Going to school in Kensington amid drug crisis: ‘We need to be beacons of hope’

Schools in Kensington strive to be safe havens from violence and drug use, while also helping kids deal with the emotional trauma they carry inside.

Listen 4:47

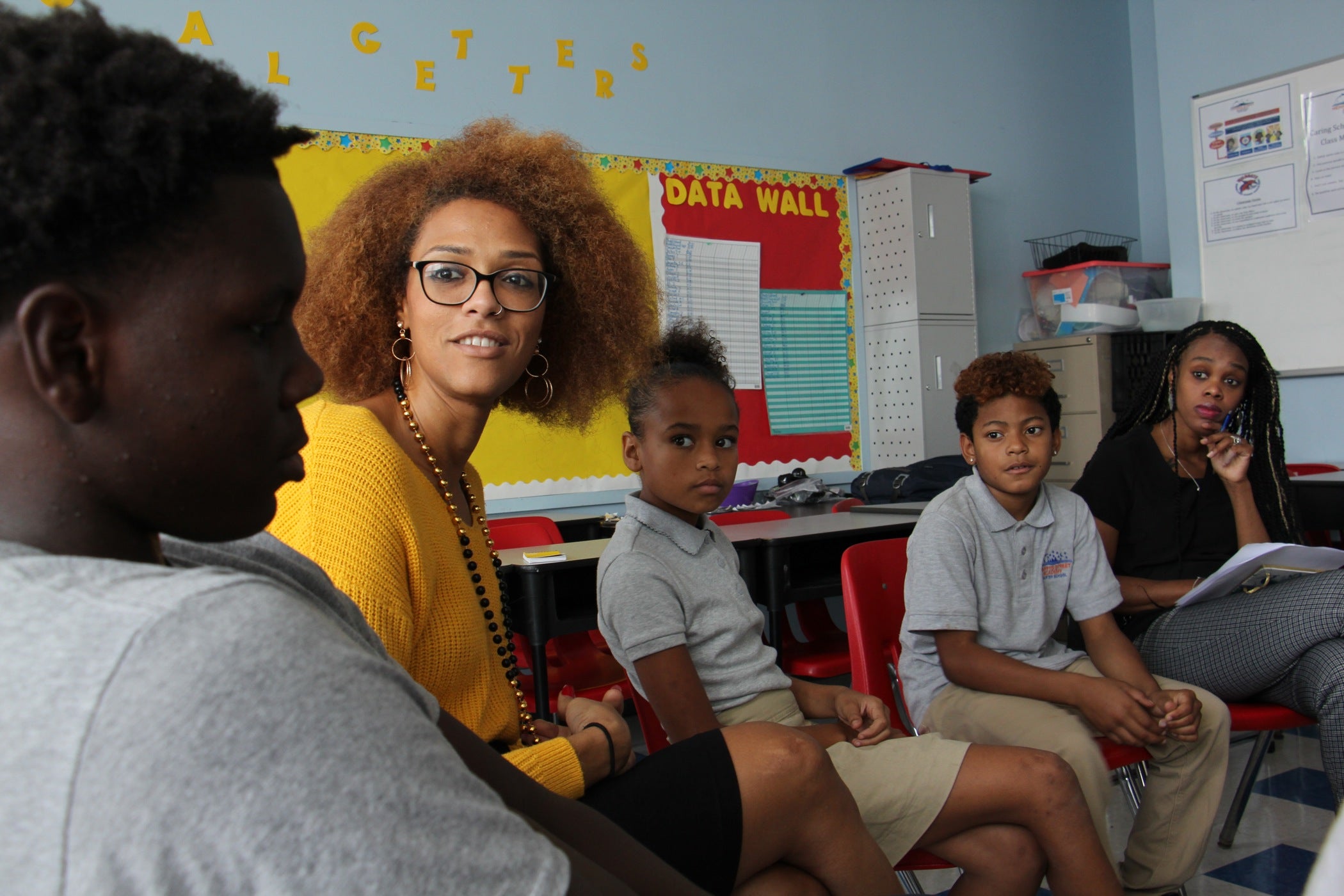

Students at Memphis Street Academy raise their hands during a student wellness meeting. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

How do we help children thrive and stay healthy in today’s world? Check out our Modern Kids series for more stories.

In a conference room at Lewis Elkin Elementary School, principal Charlotte Maddox stood at a laptop, flipping through photos that she projected on a screen in front of her — pictures of things not typically associated with grade school.

Used syringes collected in a jar. A man sprawled unconscious on the playground. The shattered window of a teacher’s car, which had been hit by a stray bullet. Slide after slide collected images of a school under siege by the opioid crisis.

Beginning at 6 a.m. each school day, Maddox explained, custodial staff and a school police officer scour the school grounds, dispersing homeless people who spend the night there, picking up discarded syringes, and sometimes cleaning up human feces.

Elkin Elementary is in Philadelphia’s Kensington neighborhood, where children step over discarded needles and see people injecting drugs on a daily basis. Schools at the epicenter of the city’s opioid crisis struggle to insulate themselves from the problems outside their walls, while also working to help kids cope with the emotional trauma they carry inside.

“With all of this that’s happening on the outside of the building, we need to be beacons of hope on the inside of the building,” Maddox said.

She strives to make the school a refuge for neighborhood kids.

Still, some parents whose children attend Elkin have concerns about conditions around the school.

“What worries us is we don’t see much security, like police officers or people from the school or the school district helping us in terms of security,” Cristina Garay, whose 9-year-old daughter is a student there, said in Spanish.

In addition to the morning cleanup crew, Maddox said, the school police officer and another staff member patrol Elkin’s grounds during recess. But she acknowledged that the school could use more resources to keep the block clean and safe. The campus is only partially gated, she noted, and most of the fencing is only a few feet high.

The conditions in the neighborhood are causing some families to move away, contributing to a decline in enrollment at Elkin. Overall enrollment there is down by nearly 100 this year, Maddox said. Some of those students transferred to charter schools.

Maddox couldn’t say how much of the decline was due to concerns about safety and quality of life in the area, but she said she had spoken with a number of families who were moving away for those reasons.

“It’s not about the school,” she said. “It’s about what’s happening in the neighborhood.”

When classes let out for the day, students are again surrounded by the fallout of addiction. Once they get home, some are under orders from their parents to remain indoors. Others, like Christia Leiva, a fourth grader at Elkin, are afraid to go outside.

“I tell him to go out to play on the street with the other kids, and he says, ‘No, too much drugs, Mom,’” said Maria Cardona, Christia’s mother, speaking in Spanish. “‘I don’t like it here’ he says. ‘Let’s leave.’ That’s a theme with him, ‘Vámanos.’”

He also asks questions she’s not always sure how to answer.

“Sometimes,” Cardona said, “when he sees people injecting themselves, he says, ‘Mom, what is that they’re putting in themselves?’”

Elkin teachers such as Chelsea Trainor work to address children’s fears about the violence and drug use they witness outside. Each classroom begins the day with a morning meeting, where the teacher invites students to share anything that’s bothering them.

“They’re kind of focused on that in their minds,” Trainor said. “So when it comes time to read, it’s hard for them to look at the words on the page and read because they’re more worried about what happened at home last night, what happened outside their house, what happened on the way to school that morning.”

The meetings also help her learn about serious problems at home she can refer to a school social worker.

A middle school serving children from Kensington uses a similar approach with older students whose understanding of the trauma they experience is growing.

On a recent afternoon at Memphis Street Academy, a charter school for grades five through eight, a dozen students sat in a circle. School counselor Zita Collins led them in a discussion.

“Can I hear a ‘yea’ from anyone who’s been impacted by drugs in this community?” Collins asked.

A staggered chorus of voices chimed in.

“Everyone’s a ‘yea,’” Collins noted.

Daily classroom talks like this are part of a learning effort that supports social and emotional development. The idea is to provide a space where students can share what’s weighing on their minds.

Eighth-grader Benjamin Holt talked about a man who overdosed across the street from his home. He watched as paramedics loaded the dead man’s body onto a stretcher.

“It’s hard to explain the way they just picked him up and threw him on,” Benjamin said. “Personally, I don’t want to see that ever again.”

“That would be hard for even any adult to see,” Collins said.

Seeing something, and saying something about it

Collins listened sympathetically as students described other experiences: family members dying of overdoses; screams outside at night that made it impossible to sleep; drug dealers soliciting them on the street; and accidentally stumbling into someone who was injecting drugs in public.

Traumatic experiences like these can lead to behavior problems and depression in students, school counselors said.

“At the root of all of that is not knowing how to cope with emotions and having to deal with pretty big emotions at a pretty young age,” said Brittany Buchanan, a fifth-grade counselor at Memphis Street Academy.

Buchanan said she spends a lot of her time teaching students how to communicate feelings and techniques like deep breathing and yoga to calm them down.

During the classroom discussion, school CEO Na’imah Holliday-Wimberly encouraged students to join a sports team or a club to extend their stay at school each day. The library would also stay open until 5:30 p.m. to give them a quiet place to get help with their homework, she said.

“We want this place to be a safe haven for you, a place where you can come and just escape all the worries of the world, all the worries of Kensington, all the worries of your neighborhood,” Holliday-Wimberly said.

Memphis Street Academy and Elkin Elementary School are among a couple dozen schools in Kensington grappling with the impact of the opioid crisis. The School District of Philadelphia created a task force last year that meets weekly to support 18 of the most-affected schools.

Currently, the district is working with the city to put taller fencing around Elkin School. Neither the school district nor the city could say when the extended, 8-foot fence would be installed.

“The Managing Director’s Office is in the process of procuring a temporary structure” in the interim, said city spokeswoman Deana Gamble.

Maddox, the principal, said Elkin would welcome all the extra help and resources it could get to beat back the collateral effects of opioid addiction that wash onto school property like a tide each morning.

“It’s not over,” she said of the neighborhood’s drug crisis. “I want to make that clear to everyone, that it’s not over.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.