Despite gains, southeastern Pa. lags in reducing hospital readmissions

Photo via ShutterStock) " title="sscopdx1200" width="1" height="1"/>

Photo via ShutterStock) " title="sscopdx1200" width="1" height="1"/>

Hospital readmissions for congestive heart failure and diabetes were highest in Pennsylvania among the youngest adults, aged 18 to 44. (Photo via ShutterStock)

Too often, leaving a hospital is not the success story doctors, nurses and patients think it might be. Patients frequently return just weeks later — sometimes for the same condition.

“Patients are falling through the cracks,” said Joe Martin, the executive director of the Pennsylvania Health Care Cost Containment Council, the agency keeping tabs on hospital readmissions across the state. “There isn’t proper follow-up.”

While not every readmission can be prevented, a low rate is one marker of high quality care — and an important way to save money.

In a report released on Wednesday, the council found Pennsylvania hospitals have improved over the last several years, with fewer patients returning for congestive heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) within 30 days of the original stay. There was no change in readmission rates for the state as a whole for two other common conditions, abnormal heartbeat and diabetes.

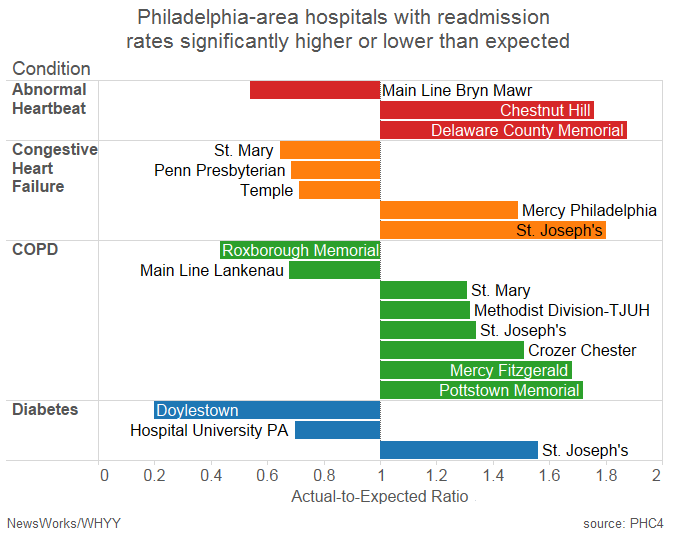

Although southeastern Pennsylvania hospitals are moving in the right direction, the region is still the highest in the state for readmissions in three of the four condition categories studied. In particular, St. Joseph’s in North Philadelphia had higher than expected readmission rates for congestive heart failure, COPD, and diabetes. The hospital did not return repeated calls for comment.

Doylestown Hospital, however, can boast of as many as five times fewer readmissions than expected for diabetes treatment. Other high performers include Main Line Bryn Mawr for abnormal heartbeat; St. Mary, Penn Presbyterian and Temple for congestive heart failure; Roxborough Memorial and Main Line Lankenau for COPD; and Hospital University PA for diabetes.

Some of those successes are in part due to incentives from the government, said Cristina Boccuti of the Kaiser Family Foundation. Beginning with the 2013 fiscal year, hospitals with high readmission rates faced reductions in their Medicare payments.

“Hospitals are clarifying patient discharge instructions,” she said. “They’re also coordinating with post-acute care providers. And hospitals may be conducting more follow-up with the patient’s primary care physician.”

Another option many providers are trying, said Priscilla Koutsouradis of the Delaware Valley Healthcare Council, which represents area hospitals, is the “teach back” technique.

“They ask the patient to play back what they’ve learned to ensure that that really crucial communication has indeed taken place,” she said.

The readmission rates were controlled for severity of illness, age, and gender, but not for socioeconomic status, which could be one reason why some Philadelphia-area hospitals fare poorly on the measure, said Koutsouradis. Across the state, readmissions were consistently higher for people insured through Medicaid.

The data also revealed a disturbing snapshot of rehospitalization for younger adults. For both congestive heart failure and diabetes, patients aged 18 to 44 years old were most likely to be readmitted, not the elderly.

“I think it reflects an unfortunate trend where we see some of these disease categories affecting younger and younger people,” said Martin. “We’ve seen the obesity problem drifting further and further into the younger populations. We see that with diabetes, and we see that with asthma.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.