How Philly gamblers helped raise $500K toward a fresh horse barn for kids in Fairmount Park

A $15 million indoor polo arena and renovated horse barn is coming to a corner of the Fairmount Park forest.

From Philly and the Pa. suburbs to South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

When gamblers are placing their bets this holiday season across Philadelphia casinos, they may not realize that a portion of gaming revenue is shared with nonprofits which then support public interest projects.

But that’s what the Pennsylvania Race Horse Development and Gaming Act, commonly known as the Pennsylvania Gaming Act that was signed into law two decades ago, requires.

Each legal gaming operation within county limits across Pennsylvania — which in the case of Philadelphia is also within the city’s boundaries — sends a share of its revenue to the state, which then reallocates the money as grants.

The local share for Philadelphia was $6 million this year, according to the Pennsylvania Department of Community and Economic Development.

Inside that figure, a local youth horseback riding and polo game training nonprofit, Work to Ride, was awarded a $500,000 grant in late December.

This grant helps ensure Philadelphia teenagers like Tajee McLaughlin have a place to go after school and on the weekends that’s safe and fun.

It also means that the program can expand, reach more youth and operate year-round on a remote hill in Fairmount Park with a view of Center City Philadelphia that’s accessible by public transportation.

Not just horse play

Just before 9 a.m. on a chilly Saturday morning in mid-December, the 15-year-old West Philly native was mucking his horse Pistachio’s stall in below freezing temperatures. He shared his experiences riding Pistachio so far.

“He’s a wild card. He’ll take off [galloping] when he wants to. He won’t necessarily buck you off but if you’re not paying attention he’ll get you off [his back],” McLaughlin said. “He’s a white pony but colored with fleabitten [grey-flecked] spots. He’s not chubby but I’d say fit for his size.”

Pistachio is a horse, but referred to as a pony because he is trained to play horse polo, an elite game with leagues open to high school and college students nationwide.

McLaughlin was working inside a temporary barn near Chestnut Hill College in Northwest Philly as the 36 horses who usually live in the Fairmount Park barn — known as the Chamounix Equestrian Center — were scattered across several states during renovations that began in October.

But by next winter, McLaughlin and dozens more youth can expect to groom and care for horses in a freshly renovated, unnamed barn equipped with an indoor arena that will be named the McCausland Arena.

Overall, it’s a multmillion-dollar project underway for Work to Ride, founded three decades ago by local horse trainer Lezlie Hiner.

Hiner said that the project is a huge leap forward for the organization that accepts retired racehorses as donations who are trained into polo horses for Philadelphia youth to ride.

“Oh my goodness. It’s going to mean the world. Right now, the kids are riding at night after school. It’s dark, the ground is frozen. They’re cold,” she said. “So this will really allow us the opportunity to be more consistent with the kids and with their programming.”

Barn cats, horses and kids

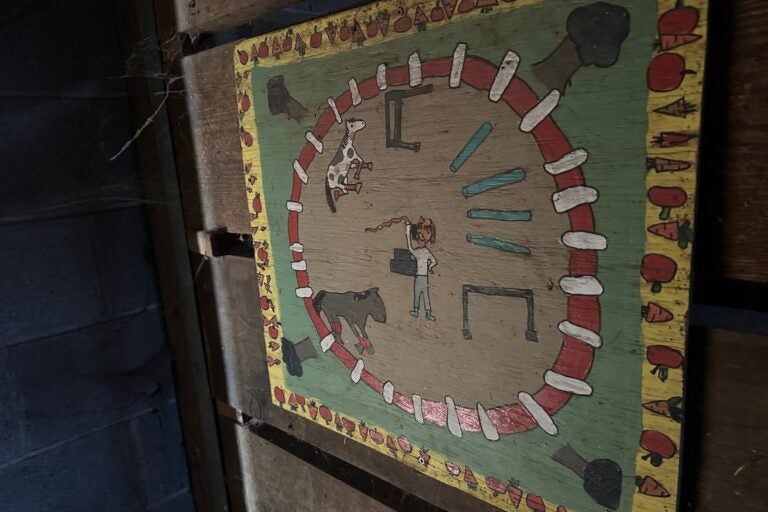

For the past 30 years, Hiner has been leasing the former Philadelphia Police Department horse mounted police barn known as McCarthy Stables, built in the 1970s from the city’s parks and recreation department for a nominal fee.

“Part of the lease agreement was that she would be in charge of all capital improvements, and when you’re running a small nonprofit barely getting by each year, the last thing you’re thinking about is redoing a roof or fixing a window when you’ve got kids and horses to feed,” chimed Kareem Rosser, executive vice president at Work to Ride and an alum of the program himself.

Rosser said that state grants, city support and dozens of private donations mean the organization can finally rehab the complex. So far, the organization has raised nearly $12.5 million out of its total $15 million goal.

But it took nearly a decade of planning and hard work to make such a vision get close enough to happen.

“We’re just a couple million dollars short from the overall goal and fully funding the project,” Rosser said. “But we are just happy where we are in the process. We’ve made incredible progress. It’s been a lot of long hours, a lot of sweat and tears.”

The earliest the new indoor arena as phase one of the project could open would be in April 2025. The barn renovation and the rest of the facilities would be in phase two to wrap up next year.

The project is a major accomplishment for alums like Rosser, who is now in his 30s and leveraged his horse polo playing skills into scholarships to a private high school and college.

The first time he visited the barn, he was 8 years old and tagging along his older brothers. That’s when he would sometimes hide in the hay loft above the horse stalls to avoid farm chores in cold weather, he said as he walked through the old barn.

“There are a lot of us who started very young and you can see the impact the organization had on a lot of us,” he said. “Many of us now have children [of our own] who are starting to ride. We’re building a legacy.”

It was serendipitous that Rosser himself even moved back to Philadelphia. He went to Colorado State University for college, but came back home in 2016 to work in finance.

He wasn’t expecting to come home, but he said he wanted to be closer to his friends and family.

The Rosser siblings were regulars at the Fairmount Park barn over the years — a big family with six children who shared a rowhouse with their mother in a West Philadelphia neighborhood known as The Bottom, near the Philadelphia Zoo.

Rosser dedicated his first book, a memoir of his journey to a national polo championship, to his loved ones, who were abruptly slain in Philadelphia.

His older brother David, who was once a regular at Work to Ride and would have been in his 30s too, was killed in a shooting in March 2020. His murder remains unsolved. His best friend, Mecca Harris, also a talented young woman and Work to Ride polo player, was murdered when she was 14 years old.

“I didn’t want to just be this poster child of the organization but really come back and serve,” Rosser said. “It was also always really important to come back and be an example for the children as a mentor. Polo is a contact sport, it’s second to NASCAR when you think about danger.”

His favorite part?

When the kids accomplish their goals and beam with pride they might not have in many other areas of their lives.

“I think that a lot of the kids show up with a lot of trauma and fear, but it’s great to see the confidence that the kids build over time and the trust between the horses and the kids themselves,” he said.

Rosser is now working for the nonprofit after a role as a board member, to institutionalize its processes and set up a financial structure that can make capital projects, such as the indoor arena and barn renovation, a reality. The project was also awarded $200,000 from the Pennsylvania Redevelopment Assistance Capital Program in November, in addition to the local share of gaming revenue.

And there are many more alums who are thriving in the world, like Richard Prather, who was visiting from Houston to see the sports arena’s progress. Now in his 40s, Prather started at the horse stables when he was 14 years old.

“I’m extremely proud of Kareem, there were many attempts over the years to get the arena going and a lot of roadblocks,” Prather said. “When Kareem first came around to the barn, he was this little kid just running around. You would never dream that this is where we would be today. I am really proud of him for making this vision come true.”

Working toward a legacy

Horseback riding lessons for the public is one way the organization raises money for its operations.

“This time of year we aren’t even having lessons [at the Fairmount Park stable],” Rosser said. “Having this facility, not only does it allow us to operate year-round and be able to keep the lights on, but it’s also going to give the kids a safe and comfortable place to ride. The arena itself won’t be heated but it’ll be a lot warmer than if we didn’t have this space.”

Plus there will be special flooring, known as footing, that’s softer for horse hooves and riders’ comfort.

And it will allow for horseback riding on rainy days too when it would otherwise be too muddy for the horses during the spring and summer months.

“We’ve never been able to practice [polo] year-round to be able to compete at a high level. We found ways to win but typically we were practicing and playing a game at the same time,” he said.

So this winter, most of the barn inhabitants are two dozen barn cats, dubbed the stable construction site managers.

“When the barn is at full capacity there’s kids, horses, goats, chickens,” he said. “We probably have about 30 barn cats.”

For 18-year-old student athlete Marc-Anthony Harley, he was tapped to train some retired racehorses for polo games in partnership with another student who worked with the horse on show jumping.

Harley traveled to Kentucky for a competition in October, where his team won a blue ribbon. He says he can’t wait to move back into the refreshed barn.

Because for him, riding horses is one way to help him deal with hard days in life.

“It just makes me feel better. I get off [the horse] and I’ll feel like, refreshed. I won’t have this, like, pent-up anger, this energy that I like, need to release,” he said. “Yeah, it’s almost like therapy.”

He was brimming with pride recounting his experiences and goals for the future. He has been in the program for the past 10 years.

“It ain’t easy, I can tell you that,” Harley said about riding horses in polo games. “It’s very physically taxing. You use your lower body to hold on to the saddle and stay on because it’s almost like a motorcycle.”

When he goes to college, he plans to become a zoologist.

“I want to study animals, evolution, where they came from, their behavior, how they survive in their natural habitat,” he said.

Dreaming of a future

And for student athlete McLaughlin, he plays other sports, but riding horses is a different feeling.

“Coming here to the barn, it’s like another home for me,” he said. “I’ve learned responsibility, time management as well in and out of school. It’s about being responsible for yourself and the horses, so you have to learn to accommodate their needs as well as yours and be safe.”

None of the youth in the program can continue riding horses if their grades are not in order, and there’s a partnership with tutors to help make sure that happens.

Some of those lessons include something well-known in the agricultural world, such as the difference between hay and straw, despite living in a major city where concrete is more common than grass.

“The greener stuff at the front, that’s hay. He pushes it around because they all do that. The yellow stuff at the back, that’s straw, the stuff [horses] pee and poop on,” McLaughlin said, pointing into a horse’s stall.

He said he wants to go to college to pursue his dream of a career that combines fashion and dermatology.

Horse polo is a contact sport, just like ice hockey, so whether during a game or rides, falling off the ponies is common.

“You’re going faster speeds than you would regularly on ice, but it’s like hockey because you’re passing the ball back and forth from teammates running around on horses,” he said.

And when he’s ever been scared on the back of a horse?

“I just go with the flow,” he said.

Subscribe to PlanPhilly

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.