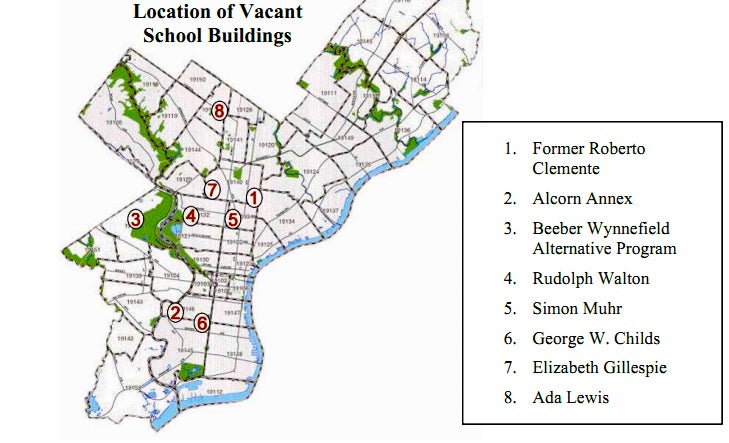

City Controller calls for action on vacant school buildings owned by the Philadelphia School District.

City Controller Alan Butkovitz today accused the School District of Philadelphia of letting eight shuttered district buildings deteriorate into dangerously unsafe condition, and called the empty facilities “catastrophes waiting to happen.”

Each of the buildings – which includes schools closed as long ago as 1998 and 2001 – were examined by investigators from the controller’s office and a licensed civil engineer.

What they found, documented in photos and video, were broken windows, unsealed buildings, empty hypodermic needles and used condoms, human waste, garbage, empty liquor bottles, ominously large cracks in outer walls and other evidence of neglect.

Conditions are so bad at the former Roberto Clemente Middle School (at 5th and Rising Sun Avenue) that the building should be demolished immediately, Butkovitz said. Indeed, the report contends that each of the buildings should be torn down, partly for safety’s sake, partly to make the sites more appealing to would-be developers, a job that would cost as estimated $5 million.

Butkovitz did not share his findings with the school district before releasing them this morning to the press, and the district did not immediately return a request for comment.

But in the past, district officials have said the eight surplus properties cited in the controller’s report would be some of the first to be disposed of using the district’s newly drafted adaptive reuse policy. That policy calls for creating evaluation teams comprised of district, community and politically appointed members to consider new uses proposed by non-profit and for-profit developers for shuttered school buildings.

The same policy is intended to speed the sale of future shuttered schools, including the nine closures recommended by district staff last month.

It isn’t entirely clear how much private-sector interest there will be for some of these sites, particularly those with aging facilities in low-income neighborhoods. Others, such as the enormous West Philadelphia High building (which was vacated only this year, and thus was not included on the surplus property list examined by the controller’s office) seem certain to attract intense developer interest.

The School District of Philadelphia is hardly the only public landowner that has failed to be an exemplary manager of its unused properties. The City of Philadelphia, the Philadelphia Housing Authority, the Redevelopment Authority and other public agencies all own lots and buildings that are neighborhood eyesores and worse.

Butkotvitz, though, contended that the district’s failings as a landlord were magnified by the sheer size of the abandoned school sites. And he said neighbors of the facilities were distressed that these former community assets were in some cases becoming magnets for crime and drug use.

As controller, Butkovitz is the city’s official auditor, but he does not have formal power to audit the state-run school district.

That has not stopped the controller from being a frequent critic of the district, dating back to at least 2005. That was the year Harvey Rice – now Butkovitz’s deputy – left the school district to join the controller’s office, touching off a feud between the two offices that has shown little signs of abating ever since.

In one of many Butkovitz broadsides against the district, he warned in 2008 that the abandoned Thomas Edison High building at 7th and Lehigh posed a risk to public safety. That critique proved prescient. The building was destroyed in a three-alarm fire in August, just weeks after the district had sold the property off to a developer.

Contact Patrick Kerkstra at pkerksra@planphilly.com or Twitter.com/pkerkstra

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.