Delaware museum looks back at racism, tumult of ’68 — and shadows still stretching over Wilmington

For the fifty-year anniversary of the Wilmington military occupation, the Delaware Art Museum examines how the past reaches its tendrils into the present.

Listen 4:58

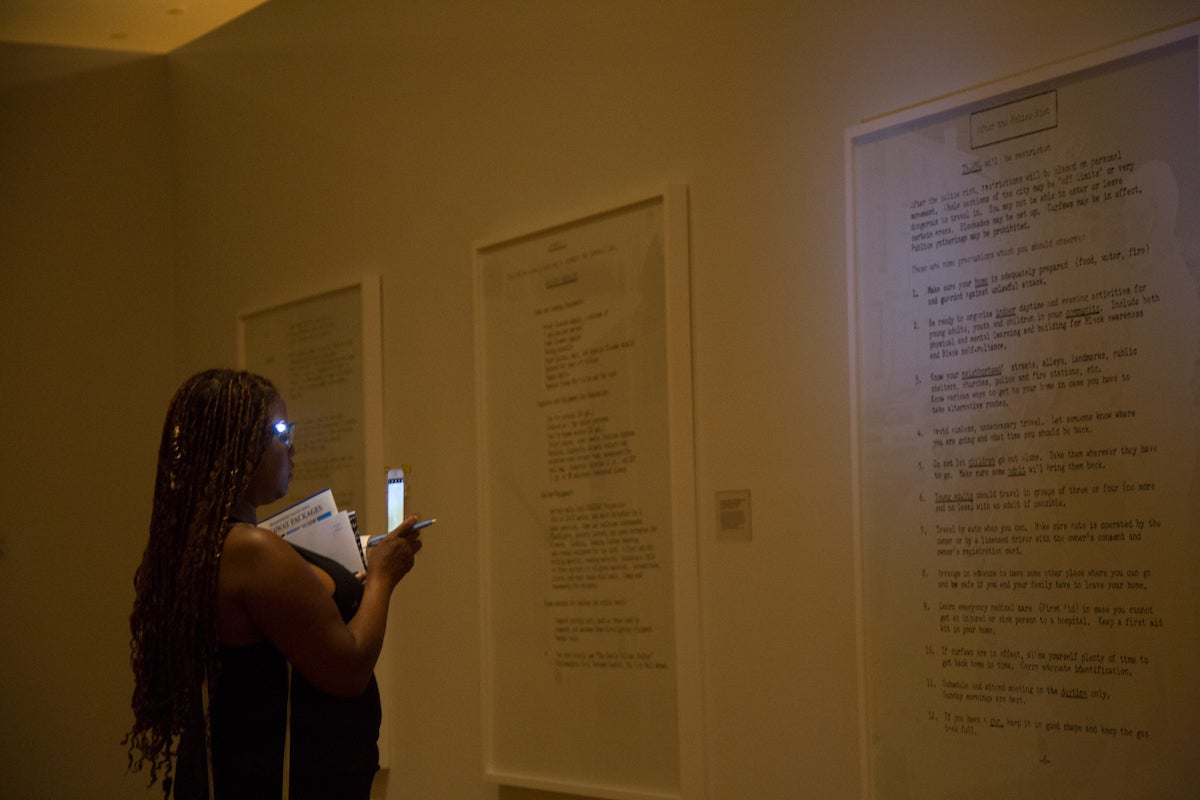

Image from "Black Survival Guide, or How to Live Through a Police Riot" courtesy of the Delaware Museum of Art.

“IMPORTANT” begins the text of a new exhibition by Hank Willis Thomas at the Delaware Art Museum. “Because you are black, this book is important to you. It may save your life.”

It’s a striking start to a striking exhibition that should be experienced in person. How you view the images changes what you see.

“The activation is rooted physically in your body,” said curator Margaret Winslow. “Conceptually, I think what that gets to is the subjectivity with which we view every moment, every interaction, the present, and the past.”

And this is a show all about the shifting past — and its tendrils reaching into the present.

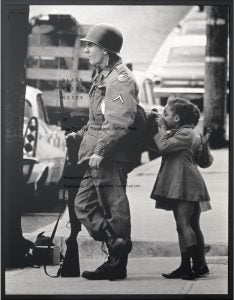

Thomas was commissioned by the Delaware Art Museum to create a piece that responds to the legacy of Wilmington’s 1968 unrest. After Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination that April, cities across the country erupted in displays of anger and pain that went on for weeks. Wilmington was no different, but Gov. Charles Terry’s response was: He declared a state of emergency and called in the National Guard. For nine months, troops and tanks remained in the city, enforcing a nightly curfew. It is still the longest military occupation of a U.S. city since the Civil War.

“It felt like Gov. Terry was trying to make Wilmington into Montgomery, Alabama, or Mobile, Alabama, or Little Rock, Arkansas,” said Billie Travalini, a writer who was in high school in Wilmington in 1968. As far as she could tell, the troops only made things worse.

“Gov. Terry’s actions took the soul out of the city. He robbed the city of a chance of natural healing. He took a machete to open an apple,” she said. Even then, she saw the tanks as a means of control. “But he wasn’t just controlling blacks, he was controlling whites [too]. He was robbing them of the opportunity to have a full community.”

Now, 50 years after the unrest and the occupation, the Delaware Art Museum has been convening conversations about the meaning of that legacy for Wilmington. The museum is hosting storytelling sessions where people can share their memories of that year; it’s holding community forums about contemporary issues related to race and policing. And it’s commissioned this piece by Thomas, titled “Black Survival Guide, or How to Live Through A Police Riot.”

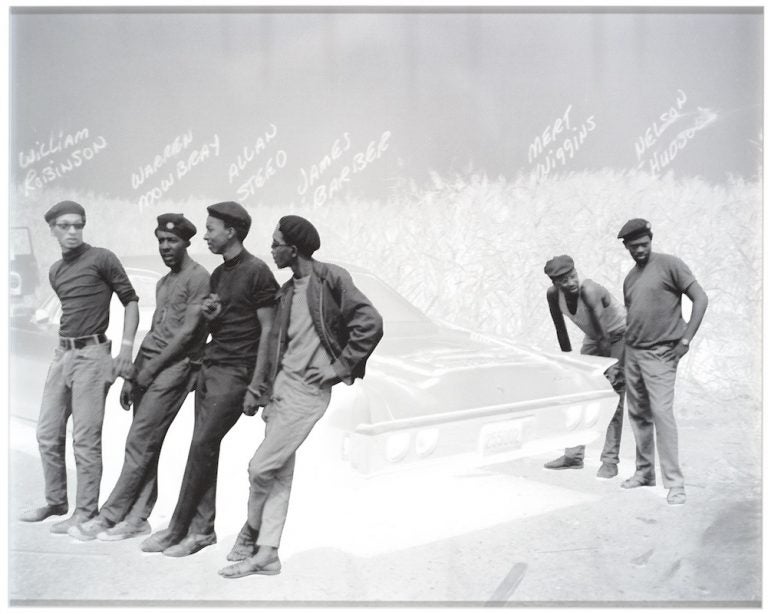

In it, the artist has layered two artifacts of that tumultuous era: photographs from a recently rediscovered archive of images from Wilmington’s News Journal and a pamphlet he found while digging in archives of the Delaware Historical Society. Circulated by a neighborhood group in Wilmington in 1968, the Black Survival Guide is “a step-by-step handbook someone had made to provide really needed critical information to people who might find themselves in a police occupation,” said Thomas.

It’s filled with practical details: how much water to stockpile, how to stanch heavy bleeding, what to do when the electricity goes out. It’s reminiscent of “green books,” which helped black travelers safely navigate hotels, restaurants, and other establishments during Jim Crow. Some of the other information in the pamphlet was culled directly from contemporary texts about surviving a nuclear attack.

“History books can only capture but so much, a single photograph can only capture but so much,” says Thomas. “But to read a document like this, you almost have to put yourself in the mind frame of the people that made it. Meaning, the sense of urgency that it was made of.”

For the show, Thomas blew up pages from the pamphlet, layered them with photographs of the occupation, and screen-printed the composite images on a reflective material, the same kind used for highway signs. To the naked eye, only the pamphlet pages and a ghostly trace of the photographs are visible. When visitors shine a light directly on the images — you can use your phone, or the museum provides special glasses with little flashlights mounted on the sides — photographs of protesters and troops and firefighters emerge, dazzlingly bright. It’s a disorienting experience, like walking through a cloud of smoke.

“I studied photography, and I’ve always been fascinated especially with the experience in the dark room, where an image sort of appears before your eyes,” says Willis Thomas. “My hope with this work is that viewers of the images and the text have a revelation, a visual revelation, walking through the exhibition.”

They may have a personal revelation too. Ti Hall, the museum’s manager of communications and storytelling, says she continues to be struck by how relevant some of this information remains.

“I’ve been through this exhibition several times, and each time I find myself just reading each page, and reading each page, and soaking it in. I’m the parent of a soon to be 20-year-old African-American son, and I find myself wondering how much of this I need to teach him in order to be able to navigate this world,” she said.

“Black Survival Guide or How to Live Through a Police Riot” is on view until Sept. 30. The Delaware Art Museum has two other exhibitions reflecting on 1968 on view until Sept. 8: Danny Lyon: Memories Of The Southern Civil Rights Movement, a photography exhibition, and The Montgomery Bus Boycott: Drawings By Harvey Dinnerstein and Burton Silverman. And it’s partnered with the Delaware Historical Society to create this website about that fateful year.

Here are all the other events linked to this exhibition. All are free.

Share your story

July 26, Aug. 2 and 16, 4–8 p.m.

In partnership with University of Delaware’s Creative Writing Students, anyone is invited to share their personal experience of the Wilmington occupation.

Community Forums

July 26, Aug. 2 and 23, 6 p.m.

Community organizations are bringing the present into the past with a series of public forums about racial and social justice, civil rights, and education.

Performances

Jaamil Kosoko, Aug. 9, 6 p.m.

TAHIRA and Jea Street, Aug. 19, 1 p.m.

Ashley Davis and Terrance Vann, Sept. 16, 1 p.m.

These original performances by local and regional artists all respond to the unrest and occupation in Wilmington through music, visual arts, dance and storytelling. Two of the performances are collaborations between artists working in different disciplines: musician Jea Street with storyteller TAHIRA, and dancer Ashley Davis with visual artist Terrance Vann. Jaamil Kosoko is performing at the museum as part of a two-week residency.

For Freedoms Town Hall: Restorative Schools Issue Campaign

Sept. 26, 5:30–8 p.m.

Kingswood Community Center

In partnership with Network Delaware, the museum is holding a town hall discussion about the Restorative Schools Issue Campaign. The artist and For Freedoms co-founder Hank Willis Thomas will moderate a panel of community residents, organizers, practitioners, and scholars talking about race, schooling, and law.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.