From Bucknell to the big time: Three days with an NFL draft prospect

ListenWhile the masses partied on the parkway, we watched and waited with Julién Davenport, star offensive tackle and NFL hopeful.

It’s hard to tell if Julién Davenport is more David or Goliath.

The Goliath part is pretty obvious.

Davenport, an offensive tackle at Bucknell University in Central Pennsylvania, is biblically big. At 6 foot 7 inches and 318 pounds, Davenport is a large man in a world of large men.

“I don’t look up to many people,” said his college coach, Joe Susan. “He’s one of the guys, as soon as you meet him, you’ll say he’s a little bit taller than I thought he’d be.”

Then there’s the David side of Davenport — a kid so unassuming and overlooked most people don’t know how to spell, or say, his name.

The first time we meet, Davenport tells me his first name is pronounced Julie-own, with a French inflection on the second syllable. In the three days I spend with him. every single person we meet calls him Juli-en, the way you’d pronounce “Julian.” He never once corrects anybody.

Same goes for the spelling.

Someone at some point decided Julién should be spelled Julie’n. Davenport doesn’t know who or why. You’ll find this spelling all over the internet, even on Bucknell’s official website. Again, he plans no corrections.

“I didn’t make it a big deal,” Davenport said “Just let it ride. [I] thought maybe their software couldn’t put the accent mark over the e.”

Even if people did spell Julién correctly, Davenport wouldn’t be a household name. Bucknell is a small school in a small conference, known more for its academic excellence than its football prowess. The Bison haven’t had a player drafted into the NFL since 1969. It’ll be on Davenport — the big man from the little school — to break that streak.

WEDNESDAY

On the Wednesday before the NFL draft, Davenport wakes early to finish two term papers — one on the Patriot Act and another on mass incarceration. Around 11a.m. he criss-crosses Bucknell’s campus in Lewisburg, Pa., to the sound of church bells, prints out a copy of his paper on the Patriot Act, and hand-delivers it to a political science professor.

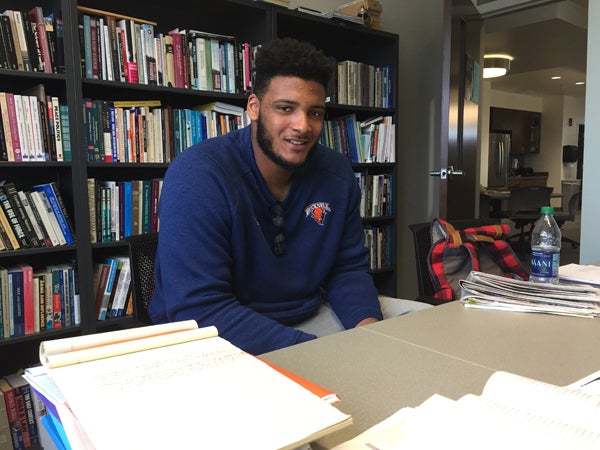

Julién Davenport (Avi Wolfman-Arent/WHYY)

Julién Davenport (Avi Wolfman-Arent/WHYY)

It is a strikingly familiar college sequence — almost tender in its normalcy. Today he is a senior with 286 Twitter followers and an endearing penchant for nodding hello to just about everyone who passes him on campus.

But things are about to change for Davenport. On Friday night, he will gather with friends and family at his dad’s house in Blackwood, New Jersey, to watch the second and third rounds of the NFL draft. Davenport never expected to be picked in the first round — and he wasn’t. So his hopes are on Friday. If he isn’t taken then, the assembled will hold their breath and watch again Saturday for the final four rounds.

“Everybody asks me this all the time, ‘Hey, are you nervous and all?'” he said. “And it’s just my nature, I would say, I just get more anxious than nervous.”

He says there’s a difference. Nervous means you’re dreading what might happen. Anxious means you’re looking forward to it.

Davenport was born in Camden. His dad, Anthony Davenport, is a former Marine who spent 24 years on the Camden police force before retiring to a job as a high school security guard. His mom, Leslie Showell, teaches at a public elementary school in the city.

When he was about 7, he and his mom moved from Camden to Paulsboro, a small, working-class town about 12 miles south along the Delaware River. Shortly after the move, Showell’s kitchen sink backed up.

A single mom and new homeowner, she first called the police — who then referred her to the borough. A town employee came out to fix the plumbing and quickly forgot why he’d arrived.

“I was definitely pretty big — so [that] definitely opened his eyes,” Davenport said. “Made him forget about the plumbing and ask about my age.”

The maintenance man, it turned out, was a youth sports coach. He told Showell he’d be return in the summer to sign her son up for football. Besides, the clogged pipes weren’t on borough property, so there was nothing he could do. Showell called Roto-Rooter, and her son eventually signed up for football.

Despite his athletic prowess, Davenport’s default state is silence. His laugh is quick and contained.

He sidesteps most of the usual questions one asks an NFL prospect. He swears he isn’t going to splurge on anything with his first NFL pay check. He’s already got his dad’s 2007 Dodge Charger, and it runs fine.

He once told his older brother, EJ, that he’d treat himself to a 20-piece chicken McNuggets after inking that first deal. Davenport swears it was a joke.

FRIDAY

Friday starts with a quintessentially suburban scene: A muggy afternoon. A dad out by his shed. The crack of a hammer set against the yapping of neighborhood dogs.

After 10 hours preparing the backyard for what could be the biggest night of his son’s life, Anthony Davenport nails in the final touch. It’s a poster with pictures of Julién layered under two images: One the logo for Bucknell University, the other an NFL shield.

Across the bottom is his name in bold, blue letters: “Julie’n Davenport.”

Around front, Julién’s mom unloads a car stuffed with cases of soda and bottled water.

“You should have seen us at the grocery store trying to push the cart,” she said. “The water was actually two cases for $5. Normally it’s three for $10. It was two for $5.”

A mom talking about a supermarket bargain. A dad out by the shed. You could’ve commissioned a Rockwell painting.

(Avi Wolfman-Arent/WHYY)

(Avi Wolfman-Arent/WHYY)

The focal point of the watch party is a large projector screen Davenport’s dad set up in the backyard.

A large rental tent guards against the unlikely prospect of rain. Wedged near the perimeter, a pair of picnic tables contain a seemingly limitless supply of barbecue.

The second round begins with a pick by the Green Bay Packers. Julién settles into a wicker chair near the television, moving only rarely, an iPhone 7 cradled in his massive left hand. Occasionally he lifts the phone to scroll through social media. When little cousins bounce by, he dispenses high fives. Otherwise he is still.

Two types of parties swirl around him.

There are those whose eyes rarely leave the television, like Julién’s stepmom, Tonya Davenport. Tonya and a few others track every pick. Since Julién is an offensive tackle, they’re waiting for other offensive tackles to be drafted so that the supply of available players diminishes.

When Cam Robinson, an offensive tackle out of Alabama, goes early in the second round, she gives a little whup.

“We’ve been waiting for him to go,” she said. “We need him to get off the board. Get out the way.”

Julién’s agent, Ed Wasielewski, keeps a little cheat sheet rolled up in his hand. It lists every draft slot, with orange highlighter to mark the teams that either showed interest in Julién or need offensive linemen.

He and Julién steal quick glances throughout the night, but he largely remains calm and out of the way. At one point in the third round, New England takes an offensive lineman out of Troy, and Wasielewski pumps his fist. His client should be one of the next couple offensive tackles off the board.

Then there are those who either can’t bear to watch the draft unfold or don’t have the requisite, four-hour attention span.

In the kitchen, Mattie Mallory, Julién’s stepgrandma, entertains the drifters by dispensing shots of moonshine mixed with lemonade and good humor. She never takes a sip.

“I’ve got 25 miles to drive tonight,” Mallory explained.

Besides, she’s got a jar at home.

The iPhone in Julién’s hand doesn’t ring. The weather chills, along with the mood. Julién Davenport will not be picked tonight.

There are no tears or obvious displays of disappointment as the party breaks up.

A few of Davenport’s teammates gather without him for a round of shots.

“To the league,” they toast.

As the party-goers say their goodbyes and disappear into the night, a flock of teenagers sneak from one nearby house to another. The dogs are still barking. The televisions go quiet. Back to suburbia.

SATURDAY

When I arrive Saturday, I spot Anthony Davenport, Julién’s dad, seated in his driveway. He offers up a Corona and starts scrolling through his phone.

As he scans through the draft order he whispers team names to himself.

“Arizona, Cincinnati, Chicago, Eagles …”

“… the Colts always need linemen …”

“… they picked a tackle in the first round … I think …”

“… Houston at 130 …”

A phone call Friday would have been nice. A phone call today is an absolute must. The longer it takes to be drafted, the less likely it is Julién will make an NFL roster. Plus, rookie salaries are almost wholly determined by draft position.

A player drafted at the top of the fourth round can expect a signing bonus of around $700,000, according to the website spotrac. That’s money the player will receive even if he never plays a down of professional football. A player drafted at the end of the seventh round will get around $65,000. It is the difference between a life-changing pay out and the salary of your average nurse. And that’s before considering how much more likely it is that a player drafted atop the fourth round collecs several years of NFL paychecks.

The mood on Saturday reflects the stakes. Stepmom Tonya busies herself in the kitchen to wall off stress.

“It’s definitely tough,” she said as she sprays cooking oil on a sheet pan full of raw chicken. “And you’re processing and you’re worried. Yep! That’s why I keep cooking.”

Julién arrives late.

On the way, he video chats a group of friends. His mom, Leslie Showell, notices he’s wearing the same shirt as yesterday and begins a frantic search for something that’ll fit him. She turns up an orange polo shirt — crisis averted.

When Julién does arrive, a few picks into the fourth round, he seems restless.

Instead of parking near the big projection screen like he did Friday, Julién moves from room to room, as if trying to avoid the crowds that inevitably tail him. The tension builds for about an hour.

Shortly after 1 p.m, Anthony Davenport — normally as stolid as his son — bounds out the back door.

“He got a call!”

Showell, seated in the wicker chair Julién inhabited for most of the prior night, shoots up.

“He got a call?”

From every corner of the house people converge on a big-screen television just off the kitchen.

“Houston? Is it Houston,” one of his college teammates asks.

Prospects don’t find out if they’ve been drafted by watching television. Rather, the team calls the player and his agent shortly beforehand to deliver the news. To the agent, they’ll ask if the player has been injured or arrested in the last couple weeks. To the player, they say congratulations.

By the time the pick is set to be announced on television, about 40 people are packed around the television. The pick comes from retired astronaut Scott Kelly, stationed at Space Center Houston and flanked by a quartet of cheerleaders.

“With 130th pick in the 2017 NFL draft, the Houston Texans select Julién Dav…”*

Before Kelly can finish the room erupts. Julién’s mom and stepmom wrap him in hugs from either side. Julién barely moves.

When Julién got the call, he was by himself, in the back corner of the basement, as far as one could be from the party and still be on the property.

Seated before perhaps the smallest television in a house full of massive screens, he played the video game Overwatch on XBox360 and enjoyed a precious moment of distraction and solitude.

(Avi Wolfman-Arent/WHYY)

(Avi Wolfman-Arent/WHYY)

When his phone rang, he first thought it was a friend trying to find him. He ignored it because in that moment he didn’t want to be found.

“I look, and it’s a Houston, Texas, number,” he recalls.

You assume going into an event like the NFL draft what the high notes will look and sound like. But fate has a way of finding the unexpectant, like water running to a drain.

Julién Davenport (Avi Wolfman-Arent/WHYY)

Julién Davenport (Avi Wolfman-Arent/WHYY)

Looking back … and looking up

For Leslie Showell, that unguarded moment arrived the Monday before the draft while she drove to her job in Camden. As she barreled up Route 42, she switched off a profanity-laced pop song and turned on a Pandora station set to gospel music.

Without warning, she began to cry.

Recently she’d come across some old pay stubs, relics of tougher times. During one of her pregnancies, high blood pressure had forced her to drop out of college. It took her eight years to get an associate’s degree.

In those days she’d worked as a teacher’s assistant and a school bus driver.

“I don’t know how I survived off $896 every two weeks,” she said. “I mean, I had a little bit of child support, but still.”

She thought about her four children — beautiful and healthy — children she’d helped raise as a single mom.

“That ride wasn’t easy, but we survived,” Showell said.

Now, on this ride to work, the tears streamed down her face.

The song was an old hymn titled “His Eye Is On The Sparrow.” The gist of the song is that God sees everything, even the smallest bird.

“And I know, I know he watches over me,” it ends.

If God can watch the sparrow, surely he can look after Davids and Goliaths alike. And surely he can look after Julién Davenport, offensive lineman for the Houston Texans.

*For those curious, players picked in the middle of the fourth round are likely to make an NFL roster, but are no sure bet to stick around long-term. With the 130th pick in the 2005 draft, the San Diego Chargers selected Darren Sproles, a prominent running back and punt returner who still plays professionally. Seven years later, the Baltimore Ravens spent the 130th pick on Christian Thompson, a safety who played one NFL season before a suspension ended his career.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.