East Market Street requires redesign

With millions of dollars being invested along Market Street east of City Hall, and a high incidence of pedestrians being struck by motorists, isn’t it time to rethink the street itself? Planner Jonas Maciunas makes the case.

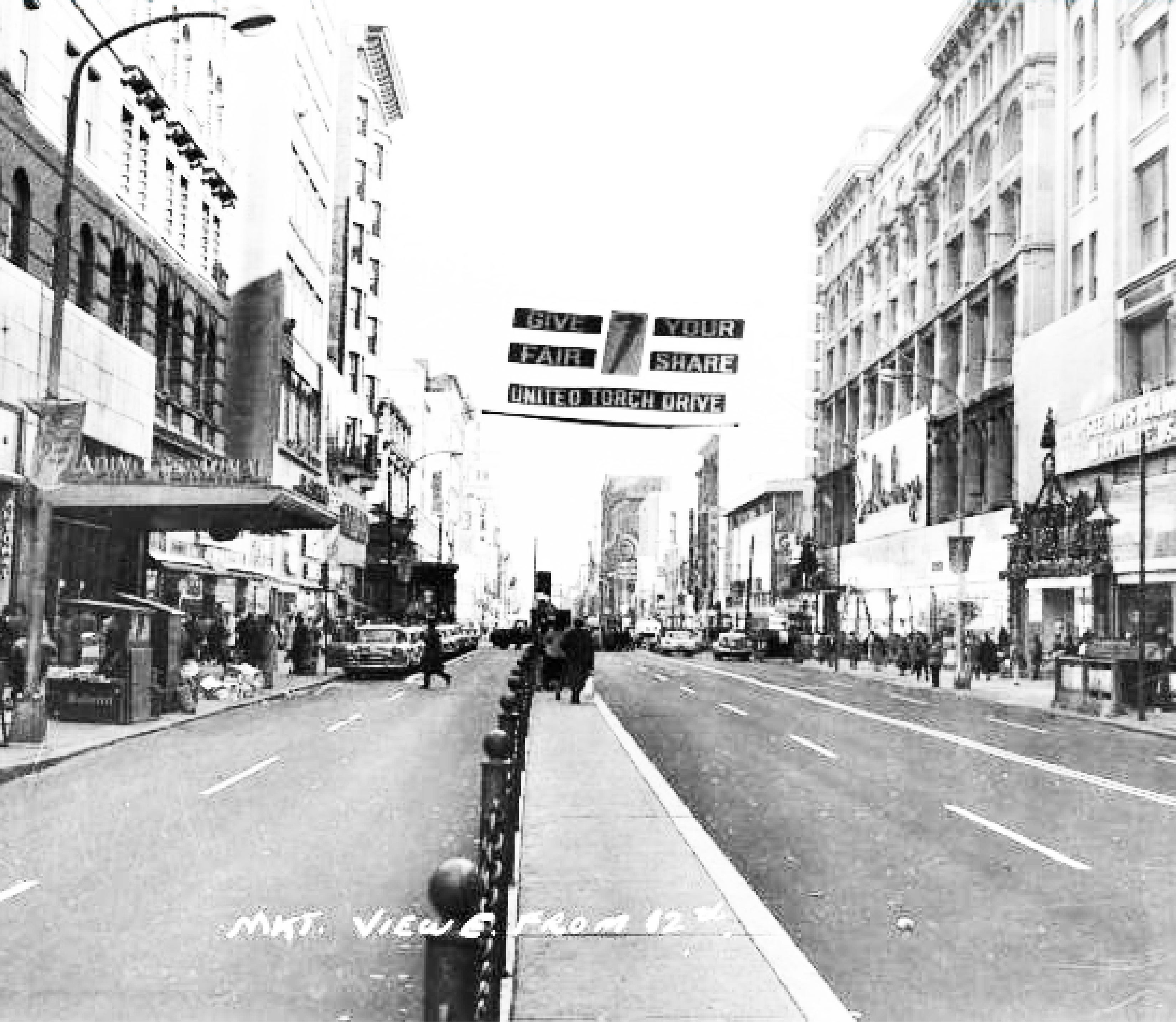

East Market Street is Philadelphia’s historic shopping district. Its east end was the city’s original port. It carried the earliest iterations of the Pennsylvania Railroad to market sheds on its center line. Philadelphia’s great department stores were born and expanded on it. Midcentury urban renewal created the iconic Gallery on its north side.

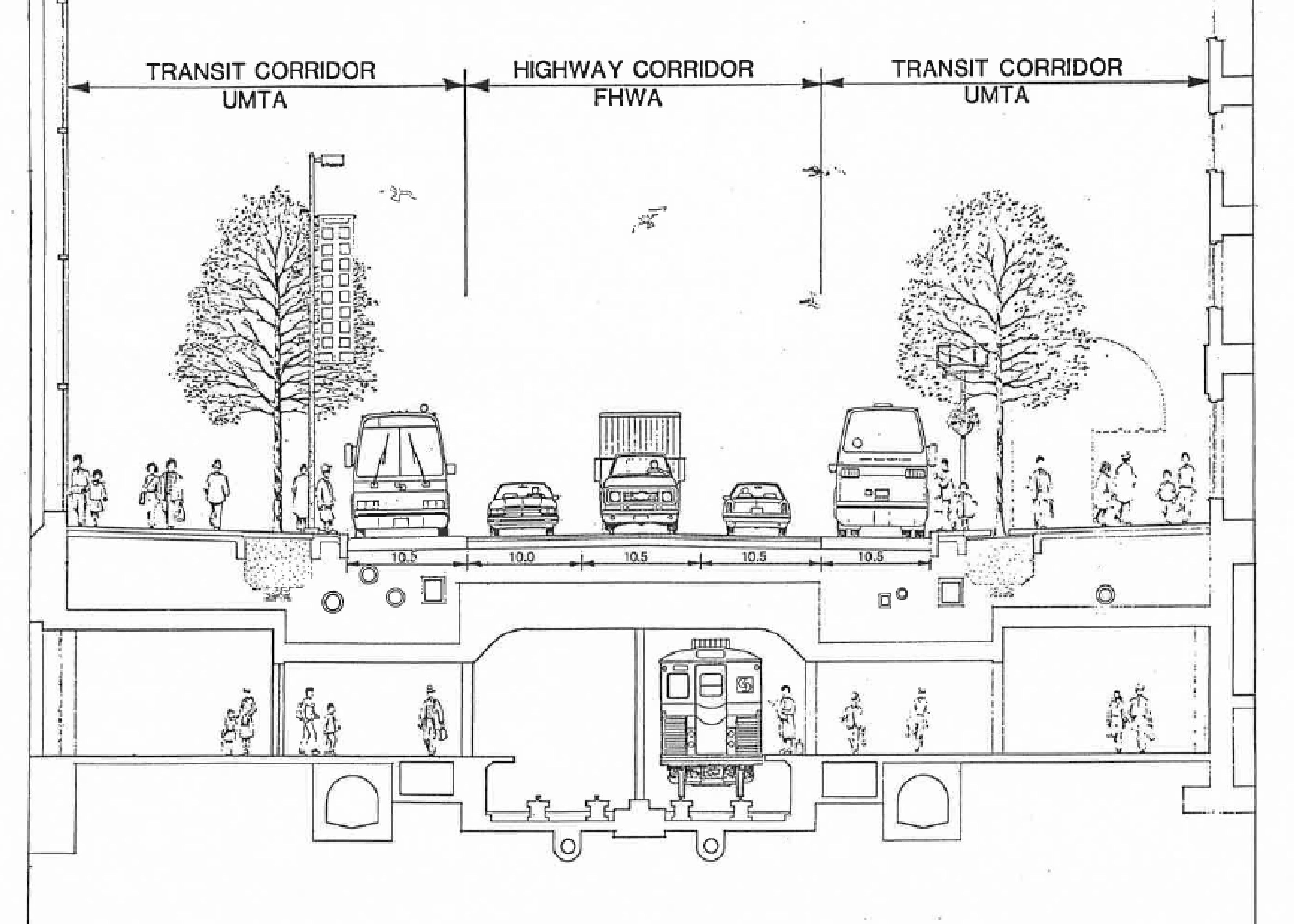

Over the course of these same generations, the physical character and organization of East Market Street itself shifted dramatically to respond to changing technology, trends, and preferences. As the 20th Century wore on, the wide sidewalks of the early department store era were narrowed to accommodate more vehicular traffic and trolley riders were moved onto floating islands in the street. Following construction of the Gallery, the Urban Mass Transit Administration and the Federal Highway Administration funded a reconstruction of the street in 1984, leading to the form we recognize today – re-widened sidewalks, a “highway corridor”, and a “transit corridor”.

Today, following some years of sluggish performance, there are new stores opening, noticeably more feet on the street, and there are big mixed-use projects rising and on the drawing board. There is more ongoing private investment than East Market Street has seen in decades. Developers predict that in five years, in addition to hundreds of new apartments, the larger format retail missing from Center City will all be here. The projects are fully leveraging the neighborhood’s transit accessibility and promoting themselves as walkable, urban developments. This is great news.

But there is also a darker story here. East Market Street, from Independence Mall to City Hall, is the most dangerous pedestrian corridor of its length in Philadelphia; from 2008 to 2013, eighty-three pedestrians were struck by motorists. That’s only the incidents reported by the Philadelphia Police Department to PennDOT, and doesn’t even begin to account for the general level of discomfort experienced by pedestrians every single day. This sort of danger and anxiety is obviously bad for individual crash victims, but is also bad for retail trade. It undermines the development projects currently underway, and will keep the neighborhood from meeting its full economic potential.

Proponents of Vision Zero say it’s time that we stop simply accepting this sort of vehicular violence as the cost of living or doing business in a major American city, and that we must shift our priorities. And make no mistake about it, public policy and street design shape transportation outcomes. By prioritizing people over their cars after an outcry about vehicular violence in the 1960s, Amsterdam has reduced traffic fatalities by 85% over the past several decades and, today, 38% of all trips in the city are made by bicycle.

Just to the east, my firm is currently completing Vision2026, a planning framework for Old City. We conducted a survey asking whether people think the neighborhood would get better or worse with more people traveling by various modes. Overwhelmingly, respondents of all groups expressed a belief that the neighborhood would get worse with more people driving, and better with more people walking, biking, and taking various modes of public transit.

Not only are preferences pronounced, but behavior also is already changing. According to DVRPC, the average daily traffic between Juniper and 8th Streets in 2013 was about 16,900 vehicles (certainly, many of them are just passing through), down from 23,700 in 1999. That decline of nearly 30% coincides with a 28% increase in SEPTA ridership and palpable surge in bicycling in the city. It goes beyond any recession-related blip and defies decades of conventional expectations by traffic engineers. A study by the Philadelphia City Planning Commission found that from 2010 to 2015, public parking inventory and occupancy have both fallen by 7% and 1.7%, respectively, even as Center City employment, dwelling, and visiting have surged. Something is changing.

If transit infrastructure, shifting preferences, and transportation trends are all pointing in a direction that supports a version of East Market Street that is safer for pedestrians and more welcoming to retail businesses, what does an alternative future look like? Consider New York City DOT’s removal of cars from transit-rich Times Square, and how successful that’s been. Fifty years ago, the Regional Plan Association suggested closing Broadway to traffic and got laughed out of the room, but by 2012 the idea’s time had come.

Toronto, a city also is in the middle of a building boom, is boldly redesigning many important streets. Front Street, right in front of Union Station, has been rebuilt as a curbless “shared space” with a single travel lane in each direction, and now functions as a market square. Queensquay, their waterfront boulevard and light rail corridor, has gone from a multilane highway with streetcars operating in mixed traffic, to a multimodal boulevard with dedicated tramways, a multi-use trail, generous pedestrian promenade, and a single travel lane in each direction. Boldest of all, the city is next planning to redesign King Street, and analog to our own East Market Street. The city’s planning director says that revisioning will include transit priority, dedicated bicycle paths, ample seating for shoppers, and possibly just a single vehicular lane, alternating directions from block-to-block, just to provide access, not space for through traffic.

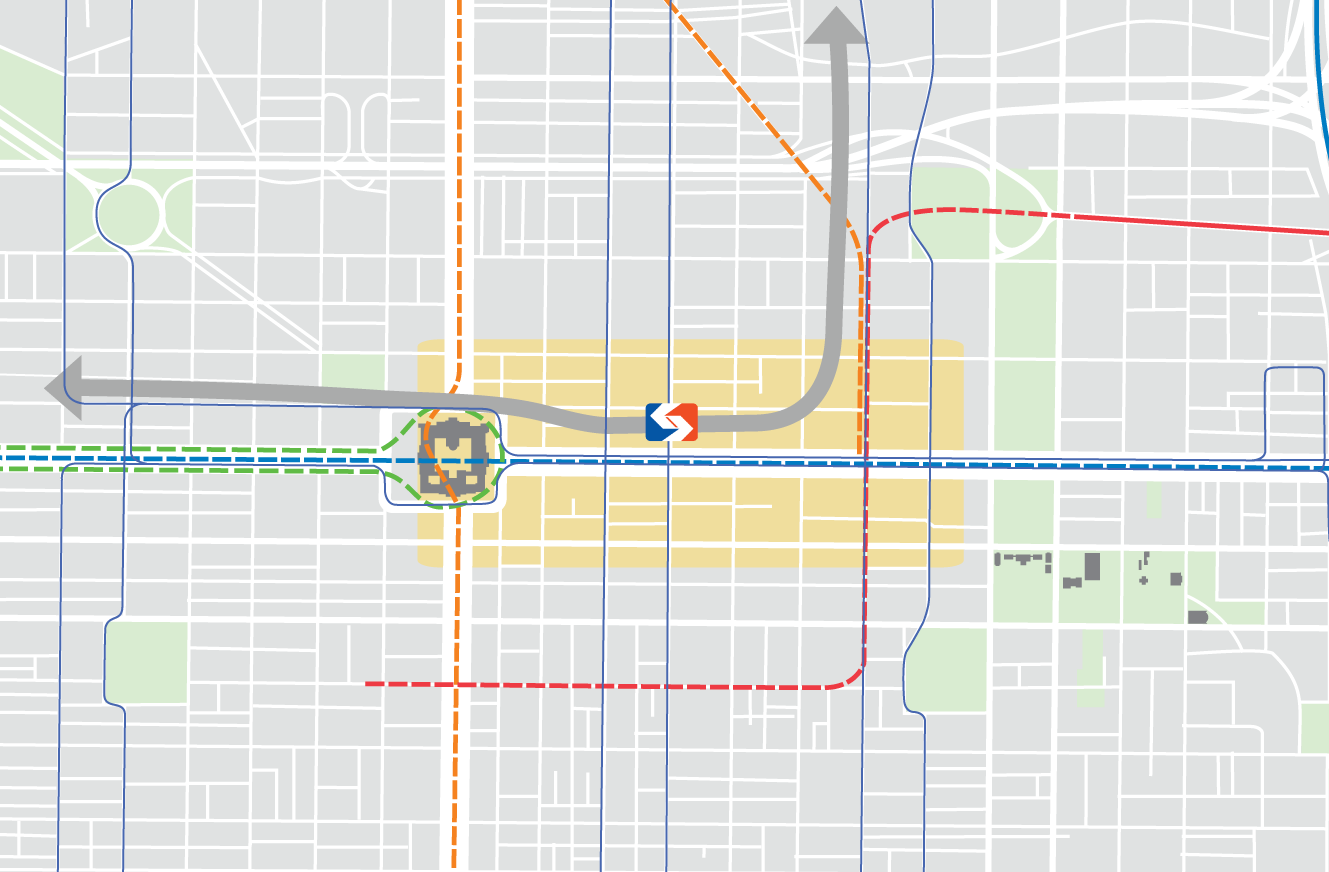

Locally, sections of Market Street are already being reimagined to the east and west. On the other side of City Hall, protected bike lanes, advocated for by Bicycle Coalition and the Center City District and designed by Parsons Brinckerhoff and Studio Bryan Haynes, would take advantage of excessive roadway and provide space for safe cycling. On far East Market Street, Old City Vision2026 is recommending the transformation of the 200 block of Market Street into a curbless, shared-space station plaza for the subway, complete with parking-protected bike lanes, enhanced transit shelters, and slow travel lanes. Neither of these are necessarily right for East Market, but the question becomes – between Old City and Market West, will we take a fresh look at how Philadelphia’s Main Street functions?

Market Street has evolved over the generations to meet the technology, trends, and preferences of its time. In the 1860s, it was largely unpaved, carried the Pennsylvania Railroad, and included market sheds at its center. Now as then, change is hard, and requires funding, trade-offs among multiple priorities, and creative design solutions. But could you imagine if, through the 20th Century, we had not risen to that challenge and kept a roadway designed for an obsolete 19th Century transportation system?

East Market Street was designed in 1984 and no longer serves the needs of our city or the preferences of the market. Not only does it create an unsafe pedestrian environment, constraining the economic potential of the district, but it provides no enduring pleasure. Philadelphia’s “main street” should be a joy to stroll along. Amid the ongoing surge of private investment, the time has come to take a hard look at the priorities of the public realm on East Market Street.

For additional images and context, head over to Jonas Maciunas’ blog.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.