Catto mural tells of collective resistance in 19th century Philly

A new mural of 19th century Philadelphia activist Octavius Catto shows a collective movement for civil rights.

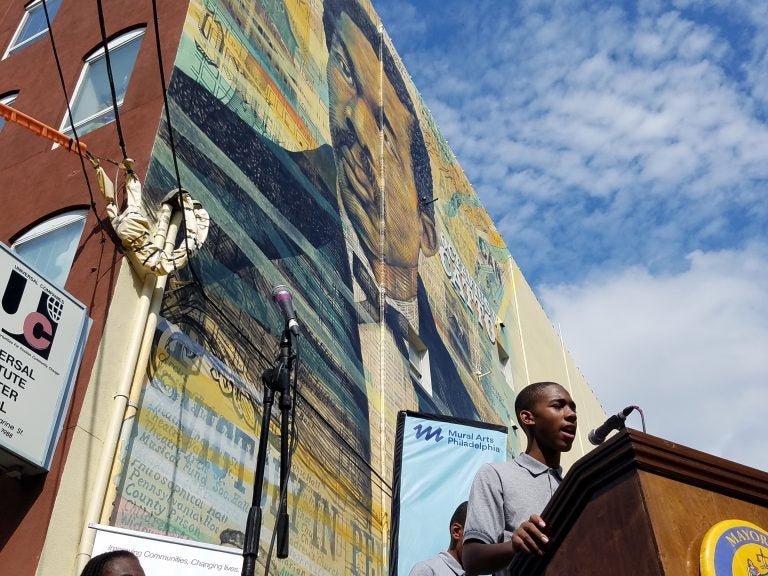

The Octavius Catto mural at Broad and Catharine streets was dedicated at a Tuesday ceremony.(Peter Crimmins/WHYY)

A year ago, a major statue of Octavius V. Catto was erected outside Philadelphia City Hall. Now, a mural of Catto has been completed at an elementary school in the Graduate Hospital neighborhood.

The city school district, which has incorporated Catto in its curriculum, estimates about 11,000 students have now learned about the 19th-century civil rights activist, who was killed at age 32 in the street while trying to rally voters on Election Day in 1871.

“He was a great man,” said Alassane Karamoko, an eighth-grader at Universal Institute Charter School in Philadelphia. “He did many things in that past that a lot of people don’t know about.”

“A forgotten hero, definitely,” concurred classmate Franklin Robinson.

The two boys and many other students crowded in front of the mural they helped paint at Universal charter during a Tuesday ceremony to dedicate the new work on Catharine Street, near Broad. The mural — 120 feet long and 65 feet high — is painted inside a tight breezeway between buildings.

While the giant portrait of Catto is easily visible from Catharine Street, the farther reaches of the image – 120 feet away through a chain link fence – will be lost to the casual passer-by. Some of the details will be primarily for the benefit of the 650 elementary school children going in and out of the school.

“He created the first African-American baseball league,” said Jaylin Collins, another eighth-grader.

“He did everything for civil rights,” said Robinson.

“He was a brave man,” added Collins.

At some point, the details of history get fuzzy: What, exactly, made him so brave?

“I don’t know much,” admitted Karamoko. “All I know really is that he did a lot of good stuff in the past.”

The mural, designed by artists Willis Nomo Humphrey and Keir Johnston, may not answer the “why” and “how” questions. (That information can be found in the 2010 biography “Tasting Freedom.”) The image does a good job with the “when” — the image is overlaid with 19th century newspaper headlines, such as “Fail Now and Our Race is Doomed!” — and the “where” — the image is structured against a map of old South Philadelphia streets where Catto lived and died.

Most prominent is the “who.”

The mural is adorned with smaller portraits of Catto’s contemporaries. Together they initiated a civil rights movement with a trolley car strike and a push to get out the vote. This was nearly a century before Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King Jr.

They included Charlotte Forten, an fervent abolitionist and daughter of sailmaker James Forten, one of the richest black men in Philadelphia. Daniel Payne, a bishop in the AME church in Philadelphia, later became the founding president of the first black-owned American college, Wilberforce University in Ohio.

Fanny Jackson Coppin was an AME missionary who urged higher education for women. Jacob C. White, who played baseball with Catto, was an educator who became Philadelphia’s first black principal.

These people, with Catto, lit a civil rights fire in Philadelphia. Unfortunately Catto was the martyr of the group, shot in the street on Election Day while encouraging black men to vote.

Mayor Jim Kenney, who has long called for recognizing and honoring Catto, spoke at the mural dedication.

“I want all the children here to understand, that man on the wall, and all the people on that wall look just like you. You’re just like them. You can do great things,” he told the group of predominately black youngsters assembled in front of him.

“It wasn’t just the white men in this country that made this country great. It was people of color, women, and other people who made this country great, too,” he said. “They just never got the credit for it.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.