Not in the municipal budget? Try crowdfunding

ListenYou’ve likely heard about crowdfunding on web platforms like Kickstarter. It’s where people submit an idea and anyone can sign up to help fund it.

But crowdfunding isn’t just a tool for raising money to produce a movie, manufacture a gadget, or make gourmet potato salad. Communities are turning to this funding model for civic projects.

In 2012, Philadelphia launched what’s believed to be the first city-sponsored civic crowdfunding project in the country, through a platform called Citizinvestor. The Mayor’s Office of New Urban Mechanics headed up the campaign. Story Bellows, a co-director of the office, said the office’s mission is to find innovative ways to meet civic challenges—and funding is always a challenge.

That first project (a tree planting initiative) wasn’t successful, but the office tried again, this time partnering with the Department of Parks and Recreation to successfully fund the Rivera Recreation Center Community Garden. The project was completed this year. Bellows said crowdfunding is definitely a tool the city is eager to use again.

And others are following suit.

Outside tax dollars

State College wants to give it a shot. Earlier this summer, the borough asked residents to vote on a project they’d want to crowdfund. The majority of votes went to park improvements, beating out a mobile app for bicyclists and a public art installation.

Meagan Tuttle, a planner for the borough of State College, said there’s always a demand for more public services so the borough has to find new ways to secure funding in the future.

“The whole idea of crowdfunding is it generates money outside your tax dollars,” she said.

Tuttle said the vast majority of community feedback has been positive, but she’s also heard from a few who don’t like the idea of giving the borough money when they already pay taxes. But she said that’s okay.

“You only give money to it if it’s something you care about,” said Tuttle.

And she said it’s important for residents to know crowdfunding would only be used for small quality-of-life amenities, not as a replacement for tax dollars funding essential services.

Not an end-all, be-all

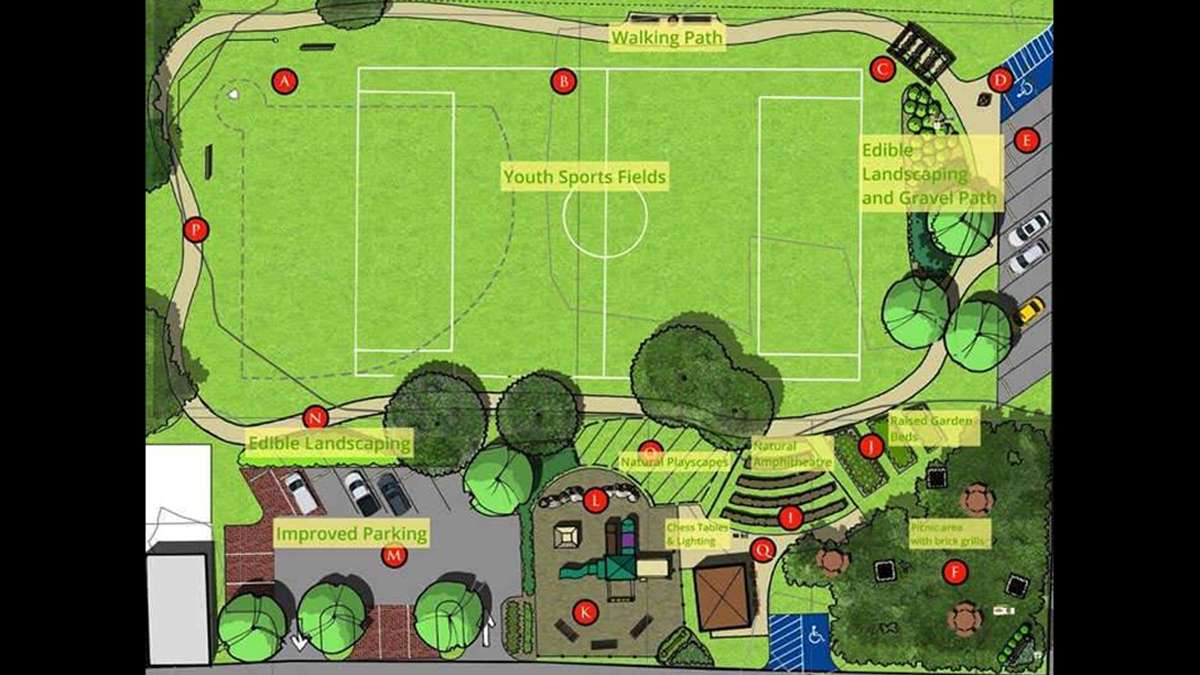

In Carlisle, near Harrisburg, the Carlisle West Side Neighbors group is working with a local non-profit and the municipal government to renovate Heberlig Palmer Park, a community space in a mixed-income neighborhood.

They launched a crowdfunding campaign earlier this year. They didn’t hit their goal, but the web platform they used, Neighbor.ly, doesn’t require a campaign to be fully funded to release the amount pledged. So they got to keep what they did raise. They still need more money–they’ve applied for a matching grant from the Department of Conservation and Natural Resources.

Brenda Landis, who’s led the project, said crowdfunding can allow residents to take the reins of a project instead of waiting around.

She said, “a lot of times you see residents go to a meeting—they’re sort of handing off their ideas and all they can do is keep harping on them.”

But “it’s not an ‘if you built it, they will come,'” she said.

Landis suggested crowdfunding might better be seen as a later step in a process that includes a lot of hard work, creative marketing, and community mobilization.

Surprisingly successful

Rodrigo Davies founded the Civic Crowdfunding Research Project at MIT. His research paper, published last month, analyzes more than a thousand civic crowdfunding campaigns from when the idea was new in 2010 to March of this year.

The campaigns, which raised almost $11 million, ran the gamut from subsidies to a farmer’s market in Massachusetts to a city wifi project in Mansfield, England.

One surprising finding? The success rate.

Davies said he expected it to be lower, since civic projects are a newer thing; “perhaps less sexy than a video game or a technology gadget.”

But on Kickstarter, Davies found projects tagged “civic” had a success rate of about 80 percent, almost double the average on the platform.

According to Davies, the success rate could be because passionate people from the community are often behind the projects. And civic crowdfunding can be really compelling.

“It’s not just asking someone for $10 or $20, it’s saying that in giving that money, they’re also part of a movement that is trying to improve the quality of life of everybody in the area,” said Davies.

He added that it’s important to get the scale right—you have to think realistically about the target financial goal. And it’s key that the “parameters of the project are clear and transparent and the group that’s running the project—whether it’s a volunteer organization, an NGO, or the local government—is credible and trustworthy,” said Davies.

Davies said he doesn’t know if crowdfunding will ever be part of every city’s toolkit, but he doesn’t see it slowing down anytime soon.

“If anything we’re going to see an explosion of platforms before things calm down a bit in 3 or 4 years,” said Davies.

Keystone Crossroads is a new statewide public media initiative, reporting on the challenges facing Pennsylvania’s cities.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.