Can we trust the Philly cigarette tax revenue projections? A look inside the numbers

City officials have been pressing hard for a $2 dollar per pack tax on cigarettes sold within city limits. All the proceeds would go to the cash-strapped city schools.

If passed, the city expects the tax to generate $83 million in a first full year of collections, which would go a long way to filling a budget gap that threatens to cause mass layoffs.

You can hear them calling in the street.

They lean on corners, squat on milkcrates, rest on folding chairs – angling for a buck.

At the bustling intersection where Erie and Germantown Avenues slice through North Broad street, they occupy every corner, calling to passersby:

“Loosie! Loosie!”

They’re the city’s black market cigarette hawks.

From packs semi-hidden in coat pockets or under thighs, the hawks market individual “loosie” cigarettes. On a recent hot July Friday afternoon, the going rate on North Broad was 50 cents a pop.

One seller who declined to be named – resting wearily against the storefront of a bodega –offered a bleak portrait of his business.

“It’s real bad,” he said. “You don’t make that much money.”

At this point, this seller and others mostly peddle to smokers who don’t have the cash on hand for a whole pack, or teens who can’t buy legally.

Soon though, the entire dynamic could change.

City officials have been pressing hard for a $2 dollar per pack tax on cigarettes sold within city limits. All the proceeds would go to the cash-strapped city schools.

Philadelphia needs the state’s permission to levy this tax. In Harrisburg this summer, the cigarette tax approval – tucked into a larger piece of legislation – has ping-ponged back and forth between the House and the Senate.

If passed, the city expects the tax to generate $83 million in a first full year of collections, which would go a long way to filling a budget gap that threatens to cause mass layoffs.

Superintendent William Hite has said that if the tax isn’t passed by this Friday, the district will have to decide between two drastic courses of action: either lay off 1,300 employees and see class sizes balloon to as many as 41 kids per teacher, or save money by truncating the school year.

House Majority Leader Mike Turzai (R., Allegheny) visited Hite this week to reassure the superintendent that he intends to get the tax passed sometime this fall.

Many detractors of the cigarette tax plan say that if the tax passes, the city’s revenue projections will not bear fruit.

For one, they say, as cigarette prices grow, black markets at places like Broad and Erie will grow exponentially, undercutting the city’s collection rate.

For that to happen, Philadelphia’s black market would need to grow much more sophisticated in its retail infrastructure.

At Broad and Erie, the sellers I spoke with, most of whom didn’t own cars, said they bought packs of cigarettes from corner stores and delis in the neighborhood, paying the existing $2.61 in state and federal cigarette taxes.

They were aware that tax within the city could jump by $2 dollars, but offered little indication of how the increase could affect business.

“I can’t say,” said the seller. “Nobody knows whether it’s going up or coming down.”

Detractors also say more smokers will elude the new tax by crossing county lines to buy their smokes.

The city view

The $2 per pack cigarette tax, which has the full support of Mayor Michael Nutter, was passed unanimously passed by City Council in spring 2013.

In order to understand why the city is promoting the tax as a reliable source of funding for the school district, it’s important to understand how it compiles its revenue projections.

Given that the city doesn’t now tax cigarettes, it doesn’t have a revenue history on which to base projections.

So it has built them around the results of a regional health survey of 4,000 adults conducted by the non-profit Public Health Management Corporation.

The survey has been done every other year for the past 25 years, the last time in 2013. According to city officials it “meets the highest standards of survey research.”

Based on the the survey, the City Department of Public Health estimates that there are 275,000 adults who smoke regularly in the city. (Of 1.1 million Philadelphia adults, this is 23 percent).

The survey also asks smokers how many cigarettes they burn through each day.

Based on responses to this question, the city estimates that the average Philadelphia smoker buys 237 packs per year.

The city’s logic then goes like this: 275,000 smokers multiplied by 237 packs per year equals 65 million packs per year sold in the city.

If the $2 per pack tax was applied to this 65 million, it would generate $130 million.

But the city understands that the tax hike will cause some Philadelphians to quit or reduce smoking and push others to evade the tax.

After analyzing the effects of cigarette tax hikes in other cities and states, Philadelphia assumes that smoking rates will decline by 5 percent per year over the first three years of the tax.

“There is over half a century of research showing that when you increase prices of cigarettes you decrease rates of use,” said Giridhar Mallya, who led the city’s analysis.

As director of policy and planning for the Philadelphia Department of Public Health, Mallya has campaigned for a city cigarette tax for years, for reasons of public health wholly separate from the issue of school funding.

“For adults, a 10 percent price increase leads to a 3 percent decrease in smoking. So here we are seeing a 33% increase in price from a $2 dollar per pack tax. That leads to about a 10 to 15 percent reduction among adults.”

In addition to this decline, the city also assumes a 30 percent tax avoidance rate, i.e. black markets and buying outside of Philadelphia County.

Between the two factors, the city says pack sales in the first year of the tax will plummet from 65.1 million to 41.6 million.

It’s from this number that the city multiplies by $2 to arrive at $83 million in projected revenue.

Answering the doubters

Mallya is confident that his projections will stand the test of time.

“Whether we look at research at the state level, the city level or even internationally,” he said, “these estimates are very, very consistent.”

Mallya says those who doubt the estimates are often those who “don’t want to see these price increases go into place.”

“There’s often this conversation about, ‘people will just drive to Delaware to buy their cigarettes,’ or ‘they will stock up for what they need over the next three months,’ but that’s not how smokers generally smoke,” he said. “This discussion about people radically changing isn’t really consistent with what we know about how people generally respond.”

City finance director Rob Dubow said his department wrestled with and approved the numbers over a year ago, before city council passed the tax.

“We always push whenever we get numbers, but…there are really compelling reasons for these numbers,” said Dubow.

As each year passes, the city expects the cigarette tax to generate less revenue.

FY15: $83.2M (if implemented by the beginning of the fiscal year, which began July 1st)FY16: 77.5MFY17: 75.1MFY18: 73.9MFY19: 72.7M

A report published in March 2014 by the Tax Foundation found that smuggled cigarettes account for 1.1% of the total cigarettes smoked in Pennsylvania.

A fact sheet released by Tobacco Free Kids in 2013 found that every state that increased cigarette taxes received more revenue than it would have collected without that increase, this “despite the lost sales from related smoking declines and despite any increases in cigarette smuggling or other tax-evasion.”

A 2012 analysis by Tobacco Free Kids presented a list of quotes from internal tobacco company documents revealing Big Tobacco’s admission that raising cigarette prices is one of the most effective ways to prevent and reduce smoking, particularly among children.

Mallya says that, in addition to providing revenue for schools, the tax will be a boon to the general health of city residents – specifically the young and the poor.

“The research is clear on that,” Mallya said. “This is a public health slam dunk.”

In conjunction with the city’s other tobacco control strategies, the department of health expects the tax to save $50 million per year in healthcare costs and offer approximately $20 million in productivity gains.

“People who are smokers are less productive when they are at work,” said Mallya, “and they are less likely to be at work consistently.”

Asked to analyze Philadelphia’s projection, Vince Willmore, spokesman for Tobacco Free Kids, wrote:

“Their estimates strike us as reasonable. Based on science and experience, we believe the proposed cigarette tax increase in Philadelphia will be effective both at raising substantial revenue and reducing smoking, especially among kids.”

The Chicago story

Remembering that Philadelphia’s estimates are based, not on actual sale receipts, but on a limited sample survey, it’s useful to view Philadelphia’s expectations in context with other cities that have made revenue projections based on real cigarette sales.

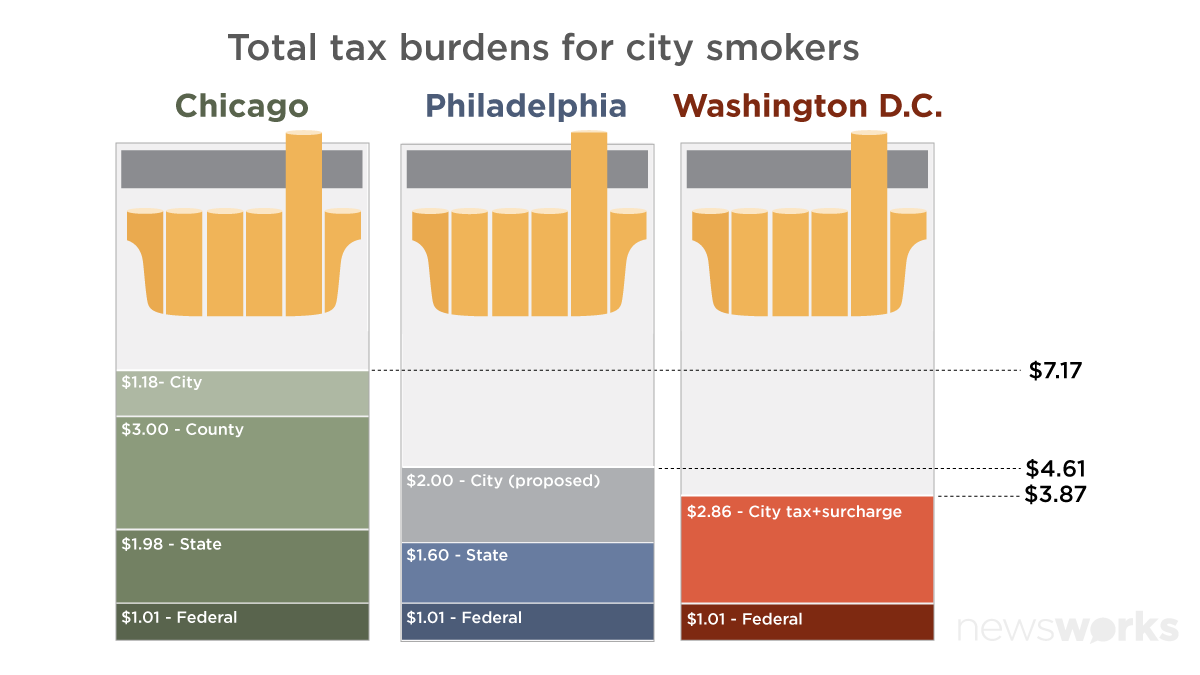

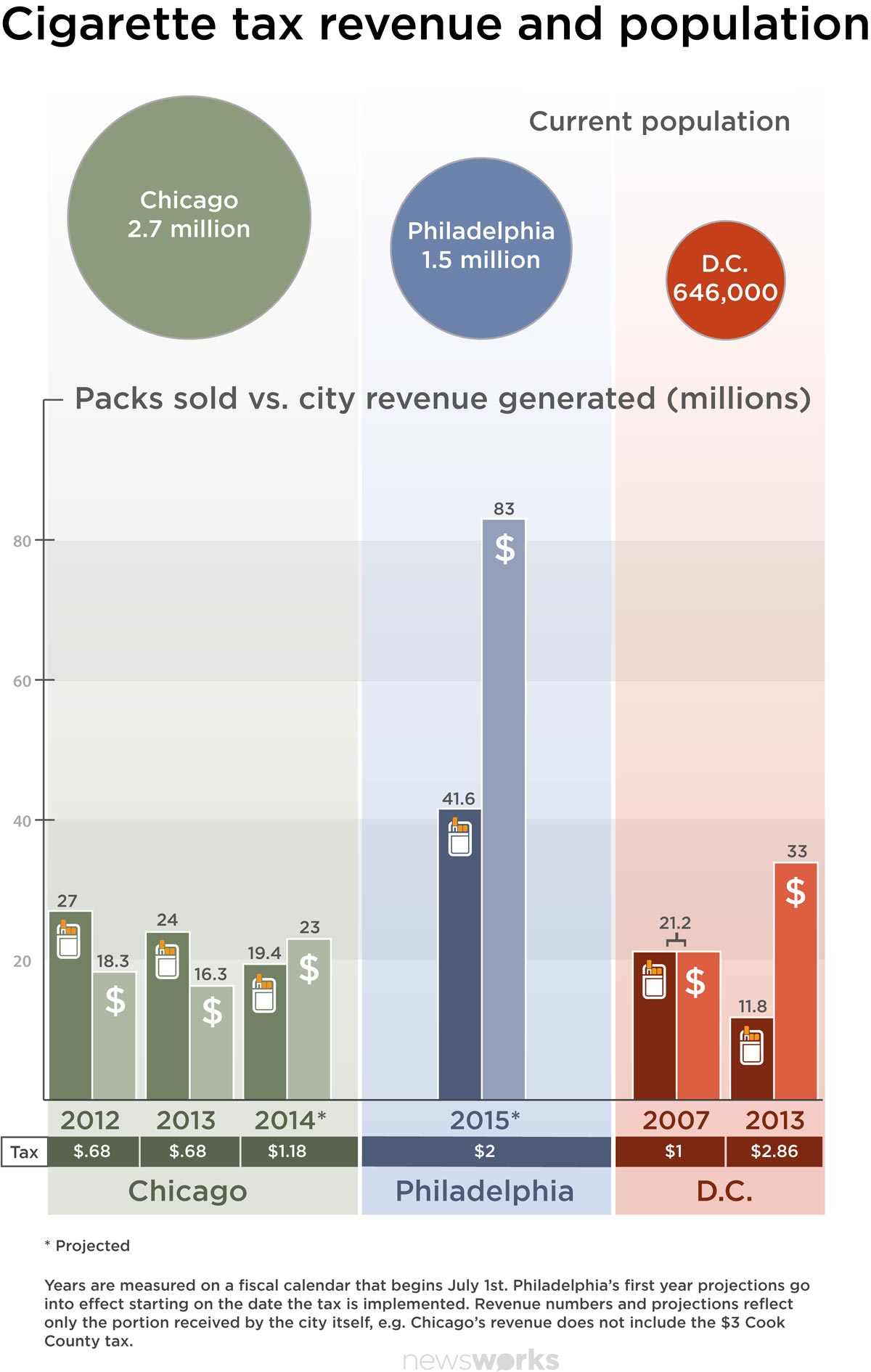

Chicago, population 2.7 million, currently faces the steepest cigarette tax burden in the nation.

In November of 2013, the city approved a 50 cent per pack tax increase, bringing the total city tax to $1.18 per pack.

In addition to this, Chicago smokers must pay $3.00 to Cook County, $1.98 to the state of Illinois and $1.01 to the federal government per pack of cigarettes.

This makes Chicago’s total tax burden $7.17 per pack.

(By comparison, even if the $2 pack tax passes, Philadelphia’s total cigarette tax burden would be $4.61 per pack.)

In 2012, with a 68-cent city cigarette tax, receipts show that 27 million packs of cigarettes were sold legally within the city of Chicago, generating $18.3 million.

In 2013, still with a 68-cent city tax, Chicago collected taxes on 24 million packs, generating $16.3 million.

This year, with the 50 cent tax that’s increased the city’s burden to $1.18, city officials estimate the number of packs sold will drop to 19.4 million packs, but generate $23 million.

It’s worth underlining this point: Chicago, a city with almost double Philadelphia’s population expects to collect taxes on fewer than half as many packs of cigarettes this year.

Sources within Chicago’s city government who declined to be named disagreed about the prevalence of cigarette tax evasion in the city. One source said the problem was “rampant,” another said there is no significant illegal tax evasion.

In a 2010 research paper, University of Illinois professor David Merriman found that 75 percent of the packs of cigarettes littered on the streets of Chicago did not bear the city’s tax stamp.

Chicago’s southeastern edge borders Indiana, where city smokers can currently save $5.17 per pack.

Comparatively, if the increase goes into effect, Philadelphians hoping to find the best deal could leave the county or travel to Delaware to save $2 dollars per pack.

Again, if the increase goes into effect, buying cigarettes in New Jersey would save Philadelphians 89 cents per pack in taxes.

Merriman called the city’s 30 percent avoidance rate estimate “optimistic.”

In a 2013 report focused on New York City, Merriman found that about 50 percent of littered packs didn’t bear the city tax stamp.

In a 2011 report that analyzed five cities including Philadelphia, Merriman found that 27 percent of littered packs did not bear a city tax stamp.

Mallya questioned Merriman’s methodology and emphasized that the disparity between Philadelphia’s and Chicago’s projections rests in the substantial difference between each city’s total tax burdens.

Simply put, he said a $7.17 tax burden will push way more people to evade than a $4.61 burden.

“I think majority of that difference between Chicago and the numbers for Philly…is because of the significantly higher price there,” said Mallya.

Washington D.C.

The District of Columbia, population 646,000, imposes a $2.50 per pack tax on cigarettes in addition to .36 cent surcharge (which will increase to .40 cents in October).

In 2013, Based on a $2.86 city cigarette tax burden, D.C. collected taxes on 11.8 million packs of cigarettes, generating roughly $33.9 million.

In 2007, when D.C.’s cigarette tax was $1.00, the city – then with a total population of roughly 574,000 – generated $21.2 million in revenue on 21.2 million packs.

Comparing 2007 with 2013, D.C.’s cigarette tax revenue grew by $12.7 million even as it collected tax on 9.4 million fewer packs.

D.C. borders Virginia, which taxes cigarettes at .30 cents per pack, the lowest rate in the nation.

Hypothetical per capita exercise

To break down these numbers further, let’s divide the total number of packs sold by the total populations of Chicago, D.C. and Philadelphia in 2013.

It should be noted that these are hypothetical numbers that assume that every man, woman and child in each city is a regular smoker. They also assume that only Philadelphians buy cigarettes in Philadelphia.

Both are obviously untrue, but the exercise gives us a rough portrait of a each city’s smoking habits as a total entity.

In Chicago, 24 million packs among 2.7 million Chicagoans equals a per capita rate of 8.88 packs per year per person.

In D.C., 11.8 million packs among 646,000 Washingtonians equals a per capita rate of 18.2 packs per year per person.

In Philadelphia, city officials estimate that 65 million packs were sold last year. Dividing this by 1.5 million Philadelphians equals a per capita rate of 43 packs per year per person.

Looking forward, if the number of packs sold drops as the city expects to 41.6 million, the per capita rate would be 27.7 packs per year per person.

Analyzing these numbers this this way accentuates the radical differences between Philadelphia’s smoking rates and those of Chicago and D.C.

The disparity here could be attributed to a number of factors.

Chiefly, it spells out what’s been long known: that Philadelphia has the highest smoking rate of all big cities in the U.S. (See page 60 of this Philadelphia Department of Public Health report.)

But the disparity could reflect other truths.

For one, it could support the notion that the numbers for Chicago and D.C. have been drastically deflated due to tax evasion

It also could suggest that the survey upon which Philadelphia has made its estimates has started from an inflated number.

That answer won’t be known for certain until a year’s worth of true collection data becomes available, which, of course, won’t occur unless Harrisburg authorizes the tax.

69th Street

Beyond the city limit, Helen Kim manages a bodega a stone’s throw from the 69th street SEPTA terminal in Upper Darby.

The tax will bring her extra business at first, she says, “but in the long run it won’t because people are going to quit smoking overall I think.”

It’s just too expensive, she says.

“They’re already quitting now, when it slowly rolls like ten cents here and there, so they’re going to quit in the long run. That 2 dollar tax is going to really hurt.”

Kim repeated a concern among many bodega owners I spoke with, one that’s frightening many on the Philadelphia side of the line.

They say cigarette sales don’t generate a large percentage of a store’s profits, but they get people in the doors, who then buy drinks, snacks and other items that drive a bigger profit margin.

Armani Pritchett, 17, is one of the customers that sellers in Philadelphia are afraid of losing. Although underage, he says he has no trouble buying cigarettes from corner stores in his Southwest Philadelphia neighborhood.

But if the $2 per pack tax comes?

“I quit. I’ll quit if they go up two dollars, couldn’t do it. They already $6.50. I wouldn’t be able to do it,” he said, as we talked in Upper Darby. “Or I’ll come up here.”

For Kim, it’s only a matter of time until she says things will even out. Sooner or later she believes a tax increase will come that affects her shop.

“The government always needs money. It’s like, if Philly can do it, why would Upper Darby avoid the tax,” she said. “They could just add the tax and be like, ‘Hey, it’s a Philly thing and this area is going to have it. We need the money for schools, the roads, you know, whatever reason.'”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.