attorney necessary for her to begin to execute his dream of building a free Quaker community in America as religious persecution ran rampant in England, said Kathy Tassini, Haddonfield historian and co-author of “Images of America: Haddonfield,” and “Lost in Haddonfield.”

Though the choice to send Elizabeth alone ahead of the rest of the family was “pretty unusual,” Tassini explained that “it was clear from an early age that Elizabeth was smart.” Her father educated her at home in law, reading and business and he must have had “infinite trust in her ability to execute his wishes.”

In America, Elizabeth married Quaker minister John Estaugh and they worked to establish her father’s dream of creating a Quaker community in the free world, but he “didn’t take over for her.” Estaugh was “roped into business dealings,” said Tassini, but his heart was with the Quaker religion. He “loved to preach the truth and love of Quakerism.”

Elizabeth and John never had any biological children, but Elizabeth’s nephew, Ebenezer Hopkins came to Haddonfield and became the heir to the Haddon fortune in America. Though Ebenezer predeceased Elizabeth, his seven children helped to solidify the family’s legacy.

What made Elizabeth Haddon’s community so successful was that she was willing to build rental properties and sell off smaller lots of land in the interest of establishing the community, explained Tassini. Other early settlers wanted to be “free for themselves,” so they were comfortable just keeping their land. But Elizabeth knew she would need various artisans to settle the area and build a strong community. “It is interesting how single minded she was in pursuing the dream,” Tassini said.

Though the area was “wild and wooly” three hundred years ago, said Tassini, the Quakers came to this area because of the availability of land. Some even knew William Penn in England as they shared the same philosophy that the Quakers needed a place to freely practice their religion.

Day to day life probably included clearing and farming the land and going to Quaker meetings. The families in the area were large, but there were not a lot, said Tassini. Only two properties in Haddonfield were occupied in 1713.Haddonfield’s community grew as the years progressed. By the Revolutionary War, Haddonfield was known as a market town. It was surrounded by working apple orchards with the main goal of pressing cider, the least expensive alcoholic beverage at the time, said Garry Stone, historian for the Indian King Tavern in Haddonfield.”The village of Haddonfield was the biggest around but it was still very tiny” with only around 40 families, explained Stone.

But one of its most notable achievements came in 1777, when the Indian King Tavern became the meeting place for New Jersey’s General Assembly from January to September. During this time, Haddonfield became the capitol of New Jersey, which sounds more impressive than it is, said Stone, because they only required two rooms.

Still, the General Assembly passed a number of important measures during this time. When New Jersey’s constitution was approved in 1776, it included a clause that if the colonies were to reconcile with England, the constitution would be null and void, however, in 1777, it was clear that was not going to happen. At a meeting of the General Assembly at Haddonfield’s Indian King Tavern, the clause was voted null and void and all the references to “colony” within the constitution were changed to the independent “state.”

“As the revolutionaries struggled to fight the war, Haddonfield and the Indian King Tavern helped to strengthen the voice of freedom,” said Stone.

Haddonfield’s history extends beyond the Revolutionary War. In 1858, William Foulke excavated an almost complete skeleton of a dinosaur, later named the Hadrosaurus, from a marl pit in Haddonfield. It was first almost complete dinosaur skeleton to be discovered in America and only the second one worldwide.

Haddonfield also boasts the second oldest volunteer fire company in the United States. It is the hometown of actress Joanna Cassidy and the author of the classic movie Halloween, Debra Hill. Steven Spielberg lived in the area for a short time, and many Philadelphia athletes have made Haddonfield their home.

Both Tassini and Stone agree that Haddonfield’s success was due to its location. In 1713, it was a two day trip to travel from Burlington to Salem, and Haddonfield was mid-way between the two settlements. Kings Highway also meets with Cooper River at the tip of Haddonfield’s boundary, so it helped encourage people to come and practice their trades because it was accessible from land and water.

Haddonfield will celebrate its history all year long with events at the Quaker Friends Meeting House, the Indian King Tavern, and other historic locations in town. The Tricentennial committee is also planning to promote a volunteer initiative called 300 Days of Service.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.