Does Philly’s ban on cashless stores still leave ‘unbanked’ residents behind?

Philadelphia is the first major city to ban cashless stores. But anti-poverty advocates and low-income residents never asked for it.

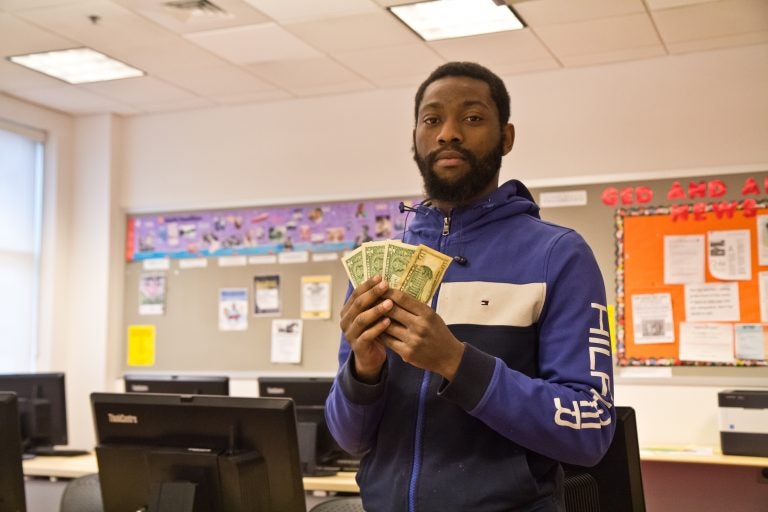

Dwight Tindal works in demolition and is unbanked. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

Back in December, Philadelphia City Council passed “Fair Workweek” legislation, joining a growing national movement aimed at giving retail and fast-food workers more predictable schedules.

New York, San Francisco, and Seattle have similar laws, in no small part because low-income residents and unions lobbied lawmakers and put the issue on their radar.

That’s typically how it works. Advocates shine a light on a problem. A bill gets introduced.

The roots of a new law in Philadelphia are very different. They trace back to one man: City Councilman Bill Greenlee.

Last fall, he introduced a bill outlawing “cashless” businesses — brick-and-mortar shops and restaurants where customers can only pay with credit and debit cards or an app.

Mayor Jim Kenney signed it last week, making Philadelphia the first major city in the country to ban cash-free stores. It takes effect July 1.

“I heard that there started to be some establishments in Center City. Something just didn’t sit right with me on that,” said Greenlee.

The veteran lawmaker thought it was discriminatory for these businesses to turn away low-income residents who don’t have bank accounts, a population collectively referred to as the “unbanked.”

“It just seems unfair to have that separation. It’s almost like it’s ‘us’ and ‘them,’” said Greenlee.

Nearly 13 percent of Philadelphia’s population — about 200,000 people — are unbanked, according to federal banking data. That’s more than double the regional average.

Construction worker Dwight Tindal is one of them. He had a bank account a few years ago. He closed it because his balance never stayed above zero for very long.

“I got a little baby — a son. And bills, too. So that go to all that,” said Tindal.

The 24-year-old only uses cash, keeping his money at home in a secret location. He counts his stash two or three times a day, every day, and only takes out what he knows he needs. The rest stays hidden.

It’s a stressful system, Tindal said, especially when he starts thinking about someone robbing his family’s house in North Philadelphia.

“I’m concerned every day, even if I don’t think it’s going to happen. I just think, ‘Dang, I should move it here’ or ‘I should move it over here,’” said Tindal.

Still, he said he’s not offended by the handful of businesses in the city that only accept cards, including the fast-casual chains Sweetgreen and Bluestone Lane.

A Sweetgreen spokesman declined comment on Philadelphia’s new law. Nicholas Stone, founder and CEO of Bluestone Lane did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

In an interview last year, Stone told NPR he made Bluestone cash-free because the overwhelming majority of the company’s customers never paid in cash. Stone also said lines move faster when employees don’t have to make change for customers who pay in cash.

The Chamber of Commerce for Greater Philadelphia opposed the bill, complaining in a letter to City Council that banning cashless businesses might discourage local entrepreneurs from setting up shop in the city.

“Passing such a measure will allow local government to dictate how entrepreneurial business owners will operate versus customers deciding not to shop there,” wrote president Rob Wonderling.

Amazon also lobbied against the bill, saying it would reconsider its plans to bring one of its new cashless “Amazon Go” stores to the city.

The measure still sailed through City Council. In about six months, Philadelphia was leading a national trend.

New Jersey needs the governor’s signature to join Massachusetts as the only states to ban cashless businesses. New York and San Francisco, two cities that each have dozens of cash-free businesses, are considering similar legislation.

‘Philadelphia is not an island’

Yet, anti-poverty advocates in Philadelphia, even ones that support the legislation, said cashless businesses weren’t a concern before Greenlee introduced his bill.

Otis Bullock is executive director of Diversified Community Services, a social service agency in Point Breeze. He thinks City Council missed the mark by not focusing on legislation to help more people like Dwight Tindal get on stable financial footing.

“I would have liked to see a measure that more directly impacted poor people as far as getting them out of poverty,” Bullock said. “You know, a measure that raises their income, or, at a minimum, a measure that addresses the actual issue, which is those who experience financial insecurity becoming unbankable.”

Greenlee admits the genesis of his bill was unconventional. He sees value in it nonetheless because of the impact it could have as the cashless trend grows.

“If there comes a time in a few years where everybody has the same ability to use some kind of credit, debit, plastic in some way, then fine, maybe this law wouldn’t be necessary anymore,” he said. “But that’s not the case now.”

The law forces existing cashless businesses to change course, but also stops new ones from going that route in the future.

Kerry Smith, a staff attorney with Community Legal Services, said that safeguard is critical, especially when it comes to retailers of staple items, such as toiletries and food.

“If there’s a trend where those kinds of companies are turning away people for not having cash, that’s going to have a significant impact on low-income individuals in Philadelphia,” Smith said.

Other advocates argue the arrival of businesses like Amazon Go should spur a deeper conversation about financial literacy for the unbanked.

Will Gonzalez, executive director of Ceiba, a nonprofit that fights poverty in the Latino community, said government needs to “empower people for the future,” not protect them from it.

“The reality is that we’re in the digital age,” Gonzalez said. “The digital economy is going to grow and Philadelphia is not an island.”

This article is part of Broke in Philly, a collaborative reporting project among 22 news organizations, focused on Philadelphia’s push towards economic justice. Read more of our reporting at brokeinphilly.org.

This article is part of Broke in Philly, a collaborative reporting project among 22 news organizations, focused on Philadelphia’s push towards economic justice. Read more of our reporting at brokeinphilly.org.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.