Under the bridge, a world of pain not so far from any of us

A view of the 'Badlands' of Kensington, Philadelphia. (Courtenay harris Bond)

The suffering I witnessed in the course of some recent reporting I did on the opioid epidemic weighed more heavily on me than any previous work ever had.

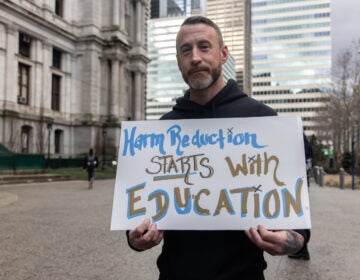

I was working on a radio story about safe injection facilities, as well as a more comprehensive story for Drexel University’s Dornsife School of Public Health magazine about how the epidemic is affecting Pennsylvania.

One afternoon, for instance, a pair of harm-reduction advocates from the Philadelphia Overdose Prevention Initiative took me under a bridge by the Conrail tracks in the “Badlands” of Kensington. This is an area of Philadelphia that a U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration agent had told me was the largest open-air drug market along the East Coast. Notebook out, recorder and mic still in my backpack, I was trying to engage people I had just seen shooting up.

One man was scampering around with a bare foot, seemingly oblivious to the carpet of used syringes on the ground. Another guy was in the heroin grunts, screeching and groaning, coming in and out of coherence, and bleeding from the back of his neck. When he could talk, he told me that his name was Anthony and that he came here every day from South Philly to buy and use heroin but otherwise held down a job in a warehouse. He said he was a veteran. He was standing in front of what looked like someone’s home, a rocking chair and a bed carefully made and tucked underneath the bridge, somewhat protected from the elements.

Another man, who would only give me his nickname, “Junior,” told me he had been doing speedballs — heroin mixed with cocaine — for years. Now 42, Junior said he was fed up with himself and this life and really wanted to take care of his wife and young child. He told me he was from Puerto Rico, that he worked as a contractor. Motioning to his heart, he said he does drugs to deal with his “hurt feelings.” He was neatly dressed in a clean, black parka, sunglasses perched across the top of his baseball cap. He spoke quietly. Talking to him, I felt a tug of hope that he would find a better life.

Another guy I met there had teardrop tattoos under his eye, which supposedly meant he’d killed someone. I saw him finish injecting a young woman in the neck and then use his belt as a tourniquet to find a vein in his own arm. He refused to tell me his name but said he was in his 30s and that he became addicted to opioids after someone shot him 14 years ago.

He said he was a musician and a writer and that he would let me take his picture if I promised to share it widely on social media. I refused to bargain. He ended up posing for some photos anyway, checking the results on my camera phone until he was satisfied. Then I watched as he and his girlfriend climbed the garbage-strewn bank up out from under the bridge, wondering where they were going, where life would lead them next.

That night, I had tormented dreams about the pain I had witnessed in those men. I woke the next day tired and troubled. I decided that the least I could do was give them the number for the National Drug and Alcohol Treatment Hotline. I knew that many people had probably already tried to help the people I’d met under the bridge, but I felt that I had to take some kind of action, even if it was small. I could no longer just ask questions and listen.

So I left a couple of voice mails, one with a 63-year-old heroin user named Mike, who had said that he wanted to get help, and another with Anthony, who had given me his number so we could talk when he was feeling better. In my messages, I repeated the hotline number: 1-800-662-HELP.

Junior actually answered his phone and spoke to me again for a while in his soft voice. He said he was dedicated to getting off drugs but that he hadn’t been able to in previous treatments. He said he wanted to call me later in the week to let me know what happened, but I never heard back from him. In following up about a photo I took of him, his family told me that Junior is now in jail.

I didn’t have a number for the man with the teardrop tattoos, but I did have his email address. I wrote to him, thanking him for our conversation the previous day, and I shared the hotline number in case he didn’t already have it.

Immediately in my inbox popped his three-letter response: “WTH?”

I felt a flush of panic. Had I just infuriated a guy who had supposedly killed someone and who had the name of a famous Russian assault rifle as part of his email address — albeit misspelled? I felt stupid and ashamed. Who did I think I was? Mother Teresa?

When I called a friend for consolation, she told me that I wasn’t even on this guy’s radar and that he wasn’t going to waste the gas money to try to come get me — that is, if he even had a car. I hoped she was right.

Since then, I have continued to worry, not so much about my safety but about the well-being of those I met in the Badlands. Reporting on the opioid crisis has changed the way I view people who have substance use disorders: I no longer see them as “addicts” but rather as individuals whose problems have led them down one path, while mine have taken me down another. Ultimately, this work has shown me how easily any of us could find ourselves fumbling close to the edge and possibly even tumbling out of control.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.