Pennsylvania Hospital exhibit looks back on Colonial cures

In the 18th century, many familiar plants were exalted as powerful medicine. Sometimes those old-time remedies were on target; other times, not so much.

Pennsylvania Hospital, the nation’s first hospital, now offers an exhibit called “Flower to Pharmacy.”

Colonial doctors believed the ancient idea that well-being depends on a balance of body fluids known as the four humors: phlegm, blood, yellow bile and black bile. They used bloodletting and plant medicines to help patients sweat, purge or flush the body back to good health.

Stacey Peeples, curator of the Pennsylvania Hospital exhibit, says plants were a huge part of colonial medicine.

“You might use the flower of one, the root of another, and bring together concoctions that you would drink, or take as a pill,” Peeples said.

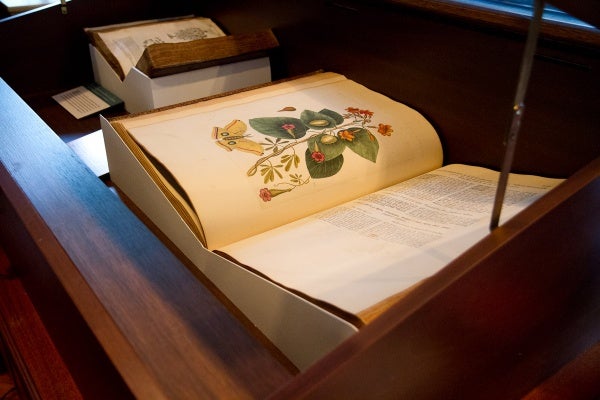

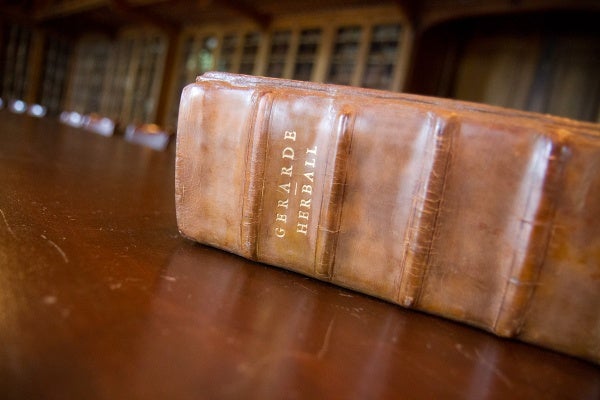

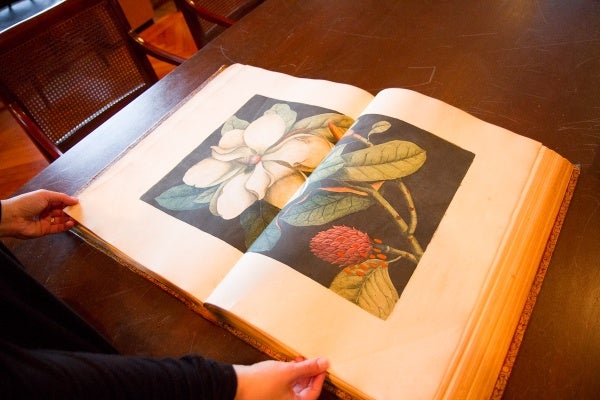

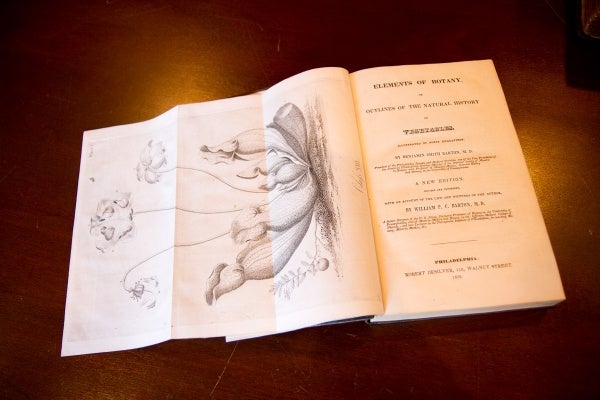

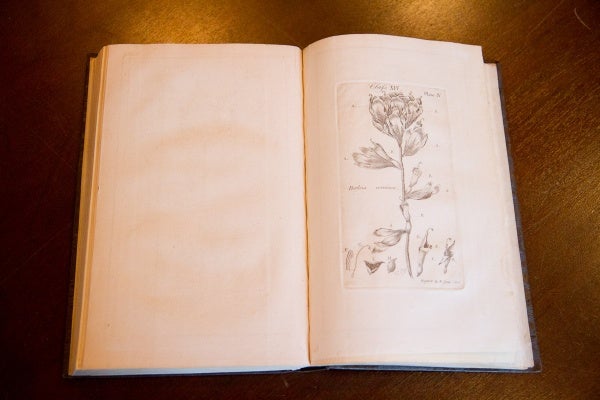

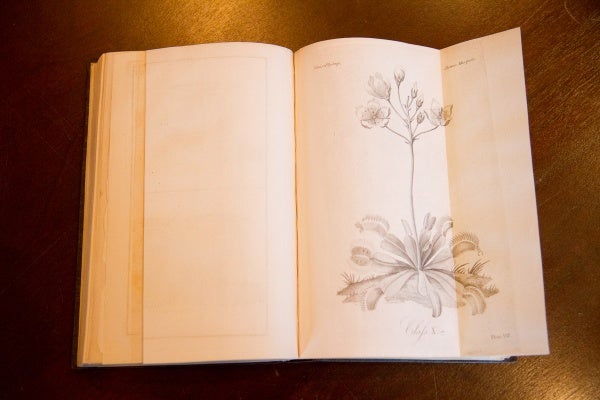

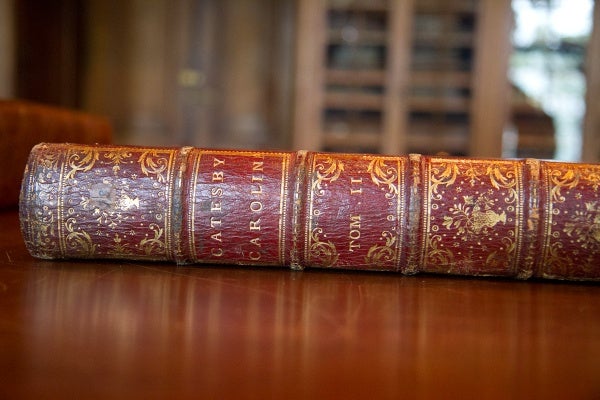

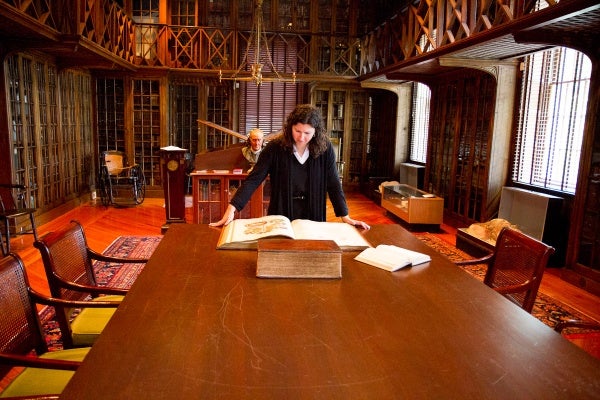

The collection includes elaborately illustrated, and well-preserved, reference books culled from the hospital archives. Doctors would stop by the lending library to look up an herb or double check a symptom before sending a prescription to the apothecary.

Ginger was a fix for flatulence. The weed meadowsweet is recommended for arthritis. You can look up a way to soothe hemorrhoids and find a long lists of cures for a woman suffering a fit of hysterics.

In “The American Practice of Medicine,” physician Wooster Beach describes both exotic plants and everyday kitchen herbs such as peppermint: “The odor of this plant is agreeable and penetrating, slightly bitter, followed by a sensation of cold in the mouth.”

The exhibit includes physician journals and handwritten lectures notes from medical students in Philadelphia in the mid-1700s. Peeples says it’s fun to try and decipher their scrawl.

“It would be very much like how you take your notes in class today,” Peeples said. “You know what you wrote, but nobody else had to be able to read it.”

Besides plants, the volumes enumerate the many healing properties of mercury, arsenic and other minerals that would be considered toxic today.

“We like to call it heroic medicine, that idea that the physician will go to any means to cure you, even if meant killing you,” Peeples said.

The authors and physicians also included some warnings.

“For them to say something will kill you immediately probably means it was pretty harsh given the amount of enemas and purgatives these people were taking,” Peeples said. “It had to be really bad.”

Sometimes a “cure” did more harm than good, but herbalist Wendy Grube says, often, colonial doctors got it right.

“Why did these traditions happen? They happened because they were effective. I don’t think people really waste their time on things that aren’t effective,” she said.

Grube uses botanical remedies in her work as a nurse practitioner, and teaches a class on alternatives therapies at the University of Pennsylvania. Many modern clinicians study plants, she says, to help guide people who already use herbal remedies, and to offer patients alternatives with fewer side effects.

If someone is in a car accident, Grube says, definitely take them to the emergency room but many cough-and-cold ailments lend themselves well to herbal products.

Eighteenth century doctors didn’t know about bacteria or if a plant could stop a virus, but careful observation lead them to legitimate remedies.

“When you think about sage, what do you think about? … Thanksgiving. Sage is an antimicrobial; it really might kill some of that bacteria that’s sitting in that stuffing,” Grube said.

“Flower to Pharmacy” documents similar observations as well as wisdom passed down from native healers and naturalists.

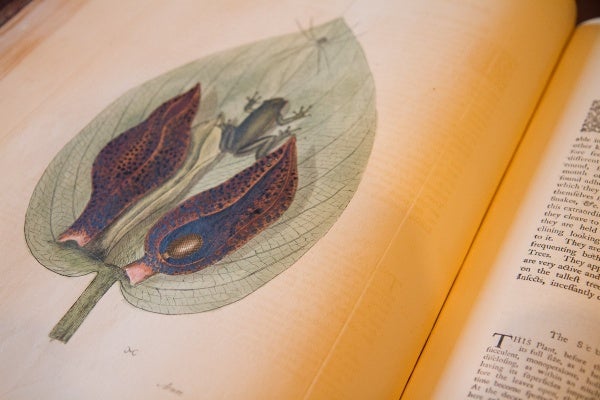

One of the most colorful volumes in the exhibit– Mark Catesby’s “Natural History of Carolina” — is like a picture book of insects, animals and native plants.

Curator Stacey Peeples says physicians studied those pictures closely looking for hints to a plant’s medicinal power. If something was shaped like a kidney, she says doctors thought: ‘It just might be good for your kidneys.’

“You can kind of understand where they were going with that, without having the tools that we do today, that was a pretty good way to start thinking about things,” Peeples said.

Pennsylvania Hospital’s Flower to Pharmacy exhibit can be viewed at Pennsylvania Hospital. The exhibit is open to the public from 9am-4:30pm, Monday-Friday through June 1, 2012.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.