Dolphin deaths continue off the New Jersey coast

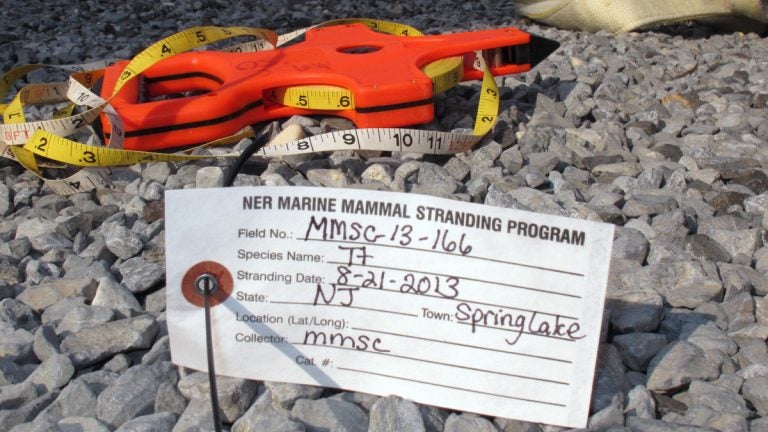

This Wednesday, Aug. 21, 2013 photo shows an identification tag, the equivalent of a dolphin toe tag for a dolphin that had died on the Spring Lake N.J. beach. (AP Photo/Wayne Parry)

Everyone who has been following this year’s stranding epidemic knows that New Jersey’s dolphins had a tough summer. This week, NOAA Fisheries Regional Marine Mammal Response Coordinator Mendy Garron confirmed that dolphin deaths in the New Jersey region have continued into the fall.

Morbillivirus outbreak continues

Researchers agree that the primary cause of this year’s Unusual Mortality Event (UME) among bottlenose dolphins, as defined by the 1972 federal Marine Mammal Protection Act, is an illness known as morbillivirus. Many of the dead and dying animals that have washed up on New York, New Jersey, Delaware and Virginia beaches this year have lesions of the skin, mouth, or lungs.

Garron, who oversees stranding response programs among many non-government partners from Maine to Virginia, said that while New York strandings seem to have tapered off, dolphins testing positive for morbillivirus are now starting to appear on North and South Carolina beaches. So far this year, from New York to North Carolina, over 800 stranded dolphins were counted between January 1 and October 21. That’s many times the typical average.

Dolphins still stranding in New Jersey

“We’re still seeing a large number of animals in Virginia and up through New Jersey,” Garron said, speaking with NewsWorks by phone last week.

According to updated numbers released by NOAA on October 21st, the total number of bottlenose dolphin strandings in Virginia since July has topped 300, while in New Jersey, the second-most active site for the strandings, that number approaches 150. In October alone, as of the 21st, New Jersey saw over 20 stranded dolphins.

In 1987-88, scientists attributed a similar UME to morbillivirus, but the number of strandings this time around has been a bit higher. Garron said that a total of 700 animals were recorded in that UME between New York and Florida, but the current outbreak passed that number in July.

A changing migration

However, Garron explained that the autumn dolphin deaths in our region are not necessarily an indicator that the virus is having a more severe impact this time around. The dolphins’ range has been expanding and, for a variety of factors that scientists are still studying, many dolphins have delayed their southward winter migration in recent years, with some even choosing to winter in New Jersey’s salty coastal rivers.

“What we’re seeing is that animals are remaining farther north for a longer period of time,” Garron said.

This means that while there have been many more strandings in New Jersey and Virginia than there were in the previous outbreak, this is probably because the dolphin population is staying in that region for a greater part of the year, compared to the late eighties. Back then, the deaths “were a little more evenly distributed throughout the states.”

Pressing questions

Garron said the science of why the dolphins’ migration timetable is shifting is still in its infancy, but climate change and shifting feeding patterns could be factors. She added that right now, the mid-Atlantic crisis is one of six marine mammal UMEs nation-wide.

“We’re seeing a lot of different stranding trends right now, and I think there are a lot of questions out there that need to be answered.”

Even if the die-offs in our region do taper off as the dolphins move south later in the year, and a greater number of surviving animals build an immunity to the virus, NOAA’s work to understand the outbreak is just beginning, despite challenging cuts in federal funding.

“What we’re doing now is starting to look at some of the secondary infections,” Garron explained. “When animals have a virus like this, they’re susceptible to other pathogens.” This means that some washed-up dolphins, though they may test positive for morbillivirus, may not have been killed by it. A secondary fungal or bacterial infection, like pneumonia, could have been the fatal blow.

A damaged life cycle?

But figuring out exactly what is killing the dolphins now is only one part of the picture that will unfold in the years to come.

“Unfortunately we have such a high level of mortalities now, I think a bigger question is how that’s going to impact the population,” Garron said. With so many animals affected, there may be a corresponding drop in the population’s capacity to reproduce.

“So even if the strandings stop,” Garron emphasized, “there’s a lot to keep track of.”

Stranding partners

Fortunately, NOAA has the help of a large network of non-governmental stranding partners across the east coast.

“I can’t speak highly enough of them,” Garron praised. Particularly during the partial shutdown of the federal government earlier this month, Garron said NOAA’s stranding partners were able to continue the important work of tracking the dolphin deaths: “They’ve done a tremendous job in responding to this event.”

One of these partners is the Brigantine, N.J.-based Marine Mammal Stranding Center, which is offering nearby coastal dwellers a chance to get involved. On November 9 at 9 a.m., the Stranding Center is hosting a stranding volunteer workshop at Jenkinson’s Pavilion in Point Pleasant. A limited number of participants will learn “first responder” skills for stranded marine mammals and sea turtles in New Jersey. Prospective volunteers must be at least 18 years old and live within fifteen minutes of the beach or coastal waterway.

To sign up or get more information, contact the Stranding Center’s Sarah Miele at 609-266-0538 or edummsc@aol.com.

And for anyone on the beach this fall or winter, it’s important to report stranded sea life as soon as you see it, without approaching the animal yourself.

“We’re still monitoring this and we’re still collecting data on this event, so that reporting is very important,” Garron said. Anyone who spots a stranded dolphin should call the Northeast’s marine mammal stranding network at 1-866-755-6622.

Latest NOAA data.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.