Can the ‘Boston Miracle’ deter gun violence in South Philly?

Listen-

A memorial for Nasir Slaughter, a 17 year-old who was gunned down in August, 2013, is shown. He was killed over a neighborhood dispute. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

A vacant lot in South Philadelphia

-

Keri Salerno is director of re-entry strategies and outreach for the city of Philadelphia. (Nathaniel Hamilton/for NewsWorks)

-

Ruben Jones helps men on the difficult path away from gangs and toward a less dangerous life. (Nathaniel Hamilton/for NewsWorks)

Philadelphia gathered a network of law enforcement organizations to implement a new strategy of gang deterrence. It pushes cops to creatively focus their limited resources on the people who commit the most crime.

The street violence that fills the evening news in Philadelphia can seem random. A personal beef here, a drug deal gone bad there. But police say gangs, and criminal street crews account for much of the violence.

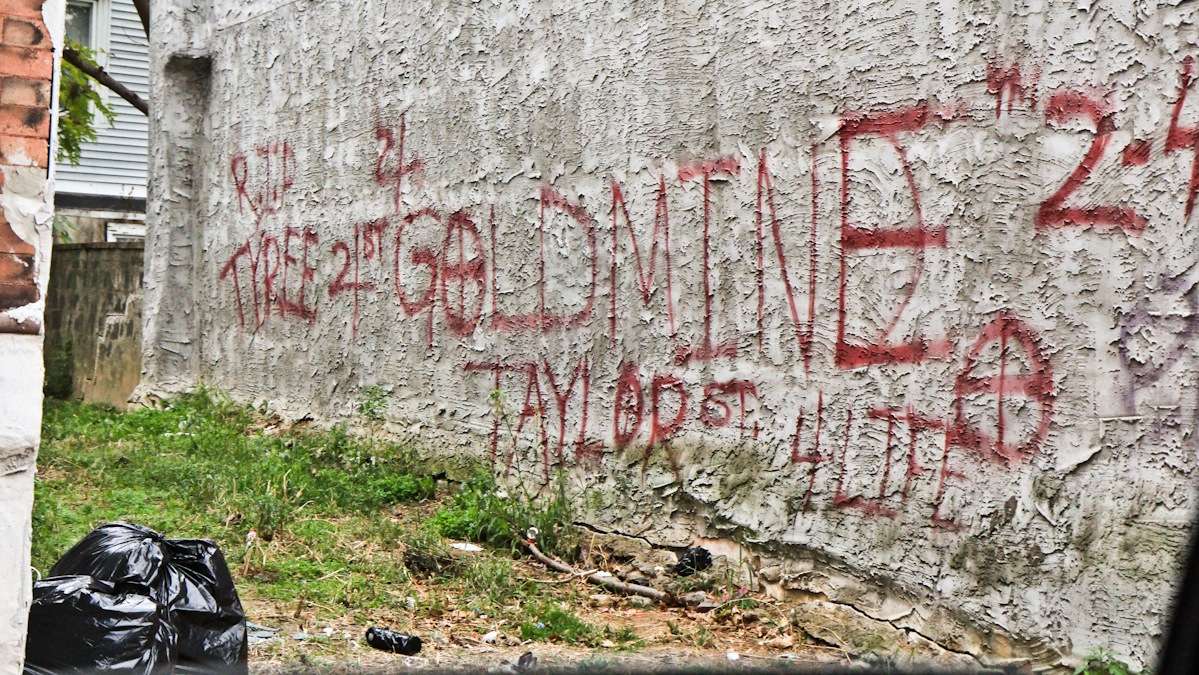

In South Philly, there’s the 5th Street North gang, 5th Street South, 8 Ball on 18th Street and M16’s. Where gangs hang, gun shots often ring out. Philadelphia police officer James O’Neill stands in front of a candle-and-stuffed-animal memorial at 1700 Taylor Street, a tribute to a casualty of a neighborhood dispute.

“Four people were shot, and one of them passed away. The other three were OK.” O’Neill says simply, “A lot of people were shot. Too many.”

O’Neill is part of the South Gang Task Force — he’s the daily street-level piece of a larger new strategy called Focused Deterrence. It’s based on the idea that there aren’t enough cops to crack every case or penetrate every gang, but with targeted pressure and the right approach, some gangs can be induced to put down their guns. It’s happened in other cities.

A ‘miracle’ in Boston — focused deterrence

Criminologist David Kennedy developed the crime-quashing strategy in the 1990s. It’s also been called Operation Ceasefire or The Boston Gun Project. In that city, youth homicides dropped 63 percent after the strategy was adopted. Some started referring to it as the “Boston Miracle.” Kennedy says the strategy pushes law enforcement to focus its limited resources.

“In most cities, if you identify all the groups and everybody in them, they will represent under half a percent of the city’s population, and they will be associated with 60, 70, 75 percent of all homicides as victims or offenders or both,” Kennedy said.

Some describe it as the opposite of the controversial “stop and frisk” policing method. Kennedy admits his approach requires a lot of work to execute, but he says it’s common sense: Focus on the people committing the most crime.

“When you look at homicide and most gun crime, it turns out to be enormously concentrated among remarkably small numbers of very active street groups in the particular neighborhoods,” said Kennedy. “These are gangs and drug crews and sets and whatever you may want to call them.”

To implement Kennedy’s vision, Philly gathered a network of law enforcement organizations, including the city police, the District Attorney’s Office, the ATF, FBI and U.S. Attorney’s Office. A few months ago, all those agencies gathered in a room — with gang members. That’s right, all in one room. The crime-fighters let the gang members know they can’t keep shooting, and they told them the first gang that opens fire will feel some serious heat.

They were told, as Officer James O’Neill puts it: “If anyone pulls the trigger — their whole group is going to go down, and we’re going to focus on them, and we’re going to keep coming and coming until the violence stops.”

Some in Philly law enforcement prefer to call them “groups,” to avoid comparisons to more established and well-known gangs such as the Bloods and the Crips. Crimes driven by these affiliations aren’t always publicized, so it’s easy to overlook their presence. Call them what you will, from beat cops to the DA’s Office there’s agreement that Philly has a problem.

But the strategy also uses positive peer pressure to try to convince gang members to stop shooting. Of course for the Focused Deterrence strategy to work, it needs teeth. Caroline McGlynn of the DA’s office says that when there’s a shooting, the coordinated approach keeps the pressure on individual members of the group who pulled the trigger.

“If they’re on probation or parole, they have to go see their probation officer immediately. If they owe child support, their case kind of goes to the top of the list. If they have a bench warrant outstanding, they’re picked up,” McGlynn said. “Basically they’re put on top of the list for everyone’s enforcement.”

That’s the stick in this strategy. But there’s also a carrot. To draw gang members out of that life, Focused Deterrence operates on the premise that not everyone in a gang wants to be there — and that those members would be willing to leave the violence but are scared to put down their guns. So at the call-in — where the gang members and law enforcement are all in the room together — the guys are offered help going back to school or getting a job. They hear from crime victim families, and they’re told that they are valuable human beings.

The front man for gang outreach

Ruben Jones is the man the gang members call if they decide they want to leave the life behind. He has seen the faces of the men at the call-ins when community members spoke, including a woman who lost her son to gun violence. “I could see guys welling up and fighting back the tears,” Jones said.

Jones grew up in North Philadelphia and served 15 years in prison for robbery and aggravated assault. Now he’s an independent contractor being paid to connect gang members with social services under the Focused Deterrence umbrella.

He says so far 16 people have asked for help: “Nine of them have been placed in employment. Nine of them have been referred to drug and alcohol treatment. A few more have been referred to education — both GED and higher education.”

Jones says those relatively small numbers still are significant. He says convincing one person to reject violence could save two, three, four people from becoming the next victims.

Jones cites a Robert Frost poem, “The Road Not Taken,” and says the power of peer pressure should not be underestimated. If everyone else in the neighborhood is hanging out on the corner, it’s tough to be the guy who goes to school or work instead. Jones says getting a guy in the room for a call-in can be a turning point. “They’re put on notice that, ‘Hey this is what’s going to happen.’ It gave him an out. It said, ‘Hey, listen. I don’t want that. Let me make this choice.’ And after making that choice, to walk away from that lifestyle and seek help, because it’s easier for him to really start to dream again and pursue those dreams.”

Concentrating police in targeted areas has been tried before in Philadelphia. There have also been efforts to grab kids before they join gangs. But there hasn’t been such a large, coordinated multi-agency push that includes social services and singles out gangs and specific gang members.

An effort coordinated citywide

In implementing David Kennedy’s model, Philadelphia’s trying some creative approaches, says police Lt. Gary Ferguson — even going after mundane violations such as illegally connecting to electric or gas lines. “We do everything in our power to — if these guys are going to use guns or the threat of violence — to inconvenience them,” Ferguson said. “PECO and PGW have disconnected the services of over 100 people in reference to this Focused Deterrence program.”

Ferguson says, for the officers risking their lives on patrol, they know there’s an entire united infrastructure ready to clamp down if a gang member pulls the trigger.

Keri Salerno, director of re-entry strategies and outreach for the city of Philadelphia, says the city has provided $150,000 for social services in the Focused Deterrence strategy. She insists this is not another general anti-violence program. She points out it is voluntary and it includes an impressive collaborative effort by law enforcement, community and social service organizations. The Maternity Care Coalition, Goodwill and the Community College of Philadelphia all participate.

Salerno says there’s another thing that makes this strategy stand out — it’s the guy in the tie sitting next to her: Reuben Jones.

“Reuben is the one that helps everyone through this referral process,” she said. “He physically walked someone over to [Community College of Philadelphia]. He’s taken guys up to 440 North Broad to try to figure out what’s going on with their high school credits, if they can get a diploma. There’s one point of contact, one phone number, one guy.”

So why don’t these guys just leave the life behind and sign up for classes or treatment on their own? Jones says some of the barriers are mental. “It’s just when you live a lifestyle — first of all this person has a young daughter and he has a disabled mother — so in some ways he felt a little bit helpless. So the easy way was to just be on the street corners doing what everyone else was doing. That’s the easy way out,” Jones said.

Jones helps them along the more difficult path. And he goes on with the knowledge that some will turn down the offer, while others will reach out for help only to go back to their old ways. This is a hard part of the job: not getting thrown off by efforts that don’t turn out well. Instead, the Focused Deterrence team in Philly is concentrating on the relatively small number of successes while plowing along spreading the message and trying to help one more person.

Examining the big picture

There are great hopes that the many-pronged approach could make Philly safer. “If it goes well it could be a historically huge turning point for this city and I want to be a part of it,” said Ruben Jones, the man gang members call for help. This crime-fighting approach has seen success in other cities. And after just six months in Philly there are positive signs when it comes to guns: Shootings in South Philadelphia are down 43 percent compared to this time last year and the number of homicides has dropped to seven from 15. But for these early numbers to really matter in the city’s big picture, they must continue through the years as young parents decide to stay and raise families and empty nesters move back into the city.

David Kennedy says he’s impressed by Philly’s implementation of the strategy so far. Police say there are already stories circulating about gang members who say they don’t want to be on “The List,” for fear of targeted enforcement.

Now it’s time to put numbers to the anecdotes. Caterina Roman helped with the implementation of the strategy in Washington D.C. about a decade ago when she worked for the Urban Institute. She’s now an assistant professor in the Department of Criminal Justice at Temple University and is advising Philly in its application of Focused Deterrence. She says compared to other violence prevention strategies that attempt to change the norm, this one is law enforcement based. “That uses the notions you know back — Jeremy Benthem and the great philosophers that talked about deterrence. That used the idea of deterrence to really get those high level offenders to know we’re going to be on top of you if you don’t put down the gun,” Roman said. Over the next three years Roman will be use a $300,000 federal grant to examine Philadelphia’s implementation of Focused Deterrence to evaluate the strategy and some of the alternative levers Philly is trying out, such as coordinating with PECO and PGW to shut off illegal service to gang members’ homes. “Looking at child-support enforcement orders and who has open child-support enforcement issues and focusing on that. Not a lot of other jurisdictions did that. So just to show even, and document, the types of levers that Philadelphia is pulling. And then show here’s the size of the impact and if other jurisdictions were to do the same I think a few years from now it would be clearer — it’s called a logic model — what pieces of Focused Deterrence are really necessary,” she said.

Roman says she’s also using the grant to develop lists of group members in at least one other jurisdiction in the city so she can compare it to South Philly where Focused Deterrence is being used and measure its effectiveness. She says this “isn’t just another evaluation of Focused Deterrence. This is an evaluation that will help us understand the mechanisms of the program. What might be working and what might not be working in the collaboration and the types of aspects of a program that can really be useful to jurisdictions around the country that are thinking about replicating the model.”

The video below is a rehearsal for the talks with the gang members. It was provided to NewsWorks by the District Attorney’s office.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.