Can a diverse neighborhood now integrate its schools? In Mount Airy, it’s happening.

Increasing numbers of catchment families are enrolling in their local District schools in this section of Northwest Philly.

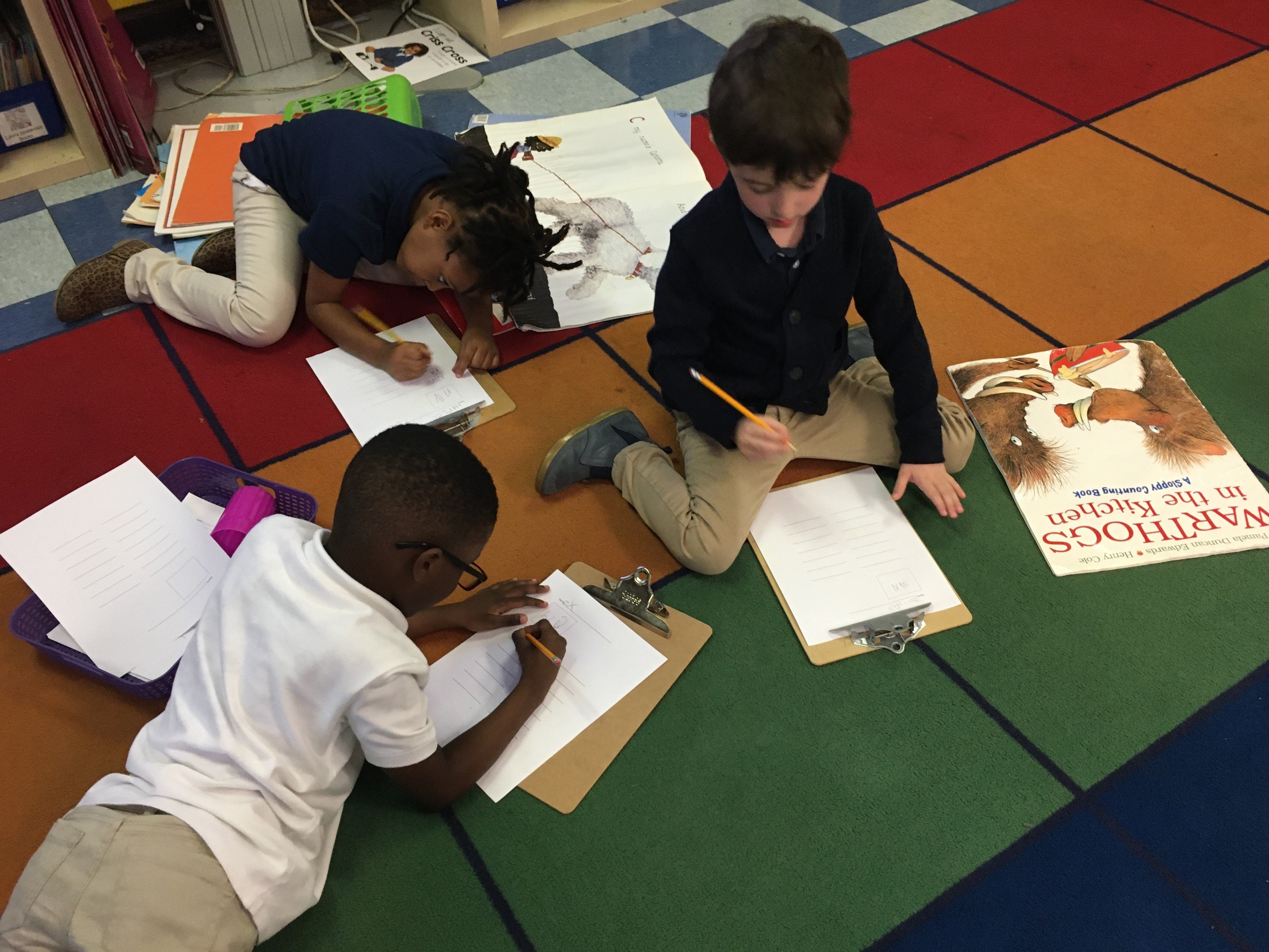

Best friends play at Houston school in Mt. Airy. (Photo by Huntly Collins)

This article originally appeared on The Philadelphia Notebook.

For decades, Philadelphia’s liberal Mount Airy neighborhood has faced an uncomfortable truth: while the area is racially and economically integrated and proud of it, Mt. Airy’s public elementary schools are predominantly black, with large numbers of low-income students. But that is now changing at the two K-8 schools in West Mt. Airy.

At Henry W. Houston Elementary, where about 80% of the students are black and most are low-income, 22 percent of the school’s 55 kindergarten students this fall are white, up from just 6% last year. At the same time, the school is beginning to attract more black middle-class families who once opted for charters, other public schools or pricey private-school alternatives.

“On the first day, everyone was welcoming,” recalled Kate Bryant, an educator and white parent who enrolled her daughter Alice, 5, in Houston’s kindergarten this fall. She and her husband Peter are products of public education and have fond memories of walking to their neighborhood public school in upstate New York.

While having racially integrated neighborhood schools may not be on the top of the agenda of School District officials now beginning work on a comprehensive plan to reorganize the entire public school system, it is on the mind of a growing number of young families in Mt. Airy, including the Bryants.

Even when Alice was a toddler, the couple began talking to other parents in their Mt. Airy daycare center about giving their daughter the opportunity to walk to her nearest public school. They helped organize “Families for Houston,” a nonprofit that touts the school’s educational opportunities, raises funds, and encourages neighborhood parents to give the school a fair shot.

“We want the whole community to see the great things happening at Houston,” Bryant explained one sunny Saturday afternoon as she and Peter, a lawyer, relaxed with their two children in their East Mt. Airy backyard. The couple said that Alice, a lively child with big blue eyes, is thriving in her small kindergarten class at Houston with an excellent teacher who engages children in small-group learning.

Sarah Gibson, an African-American parent who works as a lactation counselor at the nonprofit Maternity Care Coalition, is equally excited about Houston. She enrolled her daughter Terrah in its kindergarten last year after considering and rejecting Houston for an older daughter nearly a decade ago. “What I saw was a lot of chaos,” she said as she recalled her visit to Houston in 2011.

Today it’s a different story. The school’s hallways are orderly and Terrah, now in first grade at Houston, has made huge strides, particularly in math, Gibson said. “From last year to this year, my child is learning on a level I would never have imagined,” she said. “I think the school is only going to get better.”

Slowly, one family at a time, Houston has begun to win back families like the Bryants and the Gibsons by shedding its past reputation for low student achievement, student disciplinary problems and unsafe corridors. While it is still racially imbalanced, the lower grades are beginning to reflect the neighborhood’s demographics. That’s evident on the Houston playground where children from white and black families play together both during school and on weekends.

Building community and parent support

Incoming parents at Houston embrace racially integrated schools for their children, but they also want to support public education, avoid hefty private-school tuition and take advantage of the many educational improvements at the school in recent years under the leadership of LeRoy Hall, Jr., Houston’s dynamic principal who is now in his sixth year at the school.

“If you build it, they will come,” said Hall, 39, during an October interview in his office. He characterized himself as a “servant leader” focused on improving academics, school climate and parent engagement — actions necessary to regain the confidence of any community, whatever its makeup. “If we build a quality school, people will want to put their kids there,” he said.

While results on the state PSSA tests, given to third through eighth graders, are still well below the statewide average, Houston’s students are exceeding the state’s growth standards in both language arts and math. According to the Philadelphia School District’s own testing, reading scores in the early grades have shot up. In 2017-18, for example, 56% of students in kindergarten through second grade were reading on grade level, up from 21% the year before.

Students at all grade levels now study grammar. “Language is power,” explained teacher-leader Jennifer McKenzie, citing the pioneering work of Brazilian literacy educator Paulo Freire. Every day, McKenzie makes a one-hour commute from her home in Collegeville. “I wouldn’t want to work anywhere else,” she said.

At Houston, classes are relatively small and students typically work in groups, each doing something different. In a seventh grade math class, for instance, the teacher worked on equations with eight students on a whiteboard, while 17 other students worked in small groups on different math skills.

Houston’s students are also reaping the benefits of an army of dedicated citizen activists for which Mt. Airy is known. Besides having dedicated teachers in a staff that is stabilizing after a period of churn, students get additional support from some 40 community volunteers, many of them retirees, who read to children, provide tutoring, and help run the school library. “I get pleasure out of coming here to help students pick out books,” said Maynard Seider, 76, a retired sociology professor, as he checked out books to a third grade class, which visits the library twice a week.

In the cash-strapped system, Houston gets the supplies and equipment through partnerships. Home Depot donated the orange buckets used as drums in the music room. The wooden picnic tables and chairs in the new STEM garden were all built on-site in one day by Jersey Cares, a nonprofit group. The flowers in the planters in front of the school and the “eco bricks” in the STEM garden — made of single-use plastic — all came courtesy of Weaver’s Way Co-op, a member-owned grocery begun in Mt. Airy.

The Power of Three

Student discipline at Houston, once punitive, is now restorative. Instead of being sent to detention, students go to the “centering room” where they learn to talk through their issues. At 10 a.m. every day, the entire student body stops what it is doing and pauses for a “mindfulness moment,” which helps students stay focused. Houston teachers are now being trained by volunteers in how to integrate mindfulness meditation into their regular classroom routines.

What Houston calls “The Power of Three” — take care of yourself, take care of others, take care of your school — has infused the school’s culture. Nearly every student, from kindergarten on up, can recite it and knows what it means. Among other things, the mantra has gotten students to pick up trash on the playground.

Hall, who is biracial and identifies as African-American, has watched Houston’s recent success in attracting more white families. And while he’s encouraged that the student body is beginning to reflect the diversity in Mt. Airy, he wants to make certain that Houston retains its African-American families. “I want all the people who look like me to stay, and I want others to come,” he said.

Alison Cohen is a white parent who lives next door to Houston. She and her wife have three children, the oldest now in first grade at Houston. The couple transferred their daughter to Houston after she spent a year in kindergarten at nearby Henry School, West Mt. Airy’s other public K-8 elementary school. “For me, it never felt right that we were sitting next to Houston and not using the school,” Cohen said. “The implicit message was, ‘This school is not for you.’”

Cohen’s change of heart developed as she came to terms with what she called her own internalized racism, a topic she explored in depth by listening to the podcast, Integrated Schools, (www.integratedschools.org). The program, which attracts a mostly white audience, discusses the importance of school integration, and helps educate parents about racism and what can be done to eliminate it. “White people need to fix the problem because we created it,” said Cohen, an environmental activist who runs a business that supplies bicycles to large cities, including Philadelphia.

Undoubtedly, race-based stereotypes have played some role in what has amounted to white flight from Mt. Airy’s public schools in the past. But given the neighborhood’s history of standing up to blockbusting, panic selling and redlining during the 1950s and 60s, it’s likely that other factors have played a greater role in siphoning off white families.

One of those is the large number of private-school options in Philadelphia, including its well-regarded Quaker schools. Public selective-admission schools, such as Julia R. Masterman, which starts in 5th grade, have pulled older students. In recent years, the rise of charters, which now enroll more than 65,000 of the city’s 200,000 public-school students, have been an additional drain.

Chronic state underfunding of education has also led parents to look for alternatives. For many years, Houston had to shutter its library because there was no one to staff it and the books were outdated and tattered, a turnoff for prospective parents. And it hasn’t helped that, in the past, Houston had a reputation for student disciplinary problems, which sometimes spilled into the street. But those days appear to be long gone.

Henry school provides a roadmap

As it begins to attract and retain more neighborhood children, Houston is taking a cue from nearby Henry Elementary, which has built a talented teaching staff and worked hard on parental engagement.

As of 2017, the latest year for which statistics are available, the Henry catchment area, all of it on the west side of Germantown Avenue, was home to about 6,000 people, 39% of them white and 49% black. Last year, 24% of Henry’s 511 students were white and 65% were black – numbers closer than Houston’s to the neighborhood’s racial demographics.

“We’ve been working at it for a long time, at least 10 years,” said Greg Anderson, a white parent who lives in the Henry catchment area. He has two children enrolled at the school and another who transferred from Henry to Masterman. Anderson is active in Henry’s PTA and in a program called “Considering Henry,” in which current parents meet in small groups with prospective parents to answer questions and share their own experiences.

Since 2015-16, about half of Henry’s students have come from its catchment, but that number is inching up. Last year, the school’s two kindergarten classes were filled with students who lived in the school’s catchment area, with more than 100 out-of-catchment applicants on a waiting list. Over the same period, total enrollment has remained steady at around 500 students every year.

“We have a lot of local families who are incredibly invested in our school,” said Katherine Davis, who became principal of Henry last March. Davis is biracial and herself a product of Henry School, which she attended in kindergarten through 4th grade. “This is home for me.”

Houston, which now enrolls 374 students, faces more daunting challenges. Sixty-two percent of its student body is economically disadvantaged compared to 43% at Henry, according to the state. Studies have shown that students from impoverished families often bring childhood trauma with them into the classroom, which interferes with learning and depresses scores on standardized tests.

Houston’s catchment includes parts of both West and East Mt. Airy. More than 11,000 people live within the area, about twice the number in the Henry area. Even so, only 48% of Houston’s student body came from its catchment area last year, down from 62% in 2015-16.

‘A strong community has a strong public school’

Houston’s catchment is fairly balanced between black and white residents, but its student body is not. In 2017, the latest year for which data are available, 48% of the people living within Houston’s boundaries were white and 44% were black. By comparison, 81% of Houston’s 345 students last year were black and just 4% were white.

“Public schools have been the great melting pot of society,” said Steve Stroiman, 75, a retired teacher and Mt. Airy resident who has long sought to mobilize Houston-area residents to support their local public school. “A strong community has a strong public school. To abandon public schools is to abandon our civic obligation.”

One rainy November night, Houston’s principal came to speak to the neighborhood town watch that Stroiman coordinates. Despite the bad weather, more than two dozen neighbors crammed into a living room to hear from Hall and three other Houston administrators.

Nattily dressed in a striped suit with a leopard-spotted pocket square, Hall settled into an armchair and talked about growing up in Pittsburgh. He is the son of a white mother and a Jamaican-American father and was raised by his mother. They were poor but Hall hit on a way out of his situation. He would either become an NBA basketball player or a teacher. Education won.

He did well in school, enrolled at Indiana University of Pennsylvania, and then got a master’s degree at the University of Pittsburgh. He is now working on a doctorate in educational leadership at Drexel University.

Hall’s first job out of college was as a math teacher at a charter school in Pittsburgh that was in danger of being shut down by the state because of low academic achievement. While he was teaching there, under the leadership of a new principal, students began making significant gains and the charter was named a Blue Ribbon School by the U.S. Department of Education.

At Houston, Hall would like to see a similar turnaround. His focus, he said, is not on the numbers needed to achieve racial balance but on providing a quality education for every child. So far, Hall’s efforts have drawn rave reviews from both parents and community leaders.

Under his watch, Houston has added music to the curriculum and beefed up its STEM classes. Teachers meet in small groups every morning to break down core curricular requirements into small chunks that students can master. Hall set up a “Houston bucks” reward system for good behavior that allows students to shop in the school store. Students go on trips to local colleges and are encouraged to wear shirts bearing college logos on Fridays.

On a crisp Sunday morning, a dozen or so Houston parents and other volunteers gathered to clean and repair the playground. Sarah Wieland, whose son is in third grade, swished a paintbrush up and down a wooden fence post, coating it with linseed oil to protect the wood through the winter.

Wieland, a white parent who lives a few blocks away, pulled her son out of a prestigious private school to enroll him at Houston where she said he is now getting the attention he needs. “He is a high-energy boy and his teacher makes him and the other high-energy boys feel good about themselves,” she said.

Nearby, Claire Murphy, another parent, tended to the “kindergarden,” planter-boxes filled with lettuce, carrots, broccoli, kale, rosemary and other herbs, all planted by kindergarten students. A playground just for them has pint-high basketball nets and hop-scotch designs that teach the alphabet, numbers and geometric shapes. The older children have their own playground with climbing equipment and lots of space to run.

On the west side of the school, Christine Bush, Houston’s STEM teacher who lives a few blocks away, was busy mulching the STEM garden, where students from kindergarten through eighth grade study sciences. The garden is filled with native plants, including those that attract bees, butterflies and hummingbirds so students can learn about pollination. “Students basically practice the art of being scientists by asking questions and wondering about the natural world,” Bush explained.

While many Mt. Airy families make use of the school’s playground, it’s been frustrating to Hall that few of those same families have set foot in the school. Hall’s new marketing strategy is a flyer that reads, “If you like the playground, you’ll LOVE the school!” It invites parents to visit Houston for one of its monthly tours offered throughout the school year.

As more white families join the Houston community, the school is wrestling with a difficult question: How do white parents avoid the impression that they have come to “rescue” the school from being poor and black?

To avoid that, Houston’s newly revived Home and School Association (HSA), which has been officially registered for the first time in years, has two co-chairs, one white and one black.

Emily Kathleen Pugliese, the white co-chair, said she took the job on the condition that the leadership be shared with a black parent. “I didn’t want it to seem like I was coming in to ‘fix’ the school and that I had all the answers,” she said.

Monique Smith, an African-American parent and the other co-chair, met Pugliese because both their sons attended Houston’s after-school program. An experienced teacher who is now an administrator in the Mastery Charter School network, Smith jumped at the opportunity to share leadership of the HSA. “We wanted the leadership to look like the building,” she said.

While efforts to diversify Houston are now showing results in the lower grades, the big question is whether the diversity will hold as students progress to higher grade levels. At both Henry and Houston, the proportion of white students sharply declines by middle school.

At Houston last year, for instance, there were 13 white children in the 4th grade, but just four 5th through 7th grades and none in 8th.

White parents such as the Bryants are well aware of the pattern. They hope to keep their daughter Alice at Houston as she moves to higher grades and vows to do so “if she is thriving,” Kate said.

Houston is just one school, but the drive to integrate it mirrors the challenge the entire country faces as it confronts growing economic inequality, re-segregation of public schools, a demographic shift to non-white majority populations and a deepening political divide. As Stroiman put it: “Public schools are either going to be a part of our future or not. They are either going to save our democracy or just become repositories for the poor.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.