Panic is the biggest enemy for those caught in a rip current

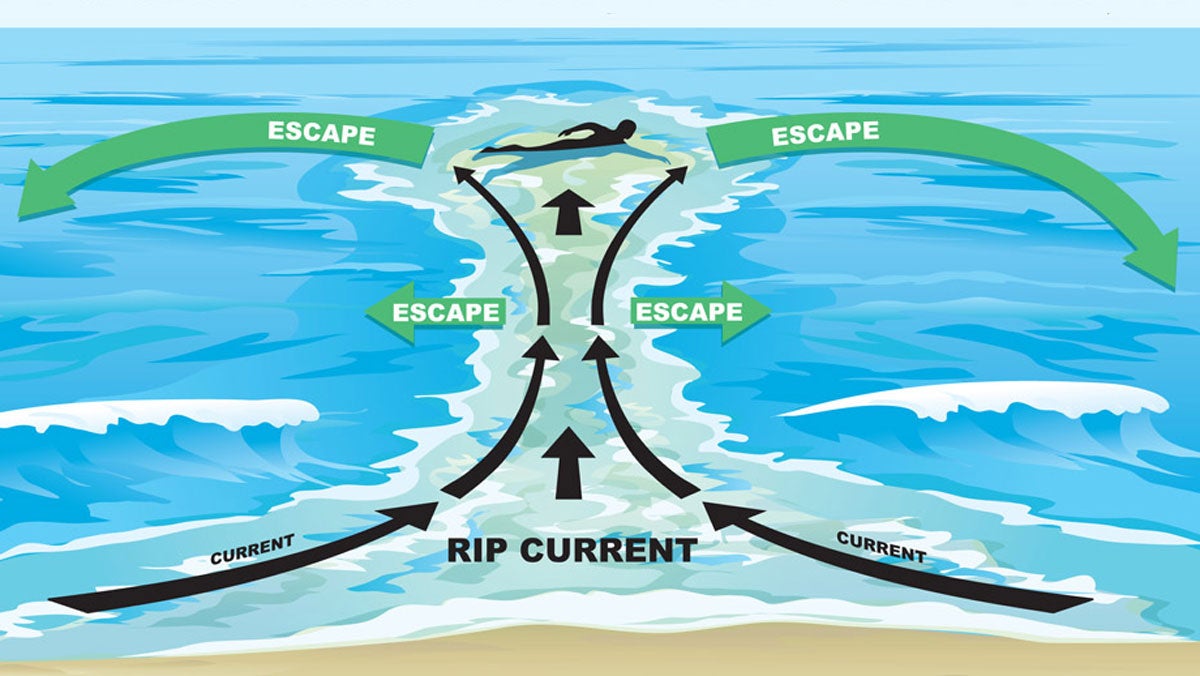

(Graphic courtesy of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration)

“Don’t Panic.”

In Douglas Adam’s brilliant sci-fi comedy “The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy,” that phrase is written on the cover of the titular, fictional guide in what the author describes as large, friendly letters. It’s good advice in many circumstances.

In the ocean, especially for those caught in a rip current, it could save your life.”Once the panic sets in, everything changes,” said Lt. Ronald Kirk of the Ocean City Beach Patrol. Your heartrate spikes, your breathing becomes fast and shallow, and worst of all, you start making bad decisions. “If you panic, it could be doomsday. You don’t think straight anymore. That’s why we’re here.”

If a lifeguard sees someone being pulled out by a rip current, he will head out with a red plastic floatation device known as a torpedo, and either pull the swimmer in or wait for help from another guard, usually responding with a jet ski.

Kirk, who’s been on the beach patrol for 46 summers, says the first thing the guard tries to do is calm the person down. A swimmer terrified of drowning is hard to manage, sometimes striking out at potential rescuers.

People are buoyant. If the swimmer could calm down and float, rather than struggle against a strong current, there would usually be plenty of time for rescuers to arrive.”Your whole psyche starts to change once you begin to panic,” said Joe Miketta, a meteorologist with the National Weather Service in Mount Holly, where the team tracks the potential for rip currents along with other data on weather, wind and water.

The Mount Holly office presents regular rip current forecasts through the summer, delineating low, medium and high risk. The forecast will continue until Sept. 30.According to Miketta, 2017 has been a bad year for rip currents, with at least five drownings attributed to the currents in New Jersey this summer, and a sixth possibly connected to the phenomenon. More than 100 drownings a year are attributed to rip currents, according to data from the United States Lifesaving Association, and about 80 percent of rescues.

Kirk said most Ocean City rescues involved helping someone in from a rip current. Depending on the waves, he said, guards could have a day without a rescue, but on heavy days they could see 50 in Ocean City, just one island along the long New Jersey coast.

Tides, waves and gravity

Rip currents come down to physics. Kirk uses Newton’s third law to explain them: for every action there is an opposite reaction. Out at sea, winds put energy into the water, energy that is expressed as waves. Those waves roll in to shore. When they hit the beach and bounce back, that energy heads back out to sea.

“It’s basically a gravity current,” says Stewart Farrell, the founder and director of the Coastal Research Center at Stockton University in Pomona, N.J. As a wave moves through the ocean, he explained, the water carries the wave’s energy, but that energy barely moves the water, at least until the wave begins to break. That’s why no matter how big the waves get, surfers can sit outside where the waves are breaking without moving. In deep water, the wave moves through the ocean. When there is not enough room between the surface and the bottom, the wave breaks, tumbling over itself.

That breaking wave now moves water, which rushes in toward the beach, sometimes taking boogie boarders, kayaks, surfers and others for a ride along the way.

“If the waves are of a substantial size, that raises the level of the water at the shoreline,” Farrell said. “Then gravity comes into play, and the water has to go back out.”

Physics won’t allow the water at the beach to be a couple of inches higher than the nearby ocean, so that water flows back out. On a perfectly flat beach on a perfectly still afternoon, Farrell said, that water would flow out evenly across the length of the beach. But in the real world, nothing is that flat or still. The shape of the shoreline, the depth of the water, the absence or presence of sandbars or jetties, the force of the next set of waves coming in all influence the flow of that water, which can form in to a defined stream known as a rip current.

“Rip currents have had a lot of funky names. They used to call them the undertow,” Farrell said.

According to Kirk, those currents don’t always match the diagrams put out by public safety organizations. They don’t necessarily run straight out into the open water. They may run parallel to the beach for a time, turn at a 45-degree angle, or even zig-zag as the water makes its way back from the beach.

While there are some spots where they tend to form, especially where previous currents have dug out a channel deeper than the surrounding sea bottom, they can also form quickly anywhere along the beach.

“They’re often in the same location, but you can’t depend on that to be the case,” said Kirk. At times, guards have moved swimmers away from a spot where a rip current has formed repeatedly through the summer, only to bring them in to a spot where a new rip current formed.

Like a ski lift for surfers

When the waves are at their strongest, so are the rip currents. On the heaviest days, it can be tough for surfers to fight their way through those big waves, so most surfers look for a rip current to carry them out through the break.

In many places along the Jersey shore, wooden or stone jetties have been put in place in an effort to slow beach erosion. While in other places the rip current can move around, those act as a guide for the water, meaning there is often a rip current right along the obstacle. That’s why many surfers paddle out close to the rocks.

“It looks a little crazy, but it really works,” said Kirk.

Sandbars can have a strong effect on rip currents. Sandbars form as the sand churned up by the waves settles to the bottom, Farrell explained. But everything in the surf zone, including the sandbars, is always in flux and can change rapidly.

Water pushed in by the waves and trapped in the area between the sandbar and the beach, known as the gully, often travels along the beach in a strong current leading to a channel between the sandbars. That can mean a strong current pulling toward the open water.

Like every lifeguard, Kirk says swimmers should swim when guards are on duty, and trained and equipped men and women are ready to help if you get in trouble. But he recognizes that sometimes, people swim without the guards. He said a strong swimmer might be able to swim against a rip current, but it’s not a good idea – it’s more likely to lead to exhaustion, especially when added to the panic mentioned above. Instead, try to swim out from the current, or else just allow it to carry you out. It may take you up to 75 yards from shore, but as he said, you can float and take your time.

“Just try to stay as calm as possible, and when you feel the rip current has stopped pulling you out, try to get your head far enough above water to see where the rip current isn’t,” Kirk said. “Choose a path and then swim straight in or ride a wave in.”

Water rescue experts warn that every year, people drown while trying to rescue others from a rip current. They suggest those who see a swimmer in distress call 911, and try to throw out a floatation device.

It’s not a swimming pool

The National Weather Service crew has gathered data on rip currents since 1998, Miketta said.

“We’re still trying to fine tune the parameters. Every year we learn a little bit more,” he said. “The problem is, we’re wondering what else we need to do so that people understand the dangers.”

They’ve found some patterns. For instance, the most likely time for a fatality in the ocean is early Sunday evenings. Miketta said they have theories as to why, but nothing certain. “All we know is how the numbers turn out.” They also look at other causes of ocean drownings, including surf break injuries. Sometimes, it comes down to carelessness, such as swimming after midnight or while intoxicated.

Many shore visitors are used to swimming in pools or lakes, he said, and may not be prepared for the complex world of waves, tides, currents and rip currents that come with swimming in the ocean. He said some who get caught in a rip may not realize that they would do better to swim out of it to the side rather than try to fight their way in.

“It’s just a narrow channel of water that moves out from the shore back toward the ocean,” he said. If you happen to be in that little current of water, it carries you with it. You might panic, but if you just remain calm and swim parallel to the shore, you can get clear.”Beach patrols, the New Jersey Office of Emergency Management, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, or NOAA, under which falls the National Weather Service and many other organizations are working to educate beachgoers about rip currents. Miketta said they don’t want to keep people form enjoying the water, but instead to help people understand a little of the immense world they enter when they dive into the Atlantic.”The ocean is great as long as you respect it and understand what it can do,” Miketta said.

How to identify a rip current:

- A channel of churning, choppy water.

- An area having a notable difference in water color.

- A line of foam, seaweed, or debris moving steadily seaward.

- A break in the incoming wave pattern.

If caught in a rip current, NOAA advises:

- Stay calm.

- Don’t fight the current.

- Escape the current by swimming in a direction following the shoreline. When free of the current, swim at an angle—away from the current—toward shore.

- If you are unable to escape by swimming, float or tread water. When the current weakens, swim at an angle away from the current toward shore.

- If at any time you feel you will be unable to reach shore, draw attention to yourself: face the shore, call or wave for help.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.