Violent crime is down in Norristown, but its unsafe reputation remains

Listen 5:31

Doris Smith Starks heads up the Norristown Town Watch and is pleased with the recent push for 'community policing' in the borough. (Laura Benshoff/WHYY)

“I wouldn’t live in Norristown for all the money in the world,” said Chuck Rutledge, as he sat in his wheelchair, smoking a cigarette in front of the county administration building on Swede Street.

The Montgomeryville resident lived here “years and years and years ago,” but said he left because there was too much crime.

Start a conversation about Norristown, which sits about 20 miles northwest of Philadelphia, and you’re likely to get emphatic responses. While the borough has its boosters, the Montgomery County seat has long suffered from a bad reputation.

When visitors do come, many stick close to the historic, green-domed courthouse and other county buildings that anchor the downtown.

“Honestly, we only walk from our cars, that are up at the lot, to here,” said Syndey Perkins, a Villanova University student interning for the clerk of courts this summer. “You can tell relative to other towns that you would feel less safe.”

As other area hubs like West Chester and Media have turned their once-faded downtowns into destinations, Norristown’s large number of rental properties and relatively high crime have so far resisted the revitalization.

Now, at least one of those factors is improving. Violent crime has dropped by a third in the past three years, but a trip around the borough shows that opinions are slow to change.

A push for “community policing”

Local historians have chronicled Norristown’s half-century slide from bustling commercial borough to struggling suburb. No single factor explains the change.

But one connection is clear — as businesses and homeowners emptied out, crime crept up.

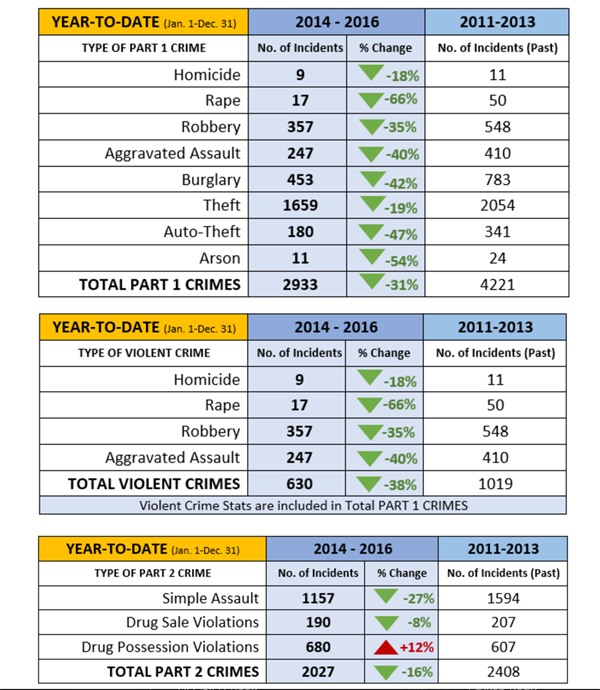

In 2013, there were 1,400 of what are called Part 1 crimes — the really serious ones like murder, rape, assault and burglary, all in a borough of 34,000 people. Three of Montgomery County’s 12 homicides were committed in Norristown that year.

2013 is the same year police chief Mark Talbot took the helm and vowed to reduce violent crime. To do that, he began employing an idea called “community policing.”

That means “doing things to show the public that you care about it,” he said. “You find ways to include the voices of people you work for into your operation.”

Community policing, also sometimes called community-oriented policing, has become a buzzword in recent years — seen as a way to reduce crime and heal tensions that can erupt between police and the communities they patrol.

Norristown is nearly 30 percent Latino and 35 percent black, but the police force is comprised mostly of white males who live outside the borough. And while the tactics of community-policing can sound hokey — “coffee with a cop” and “water ice with a cop” events are part of the department’s charm offensive — it has a serious focus. Cooperation between residents and police can lead to more successful convictions of violent offenders, reducing residents’ chances of being victimized.

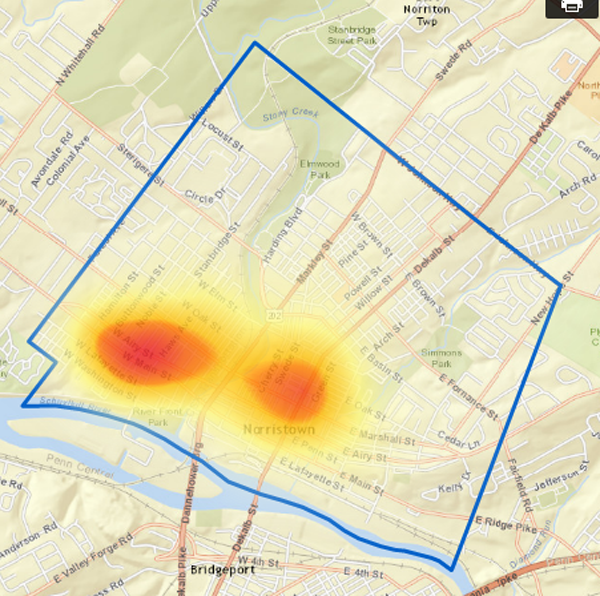

Under Talbot, who is African-American, the department also began using the crime data it collects differently, modeled on a nation-wide push called the Police Data initiative. First, police started making crime statistics public, to help build trust and be more accountable to residents. Second, the department began using data about the locations and types of crimes as a literal map of how to focus their police work, devoting more time and attention to hot spots that are disproportionately dangerous.

“Someone stole my flower pot, someone broke the window on my car. My tire got flattened… They’re all non-priorities,” said Sergeant Ken Lawless. “Because the priority is instead that officer being involved in the plan, the plan for crime reduction.”

New priorities at work

On a recent Tuesday morning, Lawless noses his police vehicle up and down Norristown’s narrow streets, pointing out the places in the southeastern part of the city that his unit watches.

“I like to have officers stop into the McDonald’s a couple of times,” He said. “The other place is Green and Marshall [streets]. We’ve had issues there.”

As the day stretches towards noon, police backburner some nuisance calls to bust a drug dealer officers followed to Markley Street.

After the arrest, Detective Adam Schurr holds out his hand with the spoils: tiny plastic bags of heroin and crack cocaine. Police recovered about $500 dollars worth of heroin and $200 worth of crack cocaine from the right cargo shorts pocket of the suspect, now in custody, according to Schurr.

Det. Adam Schurr holds out heroin and cocaine found in the pants pocket of a man Norristown Police arrested minutes earlier. (Laura Benshoff/WHYY)

Norristown police say these new priorities are working. Since 2013, each year there have been fewer violent crimes than the year before, for a total of 400 fewer violent crimes.

“I think that’s one of the things that’s happened is a significant, and meaningful crime reduction,” said Talbot, noting that some types of crime dropped by more than a third.

Violent crime has trended down nationwide over the past two decades, but there have been small increases in the country’s violent crime rate over the last couple of years. Norristown seems to be bucking that trend, drug possession charges were the only category to increase since 2013.

The community policing approach has also won Talbot some fans. “I think he did a great change by allowing the residents to be more involved and showing his department how to interact with the residents,” said Doris Smith Starks, head of the town watch and a long-time “Norristonian.”

But in recent weeks, a spike in gun violence seems to confirm other residents’ worst fears.

Around 5 p.m., Tony Timmons sits on a low wall in front of the courthouse, waiting to go to work cleaning offices in the county government building across the street.

When asked if Norristown feels safer, he shook his head. “There’s too much shooting going on here.”

Of the five of reported shootings in July, two were fatal. In response to the outbreak, Chief Talbot released a statement, saying the police have assigned extra officers to spend time in the affected areas.

Still, Timmons, who’s lived in Norristown for more than two decades, said he’s skeptical that crime is going down in the borough. All he has to do is look at his neighbor’s stoops.

“Ain’t no sitting on your porch any more,” he said. “Because you don’t know what’s going to happen.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.