Exploring paradox of Jefferson as freedom fighter, slave owner at Constitution Center

The legacy of slavery at Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello estate in Virginia is the focus of an exhibition now on view at the National Constitution Center in Philadelphia.

“Slavery at Jefferson’s Monticello” presents a paradox: how could a man who publicly decried the institution of slavery as a “deplorable entanglement” himself own as many as 175 slaves at any given time?

It’s not an easy question to answer. It took a collaboration of the National Museum of African-American History and Culture and the Thomas Jefferson Foundation at Monticello.

“His views were not what we consider modern views,” said Susan Stein, senior curator at Monticello. “He thought that slavery was so horrible that it changed people forever, and that no master and no slave could forget slavery — would carry with them that pain and that experience. He never envisioned the society we know now.”

Jefferson supported several plans that would gradually emancipate African-Americans, including repatriation to Africa and sending them into the western territories of the U.S.

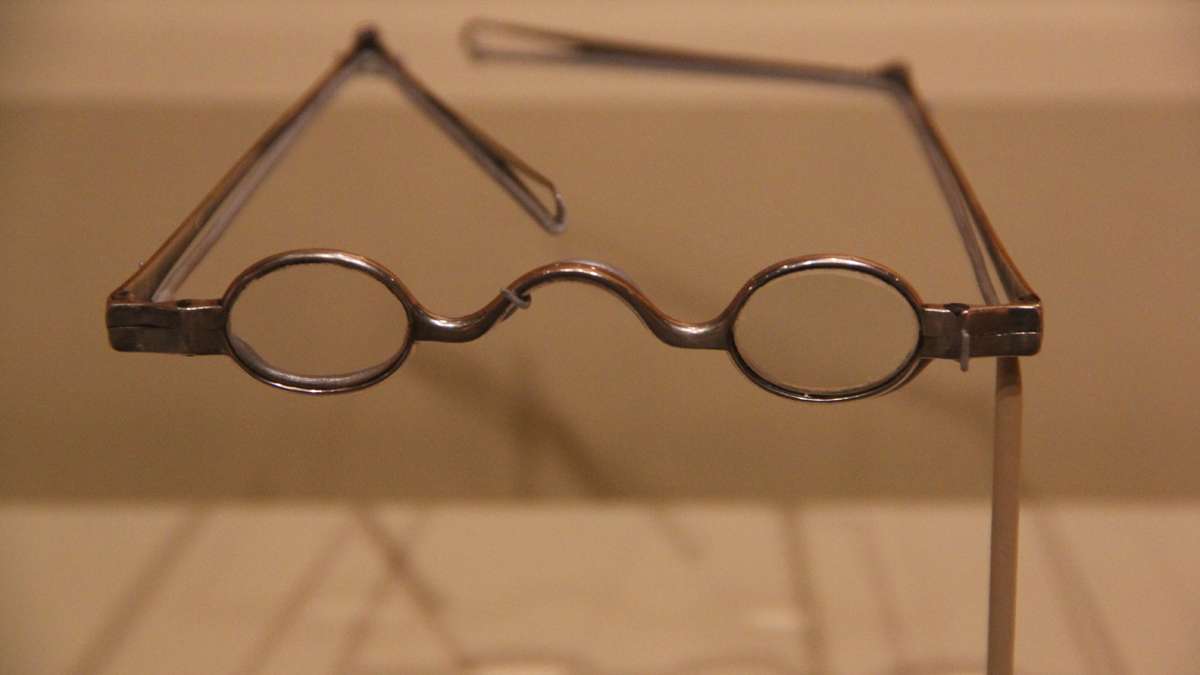

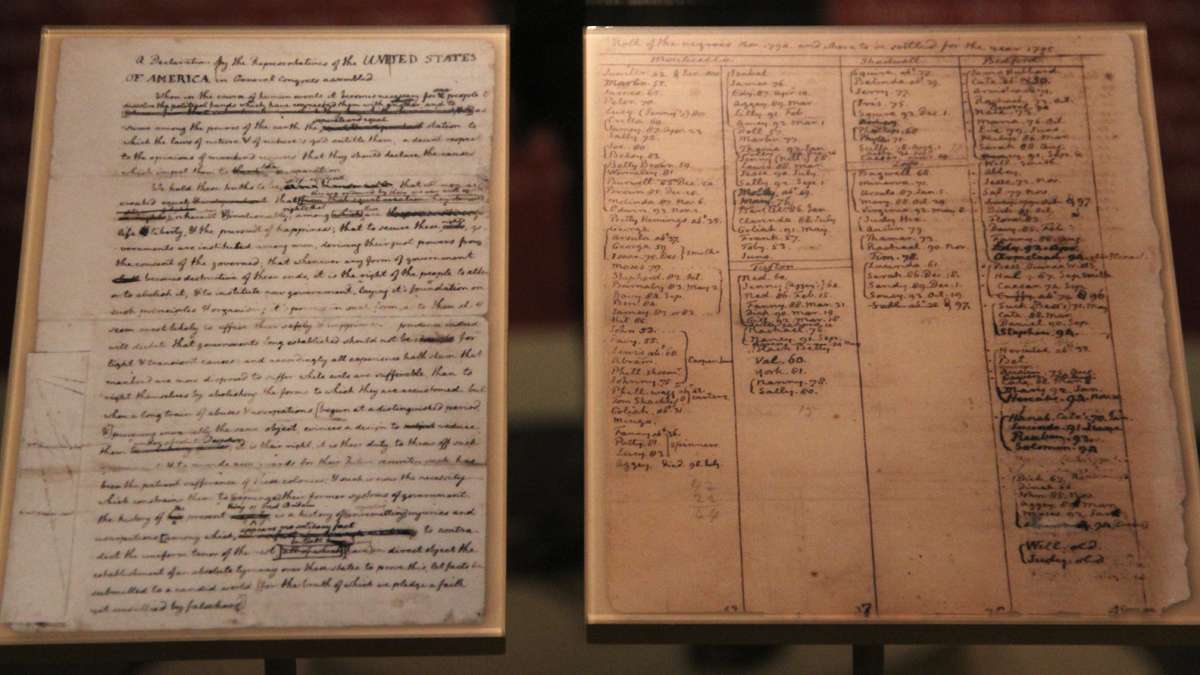

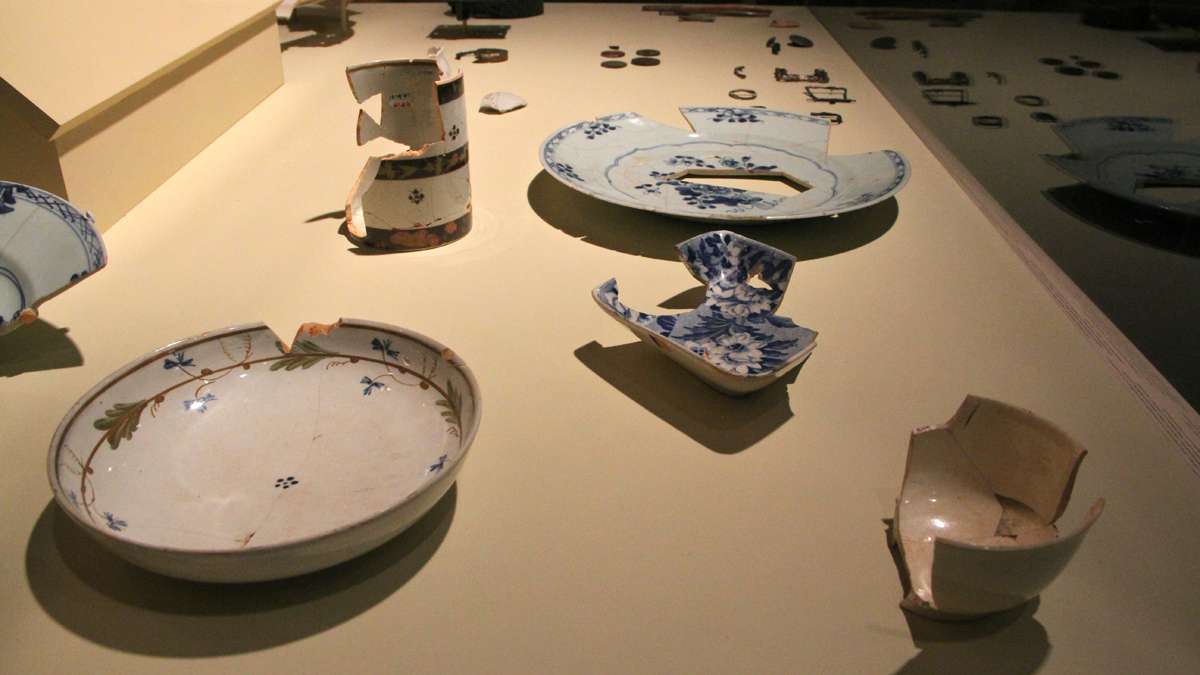

The exhibition puts the lifestyle of master and slave in stark contrast. On one wall is a video projection of the Declaration of Independence, which Jefferson drafted. On the opposite wall is a projection of a ledger in Jefferson’s hand listing the names of his slaves and the years they were born. Further on are glass cases with silver serving sets and items used by the Jefferson household, contrasting with the rough crockery and hand tools used by his slaves.

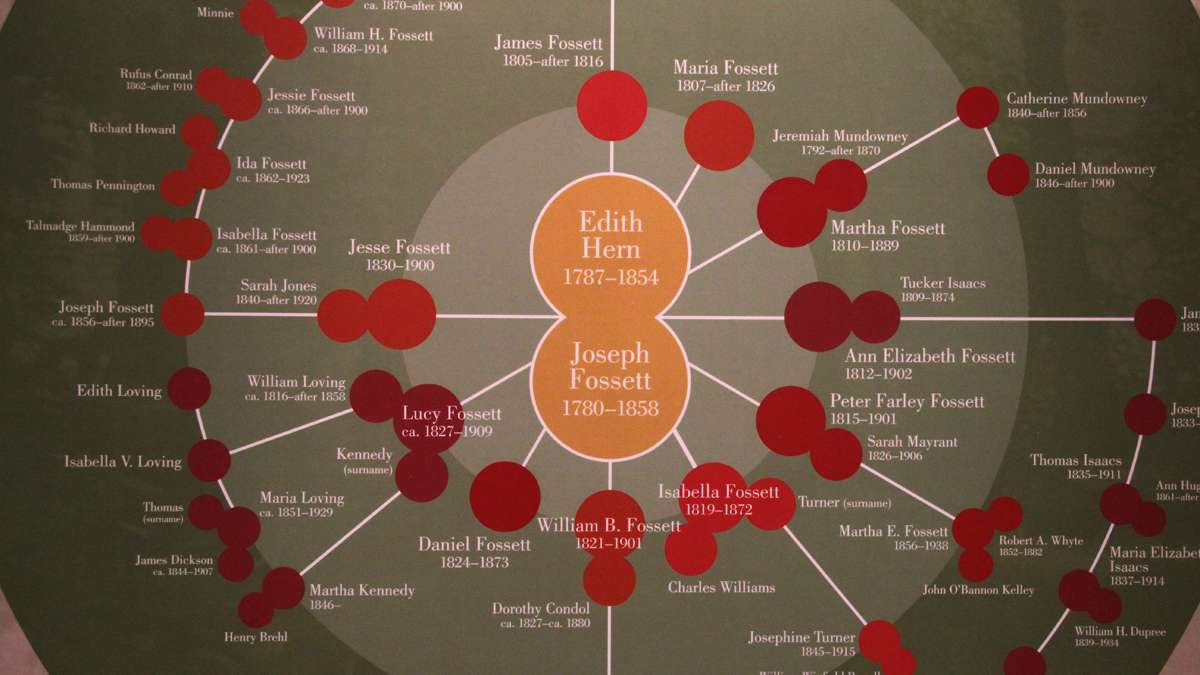

The exhibition tracks the histories of six families owned by Jefferson – the Hemings (by far the largest family), the Grangers, the Fossetts, the Gillettes, the Herns, and the Hubbards. The fact that we know their names is a testament to the promise of American idealism, said co-curator Rex Ellis of the National Museum of African-American History and Culture.

“These families remained intact. They remained intact with male and female heads of households — unheard in Colonial America,” said Ellis. “It happened in Monticello. That’s the uniqueness of the environment Jefferson created. They were large families that were allowed to keep their families intact.”

Those families live on to this day. The exhibition features video testimony from current descendants of Jefferson’s slave families.

On of them is Bill Webb, whose great-great-great grandfather Brown Colbert was a blacksmith owned by Thomas Jefferson and a grandson of the Hemings family matriarch, Elizabeth.

Brown Colbert made a request of his owner one day, said Webb.

“He asked to be sold in 1806 because the woman he was in love with was owned by somebody else,” said Webb, 72. “Jefferson finally sold him for $500 and my ancestor was taken to Lexington, Virginia.”

Webb said his ancestor later went to Africa to join a former slave colony in Liberia, where he almost immediately died of malaria.

The traveling exhibition will be at the National Constitution Center until Oct. 19.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.