First year, first generation: Going home

Listen

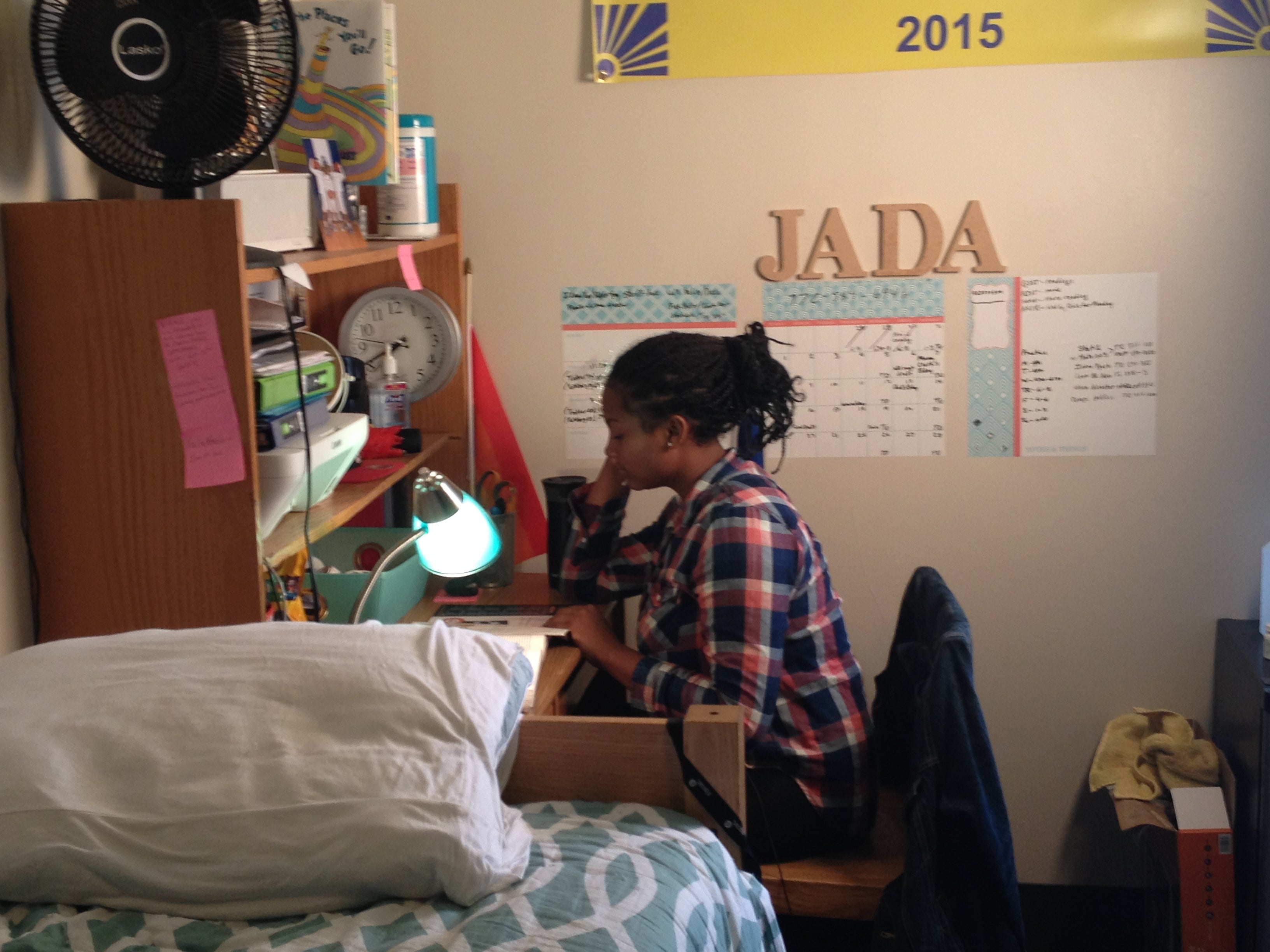

Swarthmore student Jada Smack studies in her dorm room. (Avi Wolfman-Arent, NewsWorks/WHYY)

Many freshmen see college as a first foray into indepdence. So why are the students in our first-generation project so keen on going home?

This is the fourth story in our First Year, First Generation series. For an introduction, click here.

You can listen to Part 2, Part 3, Part 5, and Part 6 by clicking on the links.

Since early summer, I’ve been following five first-generation, first-year college students from Delaware as they transition to higher education.

A month or so into the first semester, I noticed a trend. When I’d ask the students about their social lives they’d often mention–somewhat casually–that they were spending weekends at home. And it wasn’t like they were going home occasionally for some specific purpose. Rather, it was habit. When Friday hit they were making the trek home, or at least trying to score a ride there.

Each had different reasons for these return visits.

Sean Ryan, a freshman at the University of Delaware, went home to see his girlfriend and eat Sunday dinners with his mom. Jacki White, also at UD, relished the opportunity to do laundry for free. Jada Smack, a Swarthmore student, wanted to honor family obligations. Cierra Jefferson, a frosh at Wesley College, had a weekend job that took her in the direction of home.

Clearly, though, there was some common appeal to spending weekends off campus.

“I’m just really, really excited to go home after a long week of school and long week of studying–just a sense of a break of not being on campus or not being in the dorms,” said Cierra Jefferson one Friday night as she fired up her car and headed south toward her home in rural Delaware.

Frankly, I was surprised. I expected some homesickness, sure. But I also imagined weekends spent testing the party scene or going to campus events. Part of the reward for making it to college is that you have a hyperkinetic social scene at your doorstep. Not all of it will appeal, but your first months on campus should be about finding which parts of it you enjoy and which you’d rather avoid. The social scene is this canvas on which you get to express your newfound independence. At least that’s what I thought.

And the fact that I–a child of the middle-class with two parents who graduated college–saw college this way is no surprise.

Middle-class students view college as a place where, “they will finally be able to separate and distinguish themselves from their parents and…realize their individual potential,” according to a 2012 study by a group of five researchers. College administrators share this vision. When surveyed, the folks who run colleges say that the undergraduate years are all about finding yourself.

That same study, though, found that working-class and first-generation students had a different take on higher ed.

“When we ask them about their motives for attending colleges these tend to be more interdependent motives. I’m here to bring honor to my family. I’m here to help my community,” says Rebecca Covarrubias, an assistant professor of psychology at the University of California, Santa Cruz and one of the study’s co-authors.

Covarrubias has also written on the phenomenon of family achievement guilt: the notion that first-generation students often feel guilty for surpassing their parents academically. It’s a parallel idea to survivor’s guilt, except in this case students don’t wonder why they lived, but rather why they have these great educational opportunities while others back home are just getting by.

Taken together, Covarrubias’ work points to the idea that first-generation students often have a different and, perhaps closer, relationship to home life than their independence-seeking, middle-class peers.

A little over a month ago, I decided to run all these ideas by Jada Smack, the Swarthmore student.

Jada is from rural, Southern Delaware, and when we first met back in May, Jada talked excitedly about leaving her small hometown and venturing out into the world.

“I don’t really think I’m gonna be able to reach my full potential just staying in Millsboro,” she said. “And there’s nothing wrong with Millsboro. But I don’t wanna be a farmer and I don’t wanna be a nurse. So I don’t really see how I can expand out to all the possibilities of my life. I don’t want to shelter myself and make myself confined to just this one area and not be able to do everything that’s possible for me to do.”

Jada made the two-hour journey back to Millsboro twice during the first five weeks of school. She tried to go back on two other occasions, but her ride fell through. Of all the students, Jada’s trips home surprised me most because she seemed the most eager to break away.

She explained it like this: Swarthmore’s great, but it’s overwhelming.

“It’s not a bad place to be, but you can kind of get tired of it really quickly,” Jada said of Swarthmore. “I can get tired here much more quickly than I get tired being at home.”

Jada talked about how little things–like a conversation between students about politics–could make her feel unworldly or even unworthy. It was hard to adjust to a world where not knowing the various waves of feminism excluded her from participating in casual banter.

Plus, going home, allowed her to reconnect with family–something she clearly prioritized.

“I’ve seen people leave and go to college and do all these great things for themselves and forget who they are and forget where they came from,” said Jada. “I just wanna go back and remind my family that’s never gonna be me.”

When I brought up the idea of family achievement guilt with Jada, she stopped me and asked if she could guess what it meant. She nailed the definition within five second of hearing the phrase.

I asked if she could relate to the concept, and she nodded yes.

“I don’t feel guilty for going to college, but I feel kinda guilty for leaving when I need to maintain a relationship with my family,” she said.

Cierra Jefferson, the student at Wesley College, also has an uneasy relationship with her newfound independence. Family matters a lot to her, and so far she’s made the one-hour trip home every single weekend.

“Yeah I am very homesick,” she told me. “I’m not that far away, but I don’t know what I would do if I was any further.”

Cierra has attempted to find a social niche at Wesley, but it’s been slow going. She tried out for, and made, the school’s step team, but quit soon after due to a work conflict. She’s thinking about joining a sorority, but worries about the time commitment.

These may seem like minor setbacks, especially since Cierra has thrived in the classroom. But there’s considerable research showing that campus engagement improves student retention. The benefit is even greater for first-generation students because campus networks allow them to build the social capital they often lack. Problem is, first-gen students are less likely to get involved in the first place.

Cierra is already thinking about commuting from home next semester or even transferring next year. Even as she slowly adjusts to college life, the pull between her old home and her new one remains.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.