Camden’s success with gunfire surveillance has Philly officials looking at audio program

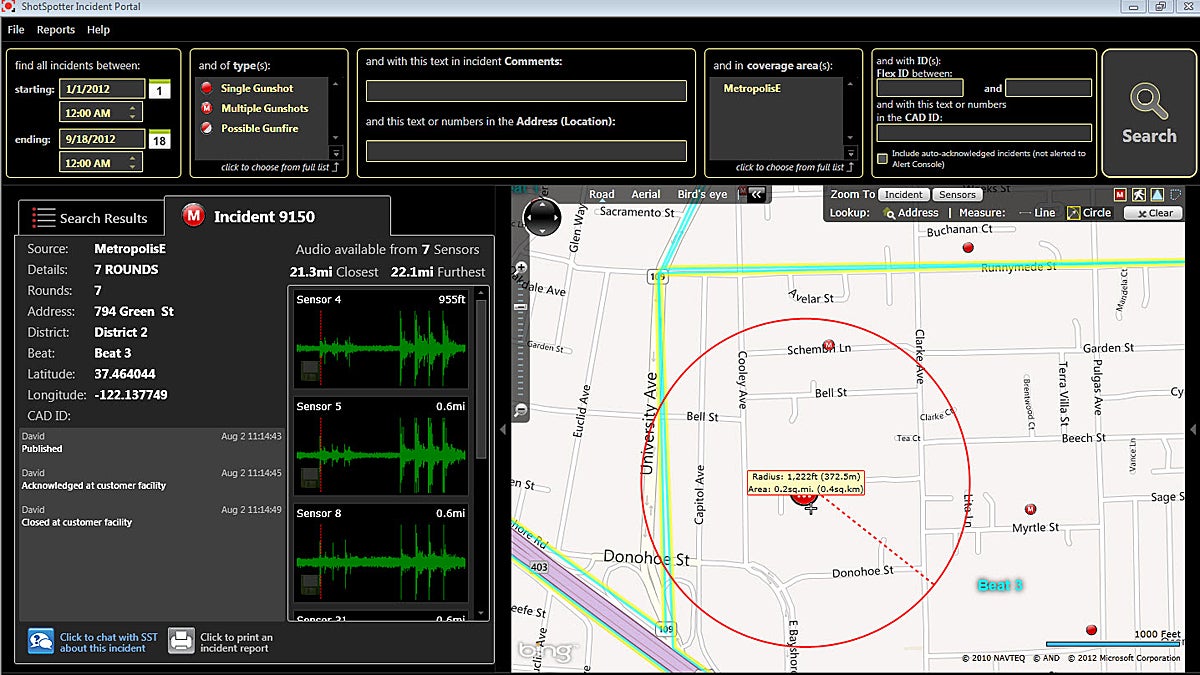

This image shows the screen an officer would see in their cruiser while using the new ShotSpotter technology. (Image courtesy of ShotSpotter)

A new form of audio surveillance in Camden is credited with helping cut gunfire by almost half over the last year — and some city officials want to bring the system to Philadelphia.

The ShotSpotter system uses outdoor microphones to automatically report gunshots to police. Police don’t have to wait for citizens’ reports to find trouble, and residents who hear shots don’t have to wonder if police know about them.

Camden officials, who say the system allows police respond quickly to gunfire incidents, said it helped them reduce shootings in the city last year by 46 percent.

Philadelphia City Council president Darrell Clarke has said he’d like to bring ShotSpotter to Philly.

Clarke is hardly alone; cities including Boston, Washington, New Haven and New York now employ ShotSpotter, which uses data from multiple mics to calculate and report the precise location of a given shot.

But the system is not without controversy — or cost. Some cities have complained that it can confuse truck backfires and other loud noises with gunshots; one study in Newark found that three-quarters of ShotSpotter reports were false alarms.

In Trenton, two out of three reports were false alarms, and the city recently declined to revive the program after experimenting with it back in 2012. “The technology didn’t work when we had it before, and I don’t think it’s going to work now,” former Mayor George Muschal said last summer.

Company officials say those sorts of kinks have been worked out. But other issues are sparked by the effectiveness of the technology. ShotSpotter microphones can be sensitive enough to pick up voices on the street — the company insists that a normal, low-volume conversation has never been recorded, but louder exchanges have been captured by the mics and even used in court, raising questions about privacy rights and the admissibility of evidence.

Finally, like body cameras, ShotSpotter technology comes with a price tag both for hardware and for ongoing operational support from the manufacturer.

Such concerns notwithstanding, Kelvyn Anderson, director of Philadelphia’s Police Advisory Commission, said that ShotSpotter could be a useful addition to the law-enforcement toolbox — but only if used properly and carefully. It could provide clear and consistent data about where and when gun violence occurs, he said. And it could remove the burden of reporting shots from citizens, giving them confidence that anything they might hear through their windows will also register at police headquarters.

And if citizens start to see faster responses from police, that in turn might encourage better relations between communities and law enforcement, Anderson said.

“I think folks can be cynical about reporting things sometimes, particularly if they don’t get a response,” said Anderson. “So to the extent that police can take action based on what technology’s showing them, and show results, perhaps that will encourage people to report more.”

Still, before the city starts hanging out microphones, it should work out some ground rules first, Anderson said.

“As these technologies are being rolled out, we need to have a very public conversation about what the rules are, how it’s employed, what the policies and procedures for its use are,” Anderson said. “Those types of conversations are what will provide some accountability and assurance to the public.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.