Gamblers, foreign money and struggling homeowners: Inside Philly’s sheriff sale boom

Above a nondescript dry cleaners in Center City sits a mysterious little office. The rare visitor has to walk through an unrelated tax preparation business to reach its three tiny rooms, each overflowing with stacks of paperwork. No signs mark the office, let alone one that would indicate that it’s home to Philadelphia’s biggest sheriff sale buyer, and, therefore, one of the city’s biggest landholders.

In just the past three years, Adam Ehrlich has used this shoebox to pick up least 492 tax-delinquent properties at sheriff sale – semi-weekly, government-run auctions of land in arrears for tax or mortgage payments.

A PlanPhilly analysis of city deed records estimates that the one-time professional poker player-turned-real estate mogul has spent about $2 million to acquire the equivalent of roughly 11 square blocks’ worth of land. The true extent of Ehrlich’s empire is unknown as he has used a constellation of 49 separate holding companies linked to his downtown offices – a legal shield against possible lawsuits.

“It is my understanding that I am the biggest purchaser” of sheriff sale properties, he said in a July phone interview, although he declined to discuss specific numbers.

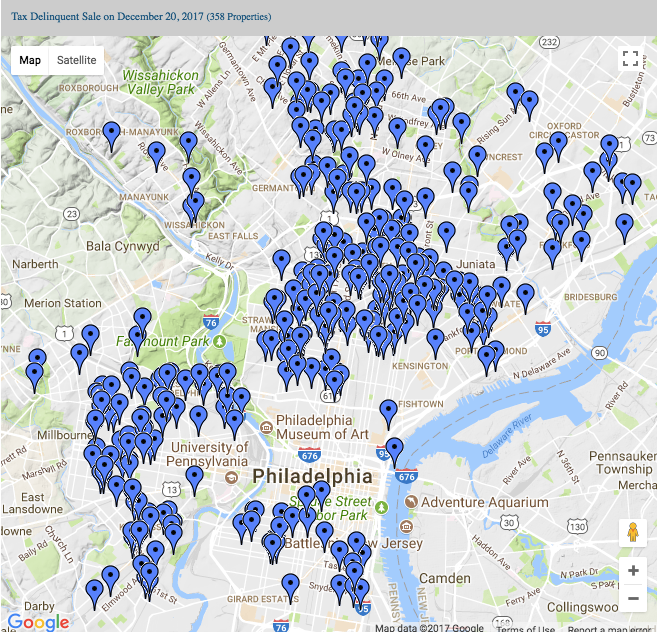

Ehrlich is a new kind of buyer, one emblematic of the city’s booming real estate market. Once sleepy sheriff’s auctions have become crowded with bidders hoping to cash in on skyrocketing real estate prices. The city is also sending more tax-delinquent land to auction than ever – although not all made it to sale, tax lien foreclosure petitions jumped from 7,600 in 2013 to 10,680 last year.

It’s a trend that has drawn the ire of political figures like City Council President Darrell Clarke, who say many buyers are mere speculators hoping to catch the next gentrification-fueled boom. Legal advocates who represent indigent homeowners say the increased pace of sales sometimes threatens homeowners with eviction over minor tax bills.

Ehrlich admits his purchases are nearly all are in the city’s most poverty-stricken neighborhoods, although he strongly emphasized that he has never bought an occupied property – not worth the trouble, he says. He argues that sheriff sale buyers provide a valuable service: putting delinquent properties back onto city tax rolls.

“These tax-delinquent properties would go by auctions with no one bidding on them, [with] no money collected by the city. The city even sold a bunch of their old liens to a bank once,” Ehrlich said.

But newcomers to real estate, like Ehrlich, may also have little expertise in property management, struggling to keep up with maintenance as their holdings rapidly grow. In July, the Department of Licenses & Inspections said it was tracking open code violations on 305 properties controlled by Ehrlich for issues ranging from missing permits to serious structural safety hazards. The city has sent some of Ehrlich’s holding companies to court over outstanding code violations and tax liens.

BET THE HOUSE

In a phone call following a PlanPhilly reporter’s visit to his office, the 42-year-old Ehrlich declined to discuss exactly how he came into the wholesaling business. He said only that “a friend” told him he had “the right skills,” but declined to say what skills those were.

Ehrlich’s LinkedIn profile lists a background in options trading, although he appears to have restyled himself as a professional gambler and women’s jewelry wholesaler sometime in the late 2000s. Going by the self-anointed nickname “Good Bet” in tournaments (“Because I’m a damn Good Bet”), he won a spot on NBC’s “Face the Ace” in 2009.

With a shock of curly hair and a shiny crimson button-up, Ehrlich would become known to viewers for his talkative-but-aloof nature in the televised quest for a million-dollar poker prize. He would ultimately lose everything on a $200,000 match-up, standing beside host Steve Schirripa, an actor best known for playing Bobby Baccalieri on The Sopranos.

In 2012, Ehrlich resurfaced as a predictive analyst betting in the world of political odds markets, and was quoted in a Bloomberg Businessweek article gaming out the results of that year’s Republican primary in Iowa. Rick Santorum’s narrow win bucked analysts that had leaned heavily towards candidate Mitt Romney.

Today, Ehrlich seems to be hedging his bets, so to speak.

He describes himself as a “property wholesaler,” a niche business term often used in areas with lots of distressed real estate. Wholesalers turn a profit, in part, by acting as a middleman, extracting a premium from developers leery of buying directly from government auctions that are too risky for guarantees like title insurance.

But while most wholesalers make money by snapping up and cleaning the most readily salable properties at auction, Ehrlich has taken the opposite approach.

“I focus on the properties that are in the worst condition, and vacant lots,” Ehrlich said, while admitting he has little interest in developing his land. “I don’t have the background in terms of construction experience. Everyone can do it quicker or cheaper… But there’s more to life than building new construction.

“There’s some properties that have 20 years of back taxes on them. Or maybe there are old water bills or issues with the title. The amount of liabilities make it so nothing can be done with a property,” Ehrlich added. “I do my best to clean all the encumbrances.”

Ehrlich handles these obstacles en masse, hauling stacks of paperwork to the Municipal Services Building for marathon mediation sessions with the city’s bureaucrats. He similarly appeals the tax assessments on virtually every property he owns, in a bid to reduce carrying costs; Ehrlich says his numerous tax appeals account for the millions in back real estate taxes the city lists across his properties.

Finally, properties are listed for resale on a variety of websites he operates, usually for a few times what he paid at auction. Unusually, Ehrlich allows buyers to purchase his properties in untraceable cryptocurrencies like BitCoin or LiteCoin.

In general, he describes his new business in gracious terms, fondly recalling a lot he gave to the Philadelphia Fletchers Club (colloquially called “urban cowboys”) for $100 to use as a stable. Sheriff Jewell Williams, who offers classes on bidding at sheriff sales and has trumpeted the increasing number of successful auctions during his tenure, gave him a good citizenship award for the gesture.

“I’m not 100-percent, solely altruistic. But you can be altruistic and make money at the same time,” Ehrlich said. “I’m making these properties available to the flurry of contractors and first-time homeowners that are out there looking for land and may not know how to deal with the sheriff sale process.”

Real estate analysts said there is something to Ehrlich’s notion that he and similar buyers are investors, rather than speculators, due to the immense bureaucracy associated with city land sales.

“It’s a grey area. To call him a pure speculator isn’t accurate because he’s adding value of some sort,” said Drexel University economist Kevin Gillen. “It makes the land more attractive to developers. It increases the value of the land by about 15 percent.”

While he recoils from the term ‘speculator,’ Erlich’s language sometimes calls that label to mind.

“Brewerytown, no one used to want to touch it at all,” Ehrlich said, describing a low-income neighborhood that recently boomed. “I think Mantua is the next area. It had the highest per capita murder rate in the city, but it’s a stone’s throw away from downtown.”

It’s hard to see how the investor could make money without relying on some long-term speculation. The pace of Erhlich’s acquisitions far exceeds the pace of arms-length sales: City deed records show just 72 of the nearly 500 plots tracked by PlanPhilly appear to have sold.

Asked about these buyers, Ehrlich said a lot of the properties he’s sold have wound up as side yards or parking lots: Much of his land is far too devalued to attract new development.

He’s even made a sport out of thinking up corny names for his numerous holding companies that riff off the distressed nature of the vacant land he’s purchased, like “Lots and Found LLC” or “LOL LLC.”

“Everyone always says the corporate names aren’t particularly important, but I just like names with a double entendre,” Ehrlich says. “I had one that was called ‘Propped Up LLC,’ and most of the properties were falling down. So, they were actually propped up. But they’re also properties.”

Cashing In

Whatever Ehrlich’s motives, it’s a point of pride that he’s gotten to the top of a booming auction market without kicking anyone out of his or her home. But he freely acknowledges that not all his fellow bidders at city auctions share this buying philosophy.

“I don’t want to put grandma out on the curb. I’ve never had to evict a single person,” he said. “But I see so many other people act in a predatory manner.”

Inside West Philadelphia’s sprawling First District Plaza, a church-owned building that typically hosts four or five sheriff sales a month, would-be purchasers gather inside something resembling a conference room at a two-star hotel. All sales are in cash, effectively sight unseen, and final.

“This property was deemed imminently dangerous. Can I get nine thousand?” drones a sheriff’s deputy onstage at a recent sale.

Buyers hunch over catalogues, printed by a private company and sold for $10 dollars-a-pop, detailing the properties on the block that day. It’s a motley crew: some men are in polos emblazoned with real estate company logos; others are in Hawaiian t-shirts and flip-flops. There are mother-daughter or father-son teams; a few would-be bidders who look no older than 21. Some are pros, but many are amateurs, lured by the promise of cheap real estate.

James Donnelly is one veteran buyer. He’s been coming to sales here for nearly 17 years. In that time, Donnelly estimates he’s bid on “hundreds” of properties, although he’s only won about a half dozen.

“There’s a lot of risk there,” he says of the auctions. “The properties are locked up by the sheriff and you can’t get inside. You could double your money or lose it all because you bought a property where all the joists are rotten.”

Donnelly says he uses satellite images on Google Maps to scout the condition of roofs or overgrown backyards as properties come up for sale – signs of distress. He says the most sophisticated buyers will visit homes in person.

“I wouldn’t say it’s high reward. But it’s a good reward if you do your research … You might get a property for a 10 or 20 percent discount,” he says. “But next week the city [could be] coming to tear that building down. And now you own an empty lot, and you might have to pay back the demo costs.”

Sometimes, properties are still occupied. Owners have the right to buy-back their property within nine months by paying the purchase price at sale, plus interest and certain costs.* Known as “right of redemption,” it’s a hazard for buyers like Donnelly – albeit an unlikely one.

“If their property is going up for sale, it’s usually an indication they’re not having a good time with their finances. So, the likelihood of them coming back is low,” he says. “But maybe it’s the home they grew up in and they just won the lottery. Who knows?”

Donnelly described himself as a bit of an anomaly: Unlike investors like Ehrlich, he rehabs the few properties he wins.

“Professional developers tend to buy things through ordinary means — a realtor. Most of the pros at sheriff sale are really speculators. And I think pros buy about 75 percent of the properties, maybe higher,” he says. “They have a longer range outlook. They’re not fixing them up. They’re holding onto them for capital gain or to sell to another individual.”

In Donnelly’s years at sheriff auctions, he’s watched the Philadelphia market get progressively more competitive. When he started attending sales, First District Plaza was mostly empty. Now, investors pack the conference room.

The growing interest is the product of, and maybe a contributing factor to, Philadelphia’s strengthening residential real estate market. Housing prices in the city have appreciated 19.3 percent in the last ten years, compared to just 9 percent nationally, according to data compiled by Drexel’s Gillen.

As the city’s real estate market has heated up, it’s drawn attention, and money, from well beyond the region. Donnelly described the frustration of going up against more and more bidders backed by seemingly limitless international investment dollars – a trend that is hardly unique to Philadelphia.

“There’s a lot of foreign money that comes into the market. They’re bringing money in from countries where they feel it is not secure,” he says. “There are agents who have done the research and they will buy almost anything. Many also go to sales in Allentown or Upper Darby [too] — they buy in the whole region. You’re up against pros with seemingly unlimited capital resources.”

Reph Chorew, a local realtor, agreed that the cash-only nature of the local sales was particularly appealing to foreign investors.

“You’re buying in cash and selling it to a developer in cash. It’s a cash-to-cash purchase. When you start dealing with banks as a foreign investor, you have more hoops to jump through. This is easy in and easy out.”

At the end of the day’s first auction, a group of men smoke cigarettes outside on Market Street. These are the self-described “pros” – sheriff’s sale regulars with LLCs and connections to foreign money, many with ties to Eastern European countries. They say they are proud of their business; none were willing to provide their full names.

A man, who asks to be called Steve, says the research and bureaucratic hassles attract a distinct type of repeat buyer to city land sales.

“Sure, it’s speculative, it’s speculative. It’s gambling,” he says. “But these guys,” Steve points to his associates, “they’re all workaholics. They’re just trying to feed their families.”

Another man interjects. He does not identify himself, but bemoans the work of a sheriff sale purchaser, describing it as a “crazy” business.

“One crazy woman calls me at 11:40 at night. I hang up three times, and she keeps calling back, crying,” he recalls. “She wants her house back. She doesn’t understand: The city sold her house.”

So why bother with the hassle?

“The U.S. is one of few countries where you can make money on real estate. You can make a corporation and then you own something,” says a Ukrainian man, who asks to be called Sasha. “Sometimes, people will drive down from New York City just for these sales.”

They’re a tight knit group, the professionals say. So, of course, they all know Adam Ehrlich – who one even refers to by his sobriquet, “Good Bet.”

Sasha, who says he comes to every auction, can’t remember how many properties he’s bought anymore. But he knows Ehrlich has purchased far more.

“There are maybe seven or eight groups of guys who do this as a business. Everyone else doesn’t know what they’re doing,” explains Sasha. “Adam, he buys a lot of shit. But what can you say? Everyone here has their own idea of how to invest.”

GOING BUST

The scandal-plagued Sheriff’s Office had long been criticized over the slow pace of its delinquent land sales in a city with tens of thousands of them. From the buyers’ perspective, the flood of new properties being sent to auction is helping investors turn a profit, while the city collects on past debts – everyone wins.

“I think the city could still increase the pace of sales, honestly,” Donnelly says.

(The Sheriff’s Office declined to comment for this story. Williams has kept a low profile since the Philadelphia Inquirer reported on sexual harassment lawsuits filed against him.)

But as the city has grown exponentially more aggressive in pursuing tax sales, some struggling homeowners say they’re caught in the middle, sometimes over marginal amounts of back tax. The “predatory buyers” Ehrlich described don’t care if a property is inhabited or not.

James Murphy’s home has been threatened with sheriff’s sale three times over just $1,073 in back taxes. The homeowner has been locked in a dispute with the city over the balance since 2014 – the first and only year he’s ever missed a payment on the house he’s owned for 20 years.

Murphy swears he paid and filed an in-person dispute with the Revenue Department. The city insists he owes – and that he missed a string hearings before they sent his home was sent to auction in 2017. With investors appearing on his lawn to photograph his home, Murphy applied to enter into a payment plan to forestall the sale. Ultimately, the city would schedule, then postpone, auctions of Murphy’s home three times before lawyers from nonprofit law firm Community Legal Services helped him arrange installment payments for his debt.

From the city’s perspective, this story has a happy ending.

“This illustrates all the efforts the city takes to prevent a sheriff sale and how hard both the city and its outside counsel work to give homeowners every opportunity to become compliant,” said city spokesperson Mike Dunn. “Three sheriff sales were scheduled, but the sale was postponed all three times.”

The former housing inspector, who was forced into early retirement by pancreatic cancer during this back-and-forth with the city, says that’s all besides the point.

“The city was strong-arming me. There was nothing I could do. I could have lost my house,” he recalls. “It’s a strain on you because I’m already looking at how I’m going to pay any bills this month or next month while our salary is cut in half.”

CLS lawyer Jon Sgro said the city’s focus on homeowners with small tax debts is especially unfortunate because most citywide tax delinquency – 60 percent – is linked to investors or landlords.

“The Murphys almost lost a home valued at $107,000 over a $1,100 tax debt,” says CLS lawyer Jon Sgro. “Their case exemplifies the city’s aggressive, one-size-fits-all approach to tax foreclosures.”

For the Murphys house to be put up for auction within a couple years is also striking. Nearly 73 percent of tax-delinquent properties have been outstanding for anywhere from 3 to 35 years, according to a 2012 analysis of 107,000 delinquent properties.

The Murphys are also hardly alone. While it’s worth noting that the city does not track owner occupancy in a meaningful way, Council President Darrell Clarke’s office has estimated that around 4,500 owner-occupied properties were petitioned for tax sale last year.

Many, like the Murphys’, may never have made it to sale. But Sgro said the city should stop sending owner-occupied properties to sale altogether – or at least limit the threat of foreclosures to the absolute worst offenders.

He argued that these “near miss” cases waste the time and resources for nonprofits like CLS and risk exacerbating a citywide housing affordability crisis. As 30 percent of CLS’ $10 million budget comes from the municipality, the city is picking up a small part of the tab to resolve its own tax foreclosure cases.

“In our view, it makes little sense as a public policy to seek to sell the property of a family that paid their taxes faithfully with the exception of one year,” he said, referring to the Murphys’ case.

In the fall, City Council passed legislation to create a tax foreclosure diversion program for low-income homeowners. The bill, introduced by Clarke, is an indirect response to the city’s aggressive pursuit of delinquent taxes.

“All of our city’s policies should be centered on basic human dignity,” said Clarke’s spokesperson, Jane Roh. “Leaning on sheriff sale with the single-minded goal of collecting revenue, with no regard for the circumstances that led to a homeowner’s delinquency, is counter to that overarching goal.”

Mayoral spokesman Mike Dunn said the city, for its part, is piloting a “Trauma-Informed Customer Service Training” program to better equip its staff to handle 700,000 phone calls and 130,000 walk-ins the department hears from each year, many over property tax bills.

“Odds are many of our taxpayers and water customers, like 4 out of 5 Philadelphians, have suffered from or been exposed to trauma,” Dunn said. “We want staff to be equipped to provide high-quality, compassionate service in all situations.”

But to James’ wife, Teri-Lynn Murphy, her tax woes were the source of her family’s trauma. The time she spent navigating city bureaucracy when she had precious little to give as she cared for two teenage children, aging relatives and, eventually, her own sick husband. The humiliation of having her family’s financial stress made public when her home was marked for auction.

”It’s just a lot to deal with. Your neighbors are always saying, ‘What’s going on? You guys moving?’” she tearfully recalls. “If it’s happened to us, I can imagine other people going through the same thing. It’s not right.”

*CORRECTION: This sentence original read “Former residents have 90 days to win back their properties if they pay off associated debts and fees.” While that is true in most instances, there are a few other options sometimes available to former residents to let them reclaim their properties after nine months.

Hi there, read PlanPhilly often? The news that you read today is only possible because of your support. Please help protect PlanPhilly’s independent, unbiased existence by making a tax-deductible donation during our once-a-year membership drive. We cannot emphasize enough: we depend on you. Thank you for making us your go-to source for news on the built environment eleven years and counting.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.