Princeton exhibit reminds us that division and hatred are nothing new

As we obsess over the crises of our times, we may lose sight that humans have been warmongers since the very beginning. Differences over religious, philosophical and political thoughts, or even how to raise a family, have always led to bloodshed.

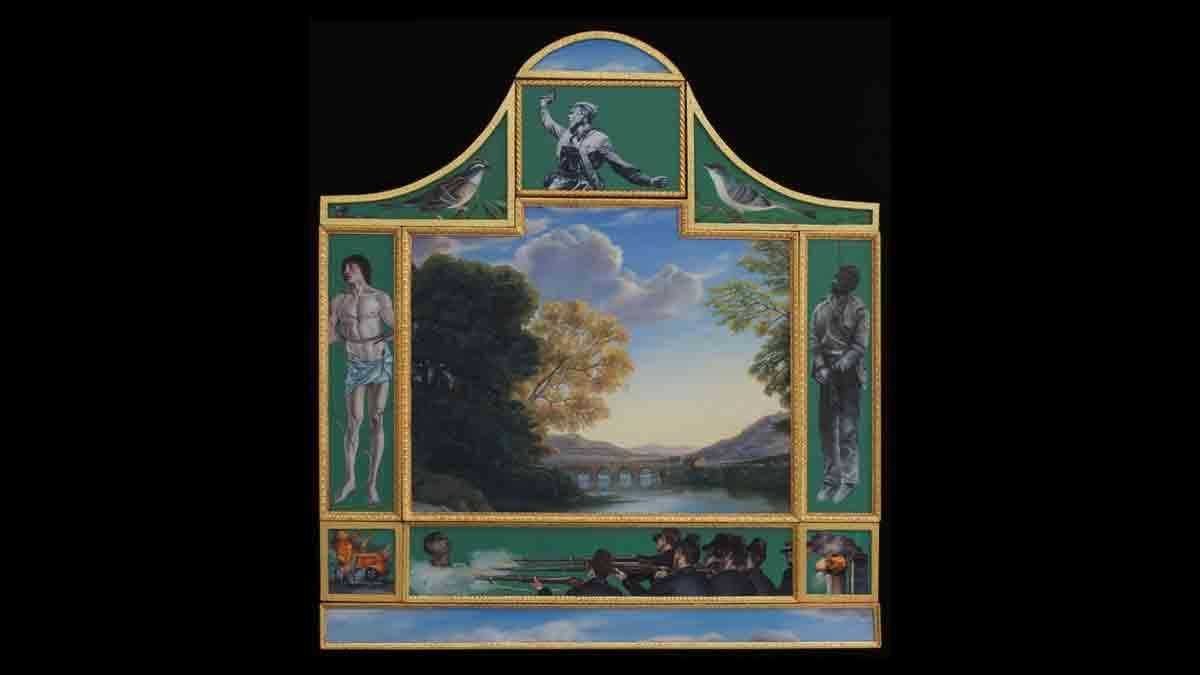

In Gods of War, on view through March 1, 2017, at the Woodrow Wilson School’s Bernstein Gallery in Princeton, artist Phyllis Plattner reminds us how religious iconography depicts the violence humans inflict on each other in the name of religion. Her paintings—oil and gold leaf on assembled panels that resemble Italian Renaissance altarpieces—contrast angels with the pierced and bloody bodies of martyrs, the feet of Christ with a prosthetic leg, the folding façade of the World Trade Center with warriors of earlier times.

Each assemblage is pieced together from smaller paintings framed in ornate gold with references to art history, from illuminated manuscripts to Picasso’s Guernica. Angels float above scenes of war, from China to Greece and beyond. These retablos are brilliantly colored, though individual panels occasionally appear in black and white, like photographs in a newspaper of war-torn cities or fighter planes. War is a grainy, black-and-white affair.

Babies are paired with angels, with Christ’s crown of thorns, the white hoods of the KKK and a mother in a hijab. A man with a bag over his head and a red number tattooed on his chest is next to a shackled man with a gun pointed at his head. In another work, Plattner pairs toy soldiers with armed children.

Children are revered for their innocence, but some are not so privileged. In one, an Elizabethan doll-like figure is surrounded by the Napalm girl—the 9-year-old child fleeing naked from a village in 1972, during the Vietnam War, immortalized in the Pulitzer Prize-winning photograph by Nick Ut—and a young armed soldier, as others flee burning villages.

“The catalyst for the paintings is my horror at the ubiquity and inanity of warfare throughout the history of the world,” said Plattner. “These paintings remind us that all cultures have made art depicting and glorifying their wars. Not until Goya did the depictions of the madness of war appear.”

In 1814 Francisco Goya painted “The Shootings of the Third of May 1808 in Madrid,” a gut-wrenching portrayal of a man with arms upraised before a firing squad, an expression of horror on his face. It was an unprecedented depiction of a man’s last minutes of life.

“Art is made from two big bags of different stuff,” says Plattner, a professor of art at the Maryland Institute College of Art since 1987. “In one bag is everything related to ideas, thoughts, conceptions, notions, emotions—the content. In the other bag is all the stuff that you make it out of.” Unfortunately, the two bags are not always in sync. “When they are it’s totally wonderful.”

She credits her marriage to a cultural anthropologist, with whom she has traveled to developing countries, as having an impact are her life and work. The couple arrived in Chiapas, Mexico, on the day of the Zapatista uprising in 1994—an event that left a profound mark on her work.

Some of the characters in her paintings resemble the dolls made by Zapatistas, carrying AK-47s and wearing ski masks and ammunition belts, an endearing mix of innocence and terror. “Children sell the dolls on the street by the truck full,” said Plattner, who began collecting them.

Plattner also lived in Italy where her husband was doing fieldwork. She brought along her Chiapas dolls and placed them in the windows, painting them in charcoal and pastel. She liked the contrast of the classical lace window curtains and the strange Chiapas dolls, each different forms of folk art. Returning to the U.S., she started painting the dolls in oil, with gold behind them, and glued these to panels, suggestive of a Florentine religious painting.

Plattner found her ideology evolving. “Was I making saints out of warriors? I couldn’t figure it out. All my life I’ve been horrified by war, especially the combination of war and religion. There’s so much violence in religious imagery.”

Altarpieces are supposed to be objects of meditation, concentrating the viewer’s gaze on the Christ or Madonna for reflection and penitence. Plattner began to see similarities in the invasions of Moors, Germans and Gauls, and staged the Zapatista dolls as actors in Renaissance and Baroque Italian masterpieces. Thus we see Zapatista dolls at the Last Supper.

She was adapting the drawing style of Rubens, the brush technique of Goya, to the wars of Mexico. Each retablo tells a story.

The beautifully rendered images of deplorable violence have been described as semi-classical paintings that depict bombings, shootings and decapitations, and are a poignant reminder that we are as barbaric as our ancestors.

The Bernstein Gallery is located in Robertson Hall, Woodrow Wilson School, Princeton University campus. Gallery hours Monday through Friday, 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. and by appointment on weekends: 609-497-2441.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.