Critics of Delaware's school funding system call for overhaul

The ACLU suit says the system discriminates against students who are poor, disabled or learning English because it doesn’t provide the extra funding they need to succeed.

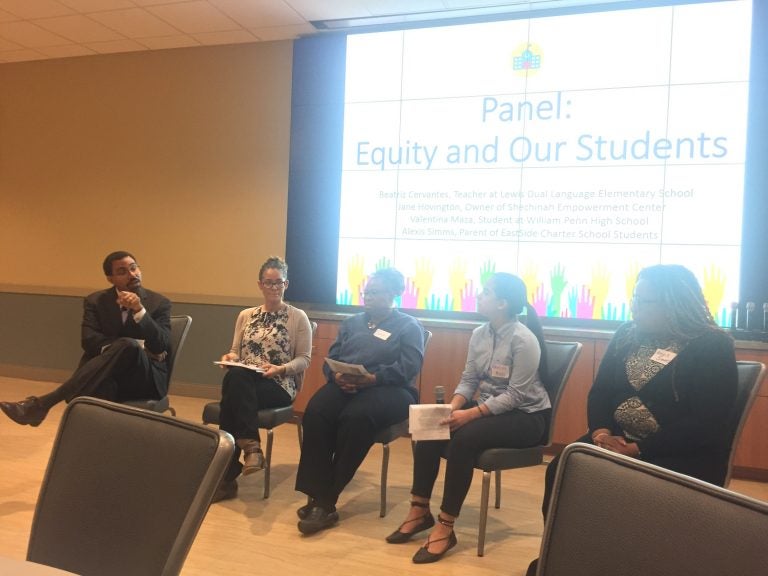

Former U.S. Education Secretary John B. King Jr. (left) holds a panel discussion about funding disparities in Delaware schools during a summit this week near Newark. (Cris Barrish/WHYY)

A clarion call is being sounded in some Delaware education circles to revamp the way public schools are funded.

The American Civil Liberties Union of Delaware sued the state in January, arguing the current system is unconstitutional. At a conference this week, local and national leaders piggybacked on that theme and advocated change.

The ACLU suit says the system discriminates against students who are poor, disabled or learning English because it doesn’t provide the extra funding they need to succeed. Many say that disparity is a main cause for the achievement gap between low-income and affluent kids.

So about 100 reform-minded educators and business leaders held the Delaware Education Funding Summit near Newark this week to explore ways to make improvements as soon as possible.

The keynote speaker was John B. King Jr., who led the U.S. Department of Education for the last year of Barack Obama’s presidency. King said the state’s future is at stake.

“Delaware is a place where there’s low unemployment. There’s new employers coming to the state. That’s good,’’ King told WHYY after delivering remarks and hosting a panel discussion with attendees.

“But that won’t continue if there’s not an educated workforce ready to take those jobs, whether it’s in tech or the STEM field or health sciences. We have to make sure the next generation is ready to be competitive. But if we don’t invest, particularly in our low-income communities, then those businesses will go overseas” or to other states.

Delaware spends about $2 billion a year in state, local and federal funds to educate about 138,000 kindergarten through 12th grade public school students. It spends an average of $14,120 per student, the 12th highest amount in the nation, federal statistics show.

But critics and the ACLU lawsuit say the average is misleading, because the money is distributed inequitably.

Rather than the $14,120 being allocated to each student, regardless of where he or she attends school, the money is allocated based on the number of teaching units in each school. That means more money goes to schools and districts where there are veteran, higher-paid teachers who often gravitate to better-performing schools in more affluent districts.

Denver-based education consultant Mike Griffith told WHYY that Delaware’s 1950s-era system is too antiquated.

“It wasn’t designed for an age where we know that we want students to achieve at a higher level, when we want to connect funding to student achievement,’’ said Griffith, a finance expert with the Education Commission of the States.

“What you have tried to do over the last 70 years is essentially jury-rig your system to take some of that stuff into account.”

Griffith acknowledged that fear of the unknown, especially that teaching jobs could be lost, could delay any overhaul of the funding system in Delaware, as it has in other states.

“There’s nervousness,’’ he said. “But we found that you usually have the same number of teachers.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.