Closing arguments set in shorter than expected Fattah trial

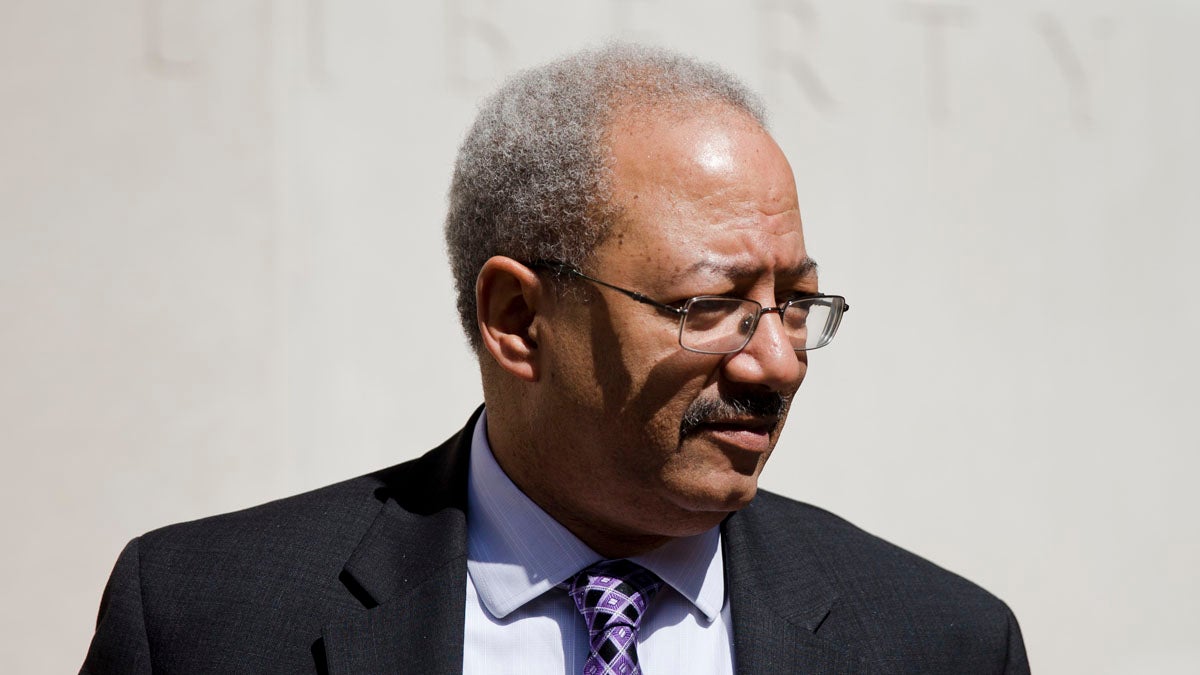

Closing arguments in the federal corruption trial of U.S. Rep. Chaka Fattah begin Monday (AP file photo)

The fate of indicted U.S. Rep. Chaka Fattah will soon be in the hands of a Philadelphia jury, and far more quickly than initially projected.

After four weeks of wide-ranging and, at times, dizzying testimony, closing statements are scheduled to begin Monday. Prosecutors and defense lawyers initially said the case could last up to two months.

The government’s case took up most of the trial.

Prosecutors presented jurors with scads of email chains, campaign finance documents, grant applications and bank statements. They also heard from dozens of witnesses — seemingly anyone with ties to the illegal activities alleged in the government’s 28-count indictment.

FBI agents, accountants, former congressional staffers, grant officers, even Pennsylvania U.S. Sen. Robert Casey and former Pennsylvania Gov. Ed Rendell.

A big piece of the government’s case rests on the testimony of two savvy political consultants who worked on Fattah’s failed bid Philadelphia mayor in 2007: Thomas Lindenfield and Gregory Naylor.

Both pleaded guilty before trial.

On the stand, the operatives spoke plainly about conversations they had with the congressman about an illegal $1 million campaign loan, which sits at the heart of the case.

Fattah not only took the loan, prosecutors said, but also orchestrated the theft of federal and charitable donations to help repay part of it — the $600,000 the campaign did use.

The money allegedly snaked its way back to a wealthy lender with the help of a nonprofit and for-profit organization with ties to Fattah and a series of sham documents.

No paper trail, defense argues

Fattah’s lawyers maintain that their client had “nothing to do” with the loan or its repayment. Instead, they said, Lindenfeld and Naylor pulled all the strings.

Their proof: Fattah’s name or signature cannot be found on any documents tied to the loan.

“As far as Congressman Fattah knew, all money coming into the campaign was lawful,” Fattah attorney Mark Lee told jurors during his opening statement.

While testifying, Lindenfeld acknowledged nothing was put in writing. Prosecutors say that was done purposely so Fattah could remain removed from the crimes.

“We spoke verbally. We didn’t speak that way,” Lindenfeld told jurors.

Fattah is also accused of using campaign cash to help pay off some of his son’s college loan; encouraging Lindenfeld to create a sham environmental nonprofit to settle up campaign debt; and being bribed by a wealthy friend who wanted to be a U.S. ambassador.

Prosecutors say Herbert Vederman, a former deputy mayor, “showered” Fattah with money and gifts in exchange for his efforts trying to secure the post, including $18,000 for a home in the Poconos. Fattah and his wife, former NBC10 anchor Renee Chenault-Fattah, then allegedly concocted a sham car sale to cover their tracks.

Fattah sent letters extoling Vederman’s resume to Casey and members of the Obama administration, but Vederman didn’t get the position.

Casey said Fattah didn’t cross any lines. Rendell, who is close friends with Vederman, insisted nothing illegal happened and that the government was “overreaching.”

“Federal prosecutors don’t understand the political process. They’re very cynical. They assume everyone does everything for ulterior motives,” said Rendell. “No one could do something because they’re your friend.”

The co-defendants

Vederman is one of four associates charged alongside Fattah. Also charged under the indictment are Bonnie Bowser, a former chief of staff at Fattah’s congressional office in Philadelphia; Karen Nicholas, a former congressional staffer and CEO of the Educational Advancement Alliance, a non-profit Fattah founded; and Robert Brand, founder of the for-profit organization Solutions for Progress.

Nicholas is accused of obtaining a $50,000 federal grant for an already-held education conference, then using the cash on herself.

During opening statements, their lawyers also maintained that Lindenfeld and Naylor were at fault and that the government had “cherry-picked” and “taken out of context” documents and facts in order to build a narrative they felt could best win convictions.

Neither Fattah nor any of his co-defendants testified at trial.

Fattah is charged with racketeering, bribery, bank fraud, wire fraud and other offenses.

Even if Fattah is acquitted, he won’t be returning to Congress in 2017. After more than two decades in office, he lost April’s Democratic primary to state Rep. Dwight Evans.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.