‘Clean pajamas are not enough’: Critiques of New Jersey jails mount amid pandemic

Incarcerated individuals and their loved ones continue to report woefully inadequate conditions in New Jersey jails.

Husband and wife Darnell Williams and Patrice Mosley in front of their Millville home; Williams was recently released from the Cumberland County jail. (April Saul for WHYY)

Ask us about COVID-19: What questions do you have about the current surge?

It’s not known when a prisoner first navigated a crawl space at the Cumberland County jail, broke through a brick wall, and used a rope and pulley system to smuggle in contraband from the Bridgeton, N.J. facility’s rooftop with the help of friends below.

But during the chaos of the coronavirus pandemic, the venture got plenty of use.

“A little tunnel was created, kind of like the TV show ‘Hogan’s Heroes,’ where the inmates were able to move certain bricks in an area of the jail that allowed drugs, alcohol, and God knows, perhaps weapons [to come in,]” said attorney Stuart Alterman, who represents the correctional officers’ union, PBA Local 231.

When correction officers shut down the enterprise in December, prisoners told a guard that declined to be identified that they’d been using it for months.

“The officers found marijuana and bottles of booze and probably ruined a nice Christmas party for the inmates,” Alterman said.

Cumberland County spokesperson Jody Hirata said the matter was an ongoing investigation, but that contraband had been seized and the individuals implicated have or would face appropriate charges.

The revelation might be the least of the jail’s worries, as many prisoners and staffers decry the facility’s response to the deadly pandemic as woefully inadequate. The jail has been a COVID-19 hotspot: with less than 300 people incarcerated there, Alterman estimates that roughly 65 prisoners and 19 staffers have already contracted the coronavirus; Hirata cited slightly different numbers, saying that 52 prisoners and 21 staffers had tested positive.

When COVID-19 broke out among the jail’s kitchen workers, the prisoners “ate pizza from the outside and little TV dinners,” said Patrice Mosley, whose husband, Darnell Williams, was recently released. The guard said the menu included cold cereal and hard-boiled eggs and has continued for two months. Hirata said “improvised meals” were served for two weeks after a COVID-19 incident that impacted food service, and that the “epidemic” periodically causes the jail to serve meals from “take-out establishments.”

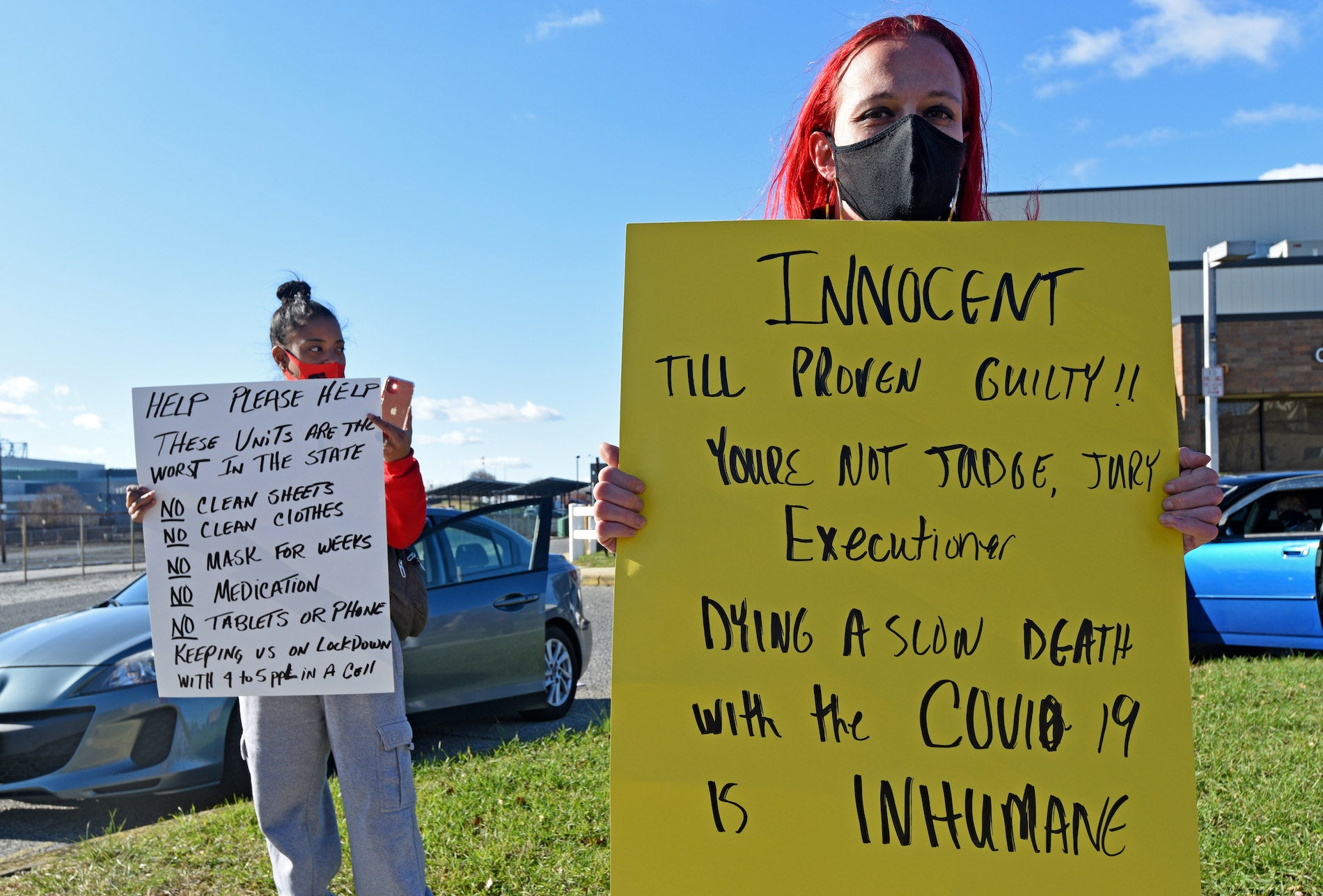

Kimberly Piraino was told by her boyfriend, who is incarcerated in the Cumberland County jail, that prisoners haven’t been given face masks in three weeks, have not been outside since September, and have been prevented from seeing lawyers, attending court appearances, and even going to the jail library as coronavirus has spread throughout the facility.

Some of the mail Piraino has sent to the jail in the last month has been marked “unable to be delivered” and returned to her. The guard said that the mail problem was not deliberate, but a result of short-staffing, although Hirata said the DOC knew of no such issue.

“They keep them like caged animals,” Piraino said.

Fifty miles away, at the Camden County jail, things appear to have changed since WHYY first reported on the facility’s pandemic response earlier this month.

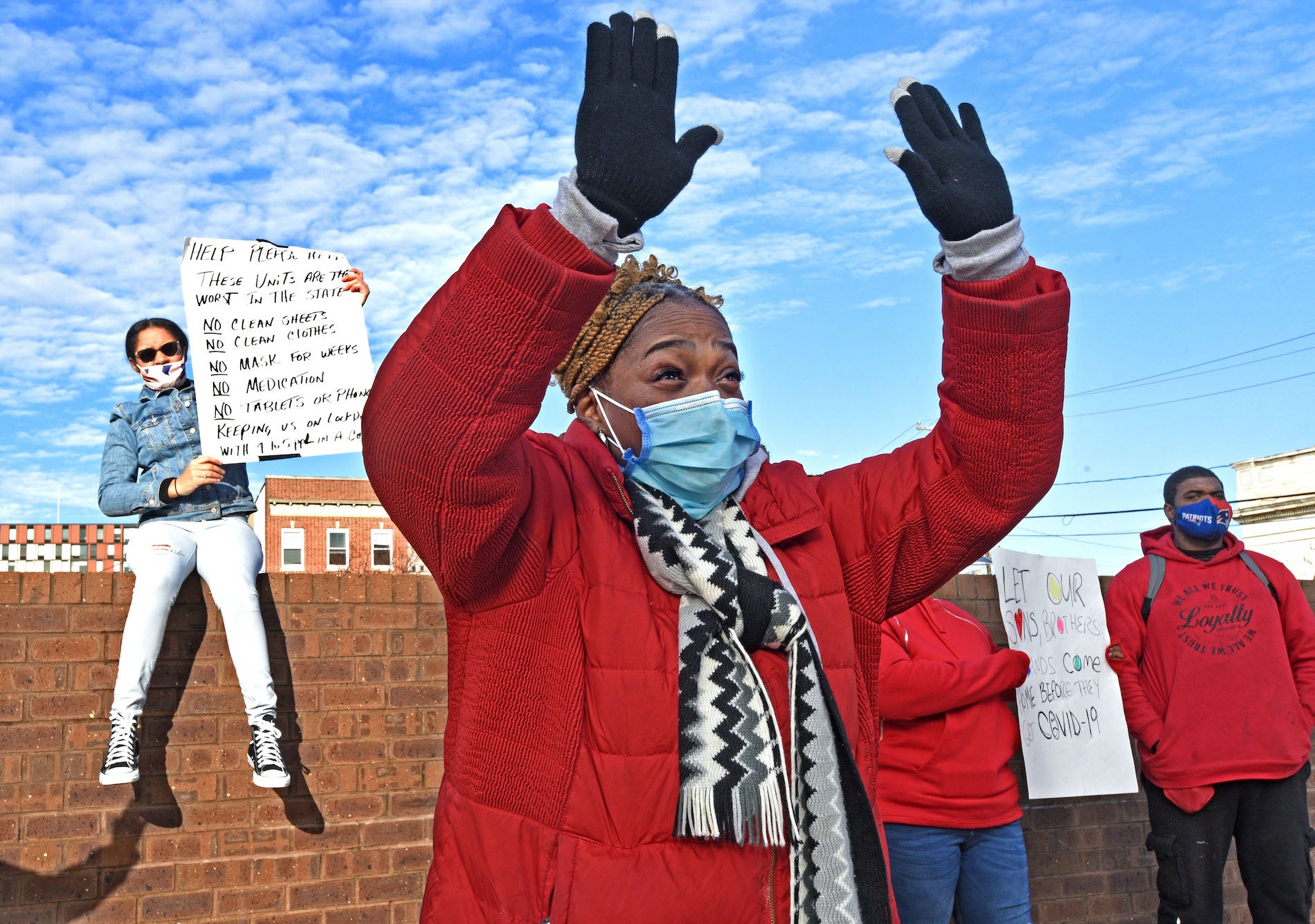

For weeks, Dana Butler had been worried about her son, David Wilmer, a prisoner with a heart defect who’d contracted COVID-19 in November. She was frustrated when a judge denied Wilmer a chance to be seen by his cardiologist and horrified when jail medical staffers tried to get Wilmer to take medications that were contraindicated because of his condition. She’d even taken to the street to protest what she believed to be the jail’s mishandling of the pandemic, carrying a sign that read, “David Wilmer, We Love You.”

At the beginning of December, Camden County spokesperson Dan Keashen reported that 114 prisoners and staffers at the Camden County jail had tested positive for COVID-19. At the time, people inside the jail were reporting a lack of masks and testing, being subjected to extensive lockdowns, and complained that prisoners who had coronavirus were put in close proximity to those who did not.

Then, during a Dec. 21 call to her son, Wilmer said that the prisoners on his floor “were just told that if they didn’t wear a mask, their charges would be upped” and they’d be transferred to a floor with people incarcerated for violent crimes.

“How the hell are you going to up somebody’s charges and send them up to be with the murderers and rapists for not wearing masks?” Butler asked.

According to Keashen, “internal disciplinary action in front of a review board” would be used if a prisoner endangered others by refusing to wear a mask; actually moving a resident’s unit, said Keashen, would be “egregious.”

Prisoners also reported receiving a memo this week telling them to stay six feet apart. The memo also described COVID-19 symptoms, which Wilmer — who said he’s still experiencing after-effects of the virus — found amusing, Butler said.

“He told me,” said Butler, “‘Hell, I still have at least six of those symptoms!“

Wilmer’s account echoes that of other prisoners, who said — with a few exceptions — that since several protests earlier this month, they have received new blankets, masks, and clean linens. They report that the walls of the facility are now dotted with posters announcing mandatory mask-wearing whenever prisoners leave their cells.

Last month, LaToya Fields’ incarcerated partner, Todd Oliver, had a heart attack and contracted COVID-19. Oliver was said to be surprised by the stern warnings about masks.

“I told him, don’t be nervous,” Fields said. “Be glad they’re doing what they’re supposed to be doing!”

Unlike the Camden County jail, where conditions seem to have improved somewhat, Cumberland County prisoners and their loved ones said that jail has yet to make any adjustments.

Piraino said that her boyfriend told her that prisoners were reportedly living 24 to a unit, with two toilets, one sink, and one shower, and that beds were placed two-and-a-half feet apart. The guard, who was interviewed at the end of a 17-hour shift at that jail, reported that on a recent night only five corrections officers patrolled the facility.

“We haven’t seen the wardens in months,” he said. “It’s a sad place now.”

Alterman described the outbreak in the jail as “a 10-alarm fire that’s burning out of control” and linked it to inadequate staffing.

“The guards probably didn’t notice the tunnel,” he said, “because there were so few of them.”

Hirata said staffing challenges predated the pandemic and attributed them to “chronic delays in receiving qualified candidates from NJ Civil Service, unanticipated use of PTO, FMLA, and other forms of leave.” She also said that as some of their detainees have been moved to other facilities, guards have moved to open positions in those jails.

Alexander Shalom, a lawyer with the American Civil Liberties Union of New Jersey, said the COVID-19 crisis in the state’s jails comes down to simple math.

“It’s not that we’re arresting more people than usual but in the absence of any mechanism for getting people out, the numbers are going up and up,” Shalom said.

Hope for thinning incarcerated populations is on the horizon with a motion for an order to show cause filed this month in the state Supreme Court by ACLU-NJ and New Jersey’s Office of the Public Defender. The motion would ask the state to explain why anyone who’s held pretrial for six months or more on second, third, and fourth-degree charges shouldn’t be released with conditions; and that judges should also consider for release those with first degree offenses with no presumption of detention; homicide, certain sex offenses, and a few others are excluded. A decision is expected in January.

“There’s a lot of people in there that certainly don’t need to be there,” said Jennifer Sellitti, director of training and communication for the Office of the Public Defender.

Shalom is calling for “a reexamination of our obsession with incarceration” to ameliorate the crisis.

“You cannot provide social distancing in jails,” Shalom said. “The only way you can do it is by getting people out.”

He called the 52 prisoners who have died of COVID-19 in New Jersey an “astonishingly high” number.

“Let’s be clear here that if people get sick in our prisons, it puts all New Jerseyans at risk,” Shalom said. “Someone gets sick in prison and winds up on a ventilator, that’s a ventilator that your grandma no longer has access to.”

Connie Kellum is happy for the new masks and fresh linens at the Camden County jail but it bothers her that her husband, Alfred Gilbert, a prisoner there, has not been tested for COVID-19.

“We are supposed to hold these people alive, not kill them before the court date,“ she said. “Clean pajamas are not enough.”

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.

![CoronavirusPandemic_1024x512[1]](https://whyy.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/CoronavirusPandemic_1024x5121-300x150.jpg)