Everything is ‘specifically’ illuminated: neuroscientist-turned-artist uses photolithography to light up the brain

Listen

Greg Dunn is a neuroscientist and artist who depicts neurons in mediums such as microetchings and ink. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

A neuroscientist-turned-artist is using physics to capture one of the most complex entities out there: the human brain. But can he do it?

Greg Dunn‘s fourth floor space, just north of Center City, has all the signs of a typical artist setup: work tables, paints and photo chemicals scattered between finished and unfinished works. But this neuroscientist-turned-artist has also brought in some high-tech experimentation to take on a rather ambitious goal: creating the largest artistic rendering of the human brain.

Dunn’s approach is the culmination of decades of exploration into the intersection of neuroscience, art and the surrounding world, and the results are shimmering, reverent “micro-etchings,” portraying the complex inner workings of the brain.

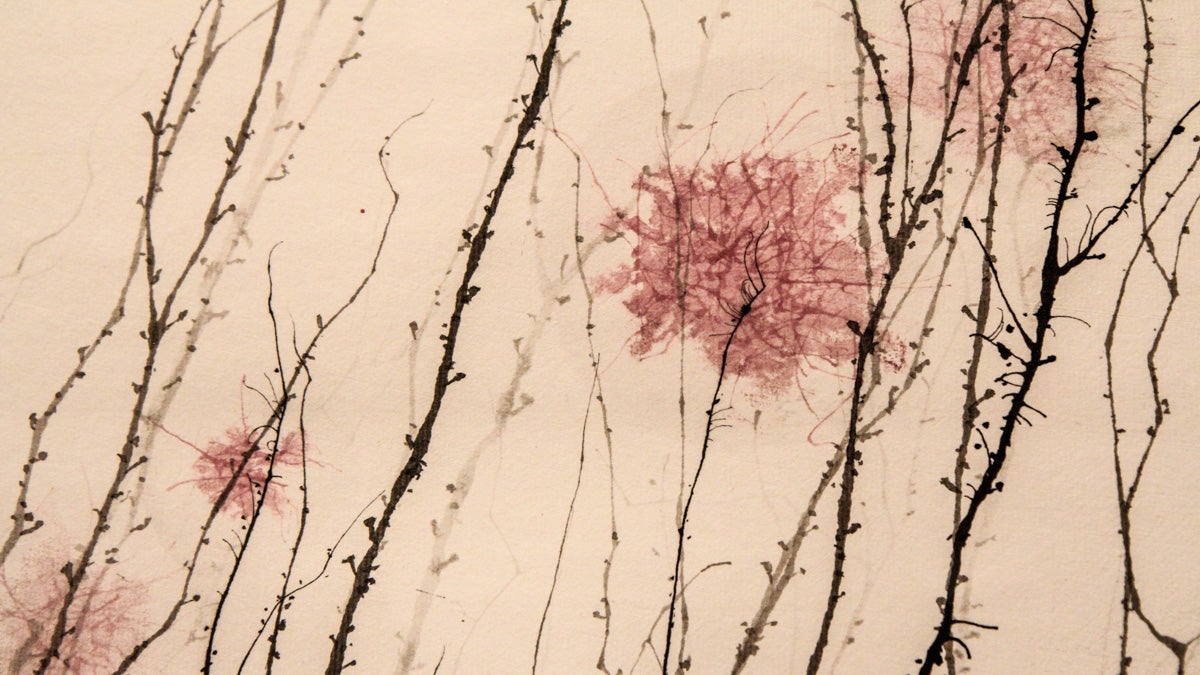

Pranayama by artist and neuroscientist Greg Dunn. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

The microscope as inspiration

Ever since he was a kid, Dunn has thought a lot about how he thinks, and more specifically, how his mind perceives the world.

“I would stare at the intersection of grout on tiles on the floor, and just fixate on that one point for as long as I possibly could, until my visual field would disappear,” he recalls.

Fast forward a few decades, a much taller, glasses-wearing Dunn has continued that exploration through meditating (yes, he even has his own sensory deprivation tank) and pursuing a PhD in neuroscience.

To him, studying the brain is kind of a no brainer: it’s the core of all perception. And yet, the billions of neurons that comprise it and chaotically mix to create consciousness, thoughts and emotions continue to baffle scientists.

“What an insane concept it is that you start with these cells which are just splaying themselves out randomly into the space around them, and then just through the collective behavior of all of them, organizes themselves into these incredibly elaborate circuits,” he says.

Dunn spent years examining these basic building blocks under the microscope. But it wasn’t just the science that struck him. Like an astronomer looking out into space, Dunn found a deep beauty in the brain. The random patterns of neuron branches, or dendrites, drew him in. He’d make connections outside the lab.

“You see it in cracks in the pavement or ice, you see it in lightening bolts, you see it in the orientations of galactic superclusters,” he says. “It’s shape is independent of size and scale.”

The way that researchers stain neurons – turning them black on a gold surface – also reminded him of traditional asian art styles.

On the side, he started to paint.

A meditation on the neuron

Dunn practiced a zen painting technique, involving simple ink strokes, as an attempt to express the neuron’s essence. He says thanks to a little help from nature, he hit a breakthrough one evening.

“I think a fly landed on the page and I tried to blow it off, and my breath blew the ink and splattered it around on the page,” he recalls. “And that to me was the eureka moment. Because the ink wanted to form those patterns. Nature wanted to organize itself into these fractal linear lines which take these random twists and turns to their destinations.”

An excerpt of Greg Dunn’s piece ‘Alzheimer’s Tangles’. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

An excerpt of Greg Dunn’s piece ‘Alzheimer’s Tangles’. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

The resulting works appear reminiscent of minimalist landscape paintings: what seem like delicate trees with pink floral clusters on a rice paper scroll at a closer look, are actually neurons mixed with alzheimer’s tangles.

After finishing his PhD in 2011, Dunn moved into the art studio full time. He felt constrained by the narrowness of his research.

He started using metals to depict phenomenons like neuron clusters processing information.

He then turned to a colleague, Brian Edwards, an applied physicist from Penn to add more dimensions and nuances to the work.

“I’m interested in solving problems, and Greg’s art presents a lot of unique problems,” says Edwards. “He and I had a lot of fun trying to create a physical manifestation for what his vision is.”

Over the span of a year and a half, the two developed their micro-etching technique. It involves optical engineering, and more specifically, micro-lithography, a technology used to make microchips.

The etchings, often a combination of stainless steel, aluminum and gold sheets, don’t have color, but they’re reflective. The basis are Dunn’s carefully sketched neurons, but through a series of transformations, the two apply reflective technology similar to what’s used in microchips.

“It’s mesmerizing,” says Evi Numen, exhibits manager at the Mutter Museum of The College of Physicians of Philadelphia who has organized a showcase of Dunn’s work. “They’re unique in being able to convey the complexity of the neural circuits.”

The effect may be hard to see directly, but the pieces take on the added dimension as a person moves around it.

“Every piece we do is very specifically illuminated. It’s not enough to just say ‘I want the light going in this direction,'” says Edwards.

As a person moves around a piece, the reflection of light creates the appearance of neurons in action. Pulling this off has involved a lot of programming on Edward’s part, plus teeny tiny patterns imprinted on metals and plastics.

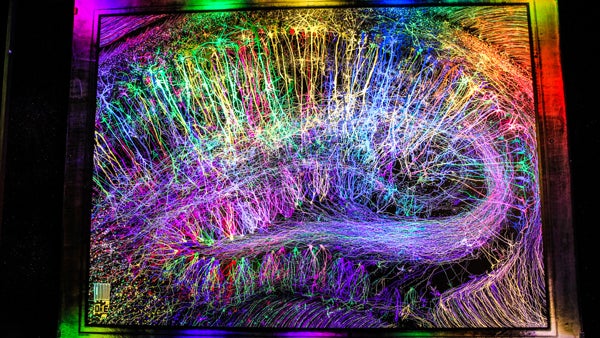

‘Brainbow Hippocampus’ mimics a recently developed genetic technique called brainbow, which adds distinct colors to different neurons in the brain so researchers can easily track them. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

‘Brainbow Hippocampus’ mimics a recently developed genetic technique called brainbow, which adds distinct colors to different neurons in the brain so researchers can easily track them. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

“This is basically me painting a forest,” says Dunn, referring to his depiction of the hippocampus of a mouse. “The only difference between this and painting a landscape is that I use a microscope to get my inspiration.

Science groups and journals have commissioned Dunn’s work. He’s now working on a giant, 8 by 12 foot cross-section of the brain for the Franklin Institute, thanks to a National Science Foundation grant.

But as accurate as a lot of these pieces are, Dunn wants to redefine the whole idea of science art. It’s not just a reflection of the science. He wants viewers to experience a deeper appreciation of the brain, its vastness, complexity and beauty through merging that with artistic renderings.

The process, he says, has been gratifying and humbling.

“When you actually make something, you have a greater understanding of what you’re dealing with,” says Dunn. “And as complex as these images are, they are millions of times less complex than brain actually is.”

A showcase of Dunn’s work, Mind Illuminated, is now on display at The Mutter Museum.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.