Connecting sacred wisdom to Jewish art at Old City gallery

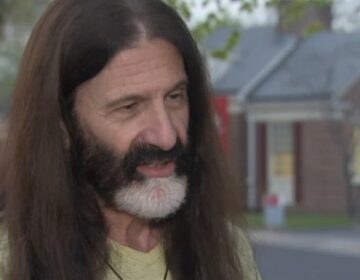

Rabbi Zalman Wircberg (Susan Richardson/for newsWorks)

During the recent Jewish high holy days, I was able to score a few minutes with my friend and neighbor, Rabbi Zalman Wircberg, the co-director of the Old City Jewish Art Center.

“So a priest and a rabbi walk into an art gallery and …”

No, really, we did. During the recent Jewish high holy days, I was able to score a few minutes with my friend and neighbor, Rabbi Zalman Wircberg, co-director of the Old City Jewish Art Center.

It was late in the afternoon on a day of fasting between Rosh Hashanah — the Jewish new year — and Yom Kippur. He didn’t deny the toll of the day’s low blood sugar, but he simply used it as invitation to be more intentionally present to the conversation — which, Wircberg said, was his commitment to the new year ahead. I was touched and impressed.

“All beginnings are difficult,” he said, “so I’m starting the year with a fresh challenge. I want to rise to that practice when it’s hardest.”

That intention of being fully present to people jibes with the intention behind the art gallery. I’d often enjoyed wandering in through their perennially open door for the double-benny of intimate art space and welcoming community. Art and community usually come in pairs, anyway, but the OCJAC weaves in a third dimension, that of the wisdom teachings from Judaism’s rich heritage.

It’s evident in the art, the printed explanatory notes peppered throughout each exhibit, and the open community th gallery welcomes every Friday for Shabbat. It was also delightfully embodied in our conversation, threaded with Wircberg’s heartfelt wisdom and impish wit.

The ‘why’

Co-director of OCJAC with his wife Emunah Wircberg, and Rabbi Menachem Schmidt (who founded the gallery in 2006), the young rabbi came aboard about a year ago, moving from Brooklyn and a job with a simpler focus to Philly and the dizzying network of tasks that an art gallery and its community involves.

As to why he made the switch, Wircberg is characteristically both informative and wise. “First, you have to ask about the ‘why’ of the organization,” he says. “That’s what drives me and gets me up every morning. People often go to a product first and explain it instead of starting with the ‘why,’ the essence of the thing. Only then does the rest make sense.”

The “why” of the gallery is simple, he says: “To nurture people from within. The ‘why’ of Jewish wisdom shown from artists’ insides to viewers’ insides. The gallery can impart help and wisdom to others, but thanks to the medium of art, that happens not by imposing the wisdom but by nurturing it,” Wircberg said.

“On a First Friday, someone can step in, munching on a brownie, and relate to something on a deeper reality,” he explained. “People often look at art as separate from holiness, but by us bringing these messages based on Jewish themes and quotes and the holy days in through the art, it shows how the art is cohesive with the spiritual message.”

Finding sacredness outside of a house of prayer

Wircberg had arrived at this understanding through some pretty interesting experiences — starting as soon as he could walk. “For me growing up in Brooklyn, as a child sort of in a box, something would be holy and sacred and the other stuff would be mundane and unspiritual, and they weren’t connected,” he remembers. “But as I grew up and had the courage to look out of the box, I felt it’s not just in the synagogue or house of prayer where you can find sacredness and holiness.”

At first, Wircberg seemed shy about what he sees as a lack of formal artistic background, but as we talked, his deep connection to art and religion became clear. “I believe that people have some spark, a soul. When God made me and my soul, He took it from the realm of the arts. But it took time to manifest it in something like a gallery. The seed was planted at a young age. It took time to be watered and grow. “

Actually, that seed was first planted in a basement in a yeshiva in Brooklyn. His father is a teacher at Hadar Hatorah Rabbinical Seminary, particularly helping those who didn’t have background in observant Judaism, many of whom were graduate students and artists.

“Friday night, we’d have a Shabbat in the basement. It was an old raggedy place, like something out of the 18th century. I was going there from a young age, maybe 3, as soon as I could walk on Sabbath,” said Wircberg. “At the washing station was a huge beautiful calendar [someone had painted] with all the holy days drawn in a circle on the wall. That just struck me. It was beautiful. It was art, but in a context, and art that taught. You couldn’t separate out the life and the art.”

He remembers the physical joy of the evenings — once, as a toddler, even spilling a bowl of hot chicken soup and still returning undaunted to the dancing, to the amusement of the adults there.

Reconnecting to the simplicity of youth

Fast-forward to his own adulthood, and life, art, and context remained connected. In 2007, Wircberg had come down to Philly for the weekend and joined in the gallery Shabbat. “As I came in, there was only one seat open in front of a beautiful family, of whom I knew the dad. There sat Emunah. As we sat and talked over kiddish and challah, we got to know each other and formed a friendship. So when we dated and got married, something in our guts felt we were destined to come back to continue our mission here: where we met, where we started off.”

So for Wircberg, his religious work has continued in context: “not in a private home, not a synagogue, but in an art gallery, with people from all walks of life and cultures, sitting in harmony, sharing ideas and understanding each other.”

As we finished up our talk and the afternoon shadows grew longer, we returned to the potency of the holy days. “For me as a human,” he said, “these days are about trying to reconnect to my inner self, my essence, who I was when I was younger. To take out a picture of myself when I was a child and look at it and see the simplicity, the courage to be happy.

“Things can get torn through life, we have to work hard and toil to accomplish. But to do it, we need to be rooted in and be reconnected to our selves. This month is a time for me to do that, to reconnect to the child who would dance after spilling chicken soup!”

Which translates pretty well into a sweet new year — L’Shana Tovah. “Reconnecting myself, reconnecting other people. That’s the ‘why’ of the gallery.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.