Building art out of bricks in Princeton

Ceramic art has come a long way since Peter Voulkos crossed the line from functional craft to art form with his abstract shapes in the 1950s. One of today’s leading ceramic artists, Edmund de Waal, creates installations of hundreds of impeccably made cylindrical porcelain vessels in pastel shades of celadon or white.

Adam Welch: Bricks, on view at the Anne Reid ’72 Gallery at Princeton Day School through Dec. 19, explores how the brick characterizes postmodern appropriation, marrying concept and form.

“A large body of my work focuses on the brick as a shape and a concept, involving an intellectual investigation oriented toward art theory and ceramic history,” writes the artist.

Welch began his obsession with brick when he moved from Arizona to Richmond, Va., to earn his MFA in ceramics at Virginia Commonwealth University. Before then, “I was just making making making,” he said from his office at Greenwich House Pottery in New York, where he has been director since 2011. “In Richmond my focus shifted as a result of my surroundings. I went from expressionist to minimal, paring down superfluous actions.”

Brick was the object that could best fulfill that. “It’s part of the continuation of the modernist formalist notion of the essence of things,” said Welch, who is also a lecturer in the Visual Arts Program at Princeton University. “There is no more singular primary object, pared down, than the brick, and it fulfills so many functions in daily life.” That was Welch’s aha moment.

He began by making large block forms and solid walls. Bricks worked their way into his daily activities. “I started knowing nothing about bricks and had to research their history, function and manufacture.”

Clay or baked mud bricks were first used in the Middle East before 7500 BC, and bricks were first fired in China about 3,000 years ago. With the industrial revolution and the rise of factory buildings in England red brick became the building material of choice – it was faster and more economical than stone. The transition from hand-made brick to mass-produced brick happened in the first half of the 19th century.

Welch was interested in bonding, the patterns of stacking brick. His bricks were individually handmade but made to look uniform. Then he became interested in making them look more handmade, letting the handmade quality express itself. Stamping the brick is important in documentation, he says. Traditionally brick would be stamped with the name of the manufacturer, but Welch uses initials to describe how the brick is made. A brick stamped DP Welch is dry pressed, and a brick stamped HM Welch is handmade.

“Stamping identified the maker, but functions as a recessed area to encourage bonding between mortar and surface of brick,” said Welch. “There’s a connection between where I’m marking my work, sprawling big identification, and relating back to the history of brick making.”

Welch has been making bricks for 10 years. “I find there are limitless options and variables and ways you can manipulate the brick,” he said. “I continue to discover new things, and this show represents the culmination – putting the brick through a series of scientific tests to get to know the brick.”

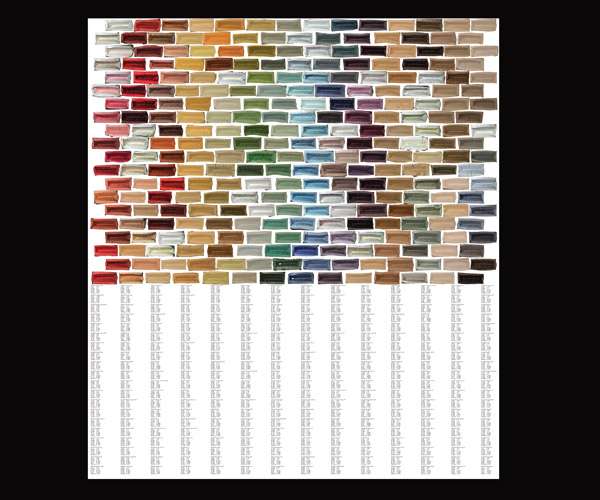

He took the brick to a testing facility and had it tested for porosity, tensile and compression strength. Next Welch put it through a series of photo doctoring, using different filters to “express the brick potential.” In one series he took a single brick and exposed it to 280 colors from Martha Stewart paint samples, painting one each color, and displayed these on the floor in the order of paint swatches at a hardware store, then photographed each one, lined up in a row, and sourced the color to the Home Depot website. “I pulled each one and put it into the same order so you can see the digital reality and the other reality – the actual brick – and the photographed reality, digitally reprinted.”

These three variations on perspective show the way we see the world now, the digitally reproduced reality and the completely computer-based reality. “I particularly liked Martha’s colors,” Welch added. He seemed to recall reading scholarly articles about ceramics written by Stewart early in her career, but then couldn’t be certain if he was just having a “weird dream.”

“There’s a larger connection related to her own professional trajectory,” said Welch. “The way she used the language to identify the colors – blueberry, schoolhouse red, cornbread – I was struck by the way she categorized them. She was eliminating the risk of having to decide. You can use any of these colors – you would know what color would work for the trim with a wall. I quite liked how she was simplifying the process for people who don’t have ability to make pairings. (In my own work) I was being critical but also appreciative.”

The exhibit includes a 40-minute video of the bricks slowly fading from one color to another. “The colors are very close, it’s subtle,” he said. “It’s like a digital flip book.”

Not surprisingly, Welch has been fascinated with the practice of “bricking up” – filling in windows of old buildings with brick. “Most of the bricks don’t match,” he said. “They come from different manufacturers.” So he became interested in re-creating these windows with his own glazed brick. He started to make digital mockups for a public art project. “That led to the idea of doing more and more investigating with brick in a way I couldn’t with the actual object. The original object is important to manipulate and take it to a level to further express what can’t be done in physical world.”

One of the works in the show, a digital print with 93 images of one brick over another, merged together, is based on the work of statistician and eugenicist Francis Galton, who created composite photographic portraits, hoping to create types that would help with medical diagnoses or identification of criminals.”

Based on this disproven concept, Welch has merged together individual bricks to give the essential characteristics of the brick itself. “It connects it all back to this idea, the modernist notion of unified theory. Paring down to the essential characteristics, getting rid of the periphery to find the core.”

__________________________________________________________

The Artful Blogger is written by Ilene Dube and offers a look inside the art world of the greater Princeton area. Ilene Dube is an award-winning arts writer and editor, as well as an artist, curator and activist for the arts.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.