Drugs detected in private well water in north central Pennsylvania

Simply put, drugs leave the body and go down the toilet. There are similar types of drugs in similar concentrations in water in Canada, the U.S., and most of Europe.

(Bigstock/Satura)

Researchers at Penn State University recently found small amounts of over-the-counter and prescription drugs in well water in rural north central Pennsylvania.

The substances include antibiotics for treating bacterial infections and the common painkiller acetaminophen.

Joanna Wilson, a biologist at McMaster University in Canada who was not part of the study, said she’s not surprised at the findings.

“Pretty much everything that’s used in the human population at a high rate can be found in the environment,” she said. “Often people don’t really think about the medication that they’re taking and where it goes; they see it going into their body, but they don’t think about it coming out.”

Simply put, the drugs leave the body and go into the toilet. And some still get rid of extra prescriptions by flushing them down the toilet.

There are similar types of drugs in similar concentrations in water in Canada, the U.S., and most of Europe, she said.

These drugs are found in very low concentrations, so low that we shouldn’t have to worry about significant health risks to humans, said Heather Gall, one of the researchers and an assistant professor of agricultural and biological engineering at Penn State.

“You would have to drink hundreds of thousands — if not millions — of liters of water to get the equivalent of a dose of one of these contaminants,” she said.

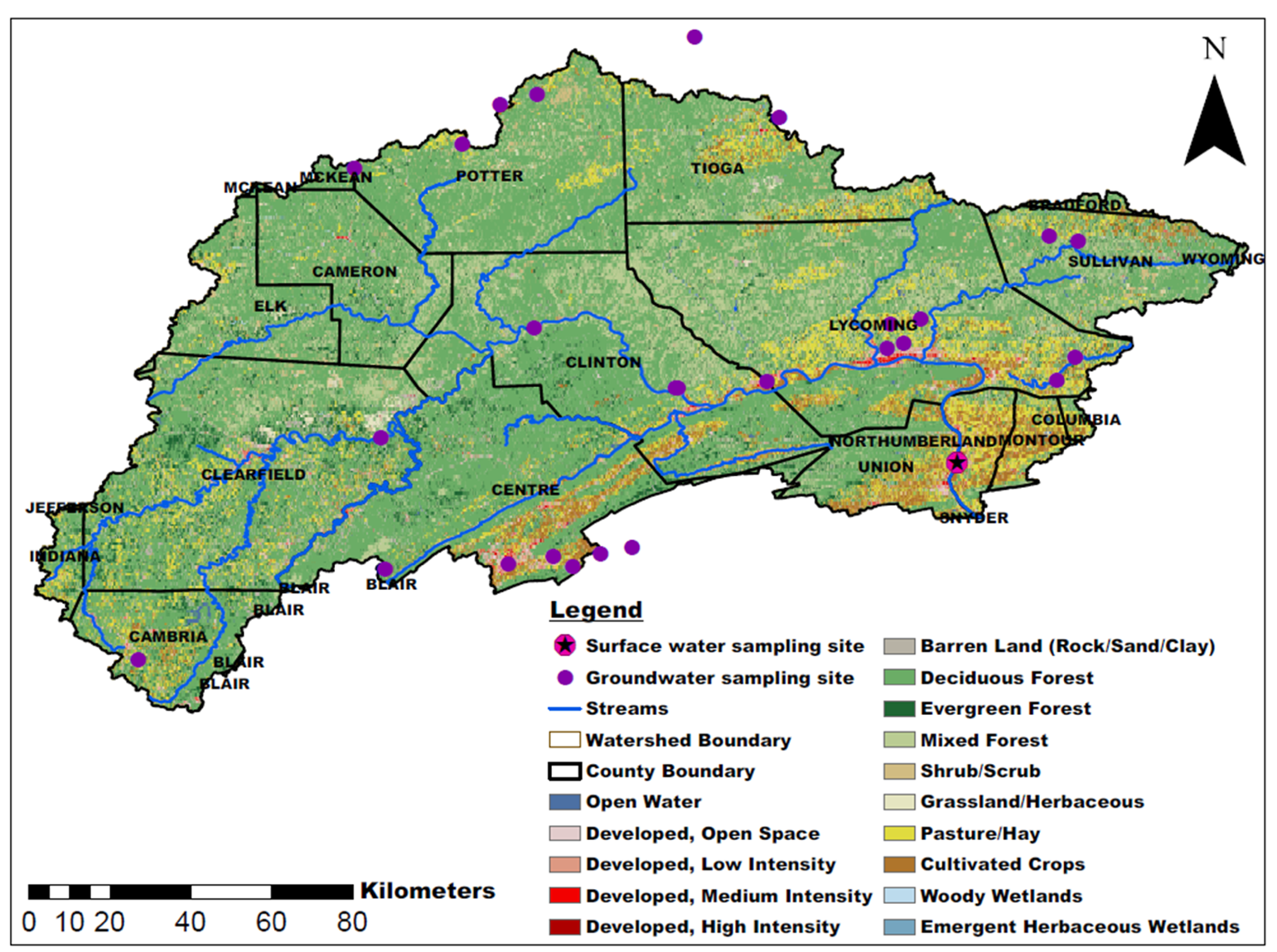

When her team told the well owners of their findings, she said, they wanted to know the origin of the drugs. The wells are in rural, forested areas, so the drugs probably didn’t come from agriculture runoff or wastewater.

Gall, who said her team doesn’t have a definite answer, said it’s likely the drugs came from a septic tank leaching into the groundwater that feeds the wells.

The team also has been testing samples from public drinking water in the same area over two years, and it expects to have results of that work soon.

Though the weak concentration means the drugs should pose no danger to humans, Wilson said they can affect fish and other things in the water.

For example, she found in her research that zebrafish embryos exposed to the painkiller acetaminophen are more likely to have developmental abnormalities, which would most likely kill them in the wild.

One drug that does worry Wilson is carbamazepine, which is used to treat patients with epilepsy. It is not removed during wastewater treatment and remains stable in water, she said, so it can travel far. As reported in Ars Technica, a 2016 study found that carbamazepine can accumulate in crops irrigated with treated sewage — and then end up in the urine of people who don’t use the drugs but eat the produce.

Still to be determined is what happens to humans who drink water with these low levels of different drugs mixed together over a very long time.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.