The changing nature of paper reflects the changing way we communicate

If music has charms to calm the savage breast, can art soothe the distraught body politic?

“Paperscapes” at the Philadelphia Art Alliance seems an appropriate place to find out. After all, paper is the substance that launched the nation: Recall that, referring in 1776 to the Declaration of Independence, Pennsylvania’s John Dickinson observed that America was setting sail in “a skiff made of paper.” True, Dickinson didn’t endorse the enterprise, but it all worked out.

At least, so far.

In “Paperscapes,” a quartet of artists explores the changing nature of paper. Though paper is no longer the sole, or even primary, medium of mass communication, are there still messages best rendered in it, if not on it? The answers exhibited here are imaginative and reflective of the current state of public discourse.

Alternative books

Susan White’s “Encircle” (2017) embraces a spacious, chandeliered ballroom at PAA, a center for contemporary craft and design housed in the elegant Wetherill Mansion just off Rittenhouse Square. The artist repurposes books, deconstructing them to create something new. For “Encircle,” she tore pages into strips of varying width and spooled them into hundreds of little boulders, with which she built a turreted castle on the wall. On close inspection, the “stones” reveal random words, old text now all but obscured.

Susan White’s “Encircle” (2017)

Susan White’s “Encircle” (2017)

So transformed, would those books feel overjoyed to be freed from dusty shelves? Or dismayed at becoming mere objects? And what are we to make of it? Is this deconstruction the ultimate fate of all words on paper? Of the written word itself? Does the format affect the knowledge it contains?

While ethereal, White’s piece is a tangible reminder of what is happening to old media, and more immediately, of attempts to undercut traditional information sources.

Neither here nor there

Sun Young Kang’s installations dwell in uncertainty. “In Between Presence and Absence” (2009) fills the floor of a small, dark room with the ghosts of bottles, bowls, cups, and jars, sculpted from handmade paper. The scene resembles Pompeii, after the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius covered everything in volcanic ash. Kang’s sculptures, now hollow, suggest what they once held. It’s a work of dualities: dark and light, empty and full, here and gone. Viewers experience yet another vexing contradiction: They can look into, but not enter, the installation space.

Sun Young Kang’s “In Between Presence and Absence” (2009)

Sun Young Kang’s “In Between Presence and Absence” (2009)

Conversely, Kang’s “In Between” (2014) draws us in, a floating cloud of paper tubes suspended knee-high, over motion-sensitive lights. Circling the work causes the cloud to be illuminated in sections — light shines up from the floor, through the tubes, and onto the ceiling to create a sky of luminous spheres. Circle faster, and the whole cloud comes alive; stand still, and lights flicker out, like distant lightning in a summer sky. The uncertainty infusing Kang’s work allows the mind to escape, to rest.

I, me, mine

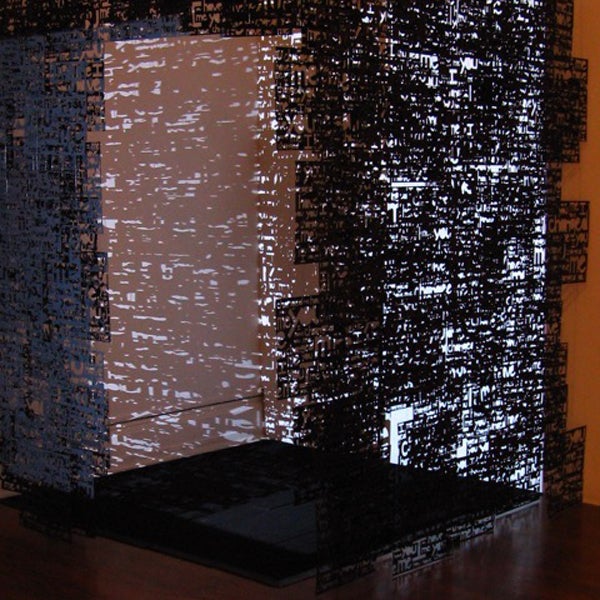

Not so Dawn Kramlich’s “Solipsist’s Cell” (2013). It is pointedly prescient, a jail-like enclosure built from squares of black matboard into which the artist has laser-cut the words “I,” “me,” “changed,” “have,” and “you.” Outside the cell, a projector shines through its walls, washing the interior in disjointed word-shadows from which you can’t help but make sentences:

“I have changed.”

“I have changed you.”

“You have changed me.”

“You have changed.”

Dawn Kramlich’s “Solipsist’s Cell” (2013)

Dawn Kramlich’s “Solipsist’s Cell” (2013)

The variations keep rotating, fittingly for the solipsist, who believes in self as the only reality. In “Solipsist’s Cell” and “Mind’s Forge” (2013), in which words pool on the floor like an oil spill, Kramlich portends a world in which language withdraws into ever-tighter knots until we no longer speak to one another, but only to ourselves in an endless, reinforcing loop.

Beautiful destruction

Intellectually, Elizabeth Mackie’s “Ortler Kettles” (2015) is best appreciated if you know that kettles are voids formed by retreating glaciers. But her rendering is so beautiful that it’s bliss to remain ignorant of that intention. Large sheets of handmade paper pierced with leaf-like shapes hang in arctic blues, tropical greens, and a rainbow of whites, giving the appearance of a roomful of Battenburg lace curtains — if not for Kaitlin Paston’s accompanying soundscape, an insistent trickling that brings to mind, well, you know.

Elizabeth Mackie’s “Ortler Kettles” (2015)

Elizabeth Mackie’s “Ortler Kettles” (2015)

Of course, those who believe global warming estimates to be overblown may interpret the sound to be a nearby brook, and will enjoy the curtains unfettered.

Are we being soothed?

So returning to the original question, whether art soothes the body politic, the unsatisfying answer is that it depends on who’s creating and who’s looking. “Paperscapes,” maybe ironically, maybe appropriately, really is like a book: Skimmed like light fiction, it’s visually intriguing and enjoyable. Read like a Russian novel, with allegory and subplots about deconstructed books, word-prisons, the world melting away, and the joy of uncertainty, it is beguiling and unsettling.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.