Education groups at odds over study of Philly schools performance

Listen

(Data Visualization by Rachel Feierman/WHYY)

An influential school reform group is urging Philadelphia school leaders to approve every charter school applicant that can effectively run schools that serve a high percentage of economically disadvantaged students.

Last week, district officials heard pitches from operators hoping to open 40 new charter schools across the city.

To back up its advice on charters, Philadelphia School Advocacy Partners – an arm of the Philadelphia School Partnership – has released a report that sorts Philadelphia’s public school landscape into two systems: “high impact” and “underperforming.”

“For poor and minority students in Philadelphia, there really are two kinds of schools: those that work and those that don’t,” said the report. “Students who end up in the effective schools achieve significantly better outcomes.”

Of the 22 schools on PSAP’s “underperforming” list, 86 percent are district schools.

Of the 17 on their slate of “high-impact” schools, 70.5 percent are charters.

“The best schools serving disadvantaged students are disproportionately charters,” says the report, which calls for schools on the “underperforming” list to be closed or turned over to new managers.

PSAP’s report relies on Pennsylvania’s School Performance Profile index – a rating system which is driven almost entirely by student achievement on standardized tests.

PSAP admits the SPP has flaws.

“We note that the SPP is not a perfect tool for school evaluation; there is no perfect tool,” the report says. “But whether one uses…any other combination of assessment measures, the story is the same: there is a vast chasm between the performance of schools serving similar populations of students in Philadelphia.”

SPP issues aside, Research for Action, a Philadelphia-based non-profit education research organization, issued a stinging critique of the PSAP report, saying:

“For a study to be credible, it must meet a set of quality standards that ensure rigor, consistency, and transparency. Our examination of the PSAP document raises questions about whether the analysis meets these criteria.”

The data wars

In an interview with WHYY/NewsWorks this week, Mark Gleason, executive director of the Philadelphia School Partnership, responded to the criticism PSAP has received for its methodology. (Listen to WHYY/NewsWorks’ extended interview with Mark Gleason by clicking the play button above.)

“What I would say to Research for Action is, ‘What’s your plan to do better by these students?’ Because the evidence is plowing more money into those schools that are not getting the job done is not going to be effective,” Gleason said.

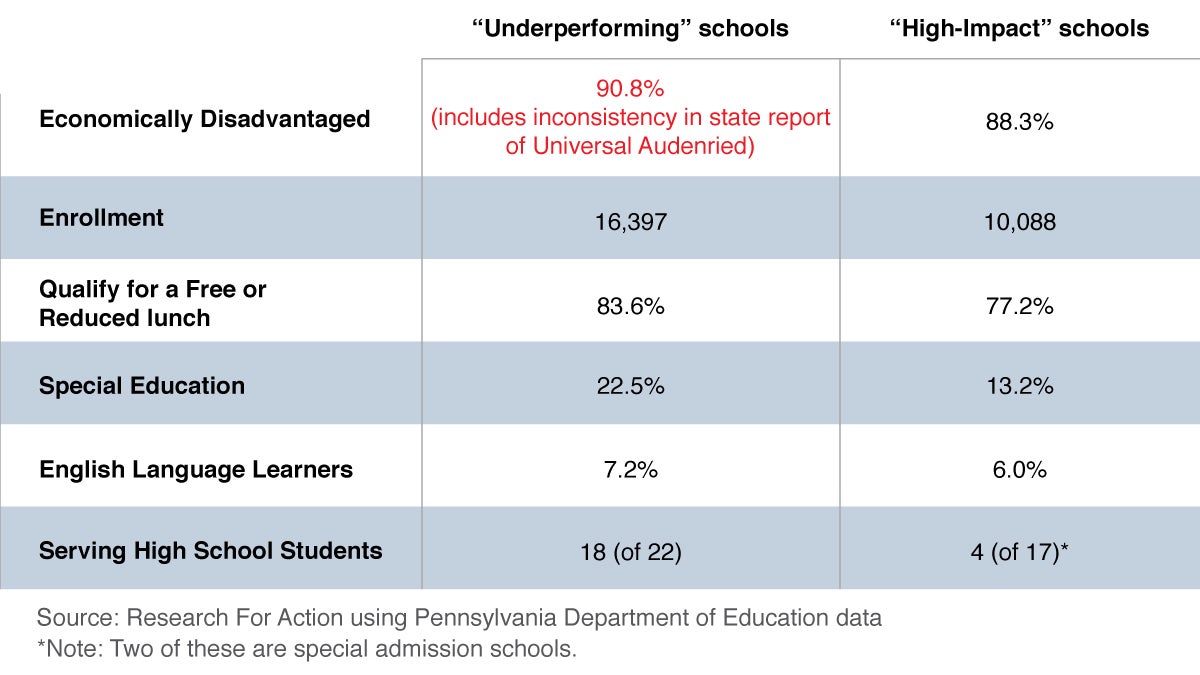

The PSAP report hinges on the idea that the schools in the two systems serve similar students, but Research for Action argues the demographic data shows that the two systems have more differences than the report assumes.

Research for Action released a reaction brief arguing that “the data presented by PSAP are not nearly sufficient to support their sweeping conclusions.”

According to state data, the 17 “high impact” schools, serve a student population that’s 73 percent black, 13 percent Latino, 88 percent economically disadvantaged, 6 percent English language learner, 13 percent special education, and 48 percent male.

The 21 “underperforming” schools serve a student population that’s 73 percent black, 15 percent Latino, 91 percent economically disadvantaged, 7 percent English language learner, 23 percent special ed, and 54 percent male.

In essence, the “underperforming” schools serve more Latino students, more low income students, more English language learners, more boys, and a resounding amount more special education students.

Gleason says that, other than the special-education data, the numbers are “not statistically significant.”

Research for Action says the difference in the poverty numbers would be more significant if not for a seeming data reporting error.

The state website on which the report relies lists Universal Audenried, a Renaissance charter, as being only 23 percent disadvantaged. In 2012-13, the school was listed as being 100% disadvantaged.

“Using the 2013-14 SPP figure dramatically deflates the percentage of economically disadvantaged students in the ‘underperforming sample,” wrote RFA authors Lucas Westmaas and John Sludden.

A spokesman for the state Department of Education said the information came from Audenried itself. Universal Audenried couldn’t be reached for comment.

If one assumes Audenried’s economically disadvantaged at 100 percent, the “underperforming” list jumps to 3.5 percentage points in that category.

RFA’s response also says PSAP’s use of special-ed data is marred by “a significant omission.”

“A more sophisticated approach would have included examination of special education rates overall, as well as data on incidence, or severity, of student needs,” Westmaas and Sludden wrote.

RFA also cites research by the Education Law Center showing that “even among special education students, charter schools tend to enroll students whose needs are less costly to accommodate.”

A June report from the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Policy Lab found that students ever involved with the Department of Human Services are concentrated in the district’s neighborhood and alternative education schools compared to traditional charters or the district’s special admission and citywide schools.

The “high impact” list also includes two selective-admission district schools and skews heavily towards elementary schools.

Also, as Research for Action points out, half of the schools on the underperforming list recently received displaced students from district schools that had been closed.

In another methodological oddity, PSAP’s report chose to disinclude The Workshop School (which PSP has funded) on the “underperforming” list because it “has existed for only one year.”

The Philadelphia Virtual Academy, which is represented on the “underperforming” list, has also only existed for one year. A spokesman for the Philadelphia School District said it’s unfair to include either new school in a broad-based comparison of SPP data.

When pressed during the studio interview about PSAP’s methodology, Gleason agreed that a wider set of factors should be considered before recommending school closures.

“Sometimes you have to leave some of the words off the page to make a point or create a document that’s actually readable,” he said. “But at the end of the day we’re not a research institution, we’re about, ‘how do we make the next step toward giving every student in Philadelphia access to a good education.'”

Gleason, though, maintained that the essence of his report was sound.

“Though Research for Action endeavors to dispute our paper’s use of demographic data, it does not dispute the paper’s central premise: that by any measure, far too many schools in Philadelphia are letting our children down,” he said in an official release.

Kate Shaw, RFA’s executive director, responded: “Our concerns about their selective use of data most certainly calls into question both their analysis and the solutions they propose.”

Gleason and PSAP declined to comment about any of RFA’s specific methodological concerns.

Of the schools on PSAP’s “high impact” list, five serve special-education populations above the state average of 16 percent: Mastery Pickett, Mastery Shoemaker, Mastery Cleveland (a Renaisance charter), Wissahickon Charter, and the district’s James Dobson elementary.

Of the schools on the “underperforming” list, two serve special-ed populations below the state average: World Communications Charter and the district-run E.W. Rhodes elementary.

New charters, the role of philanthropy and the genesis of PSP

In addition to the report, Gleason discussed a wide range of topics during the WHYY interview.

Asked how he’d to evaluate the 40 new charter applicants, Gleason said the SRC should establish a quality threshold, set the bar high and then, “approve all of the schools that clear the bar.”

Gleason acknowledged this would impact the district’s finances, but urged the SRC to “use time as the lever by which you manage financial impact … spread[ing] that impact out over three or four years.”

Speaking about how PSP judges the heated negative reaction it often receives from many traditional education advocates and teachers, Gleason said PSP was undeterred by the harsh reviews, adding, “What I can’t explain is why the criticism of our particular group tends to be so caustic and at times personal.”

PSP doesn’t just advocate; it puts significant dollars it raises from donors and philanthropies behind its favored ideas and approaches. Gleason said there was a clear need for private dollars in education on every level.

He added: “I don’t believe that we have undue access as a result of the fact that we have raised a significant amount of money. On some days, I feel like we’re the ones not getting listened to. And I think everybody in this space feels this way on different days and on different issues.”

The intention of PSP money, Gleason said, is to “create an incentive for school leaders to innovate…for school leaders to come to Philadelphia with their ideas instead of going to New Jersey or Maryland or some other place. It’s to create an incentive for the school district to shift resources to schools that need a fresh approach.”

Gleason described the genesis of PSP as a recognition among individual Philadelphia donors and foundations that their individual contributions were having only marginal citywide impact:

“We were getting some increase in the graduation rate, but other than that we were not seeing dramatic improvement on a citywide basis, and that’s what our funders want.”

Gleason listed PSP’s core funders as The William Penn Foundation, PSP board chair Mike O’Neill, the Fels Fund, The Walton Family Foundation and the Michael and Susan Dell Foundation. Gleason says PSP has about 50 donors currently “that span the ideological spectrum.”

O’Neill is the leader of the Conshohocken-based private-investment company Preferred Unlimited Inc.

“The decision was made,” Gleason said, “that if we fund together behind one organization that has a team of people that who are doing this everyday, who are evaluating schools with pretty rigorous assessment techniques, at the end of the day we have a better shot at getting a citywide impact that’s about getting students on the path to college and career readiness.”

The Philadelphia Public School Notebook contributed to this report.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.