Several birds named after Philadelphians will be renamed as part of an effort to stop honoring enslavers and racists

The American Ornithological Society will remove people’s names from birds. Many of those birds are now named after prominent Philadelphia scientists.

From Philly and the Pa. suburbs to South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

For more than two centuries, American ornithologists have been naming birds after people. The first two species to have honorific American names were given in 1811: Lewis’ woodpecker and Clark’s crow, now called Clark’s nutcracker.

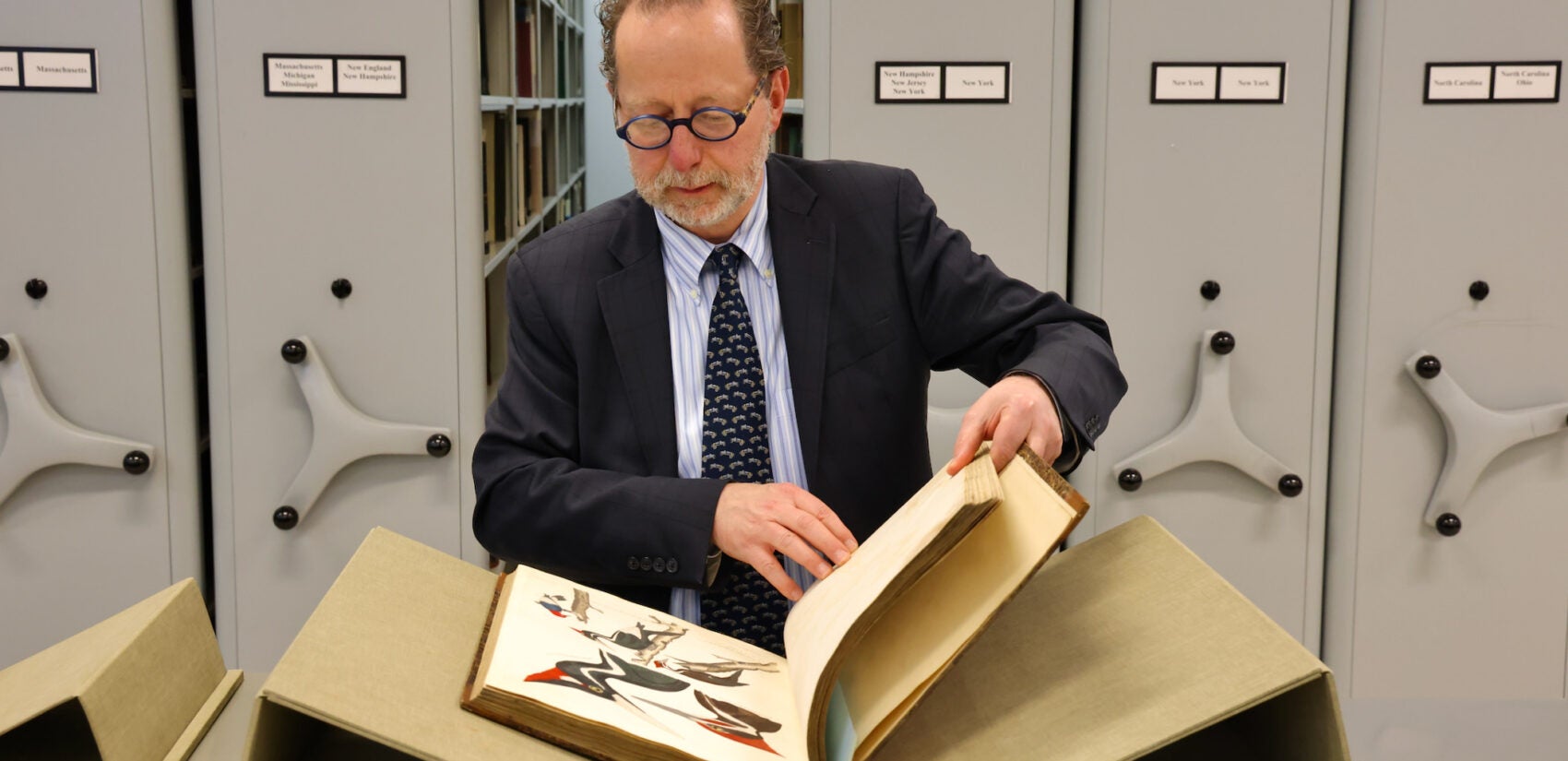

“They were collected by Lewis and Clark on their famous expedition across the country from 1804 to 1806,” said Robert Peck, senior fellow and curator of art and artifacts at the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University.

He showed off two taxidermied specimens of the Lewis and Clark birds in the Academy’s archive, which has the preserved bodies of about 8,000 species of birds. Peck opened an original copy of Alexander Wilson’s “American Ornithology” (1808) to the page where the birds were first illustrated and identified.

“These are iconic birds from the West that nobody here on the East Coast had ever seen before,” he said.

The names of Lewis and Clark will soon be stripped from the birds, along with every other bird name bestowed in honor of a person. The American Ornithological Society announced its ongoing bird renaming project last November, an effort expected to be carried out in phases over a few years.

Because some common bird names were given in honor of men whose lives did not uphold certain moral standards — primarily slave ownership — the AOS has decided on a blanket policy to remove everyone’s name regardless of the life they led, and develop new names based on the characteristics of the birds.

“There has been historic bias in how birds are named,” wrote Judith Scarl, the AOS executive director and CEO, in a statement. “Exclusionary naming conventions developed in the 1800s, clouded by racism and misogyny, don’t work for us today.”

Philadelphia: The birthplace of American ornithology

Many of those names common to birders, although not to the average person, honor prominent Philadelphia scientists.

Philadelphia can make a claim to be the birthplace of American ornithology. Wilson left Scotland in 1794 dogged by libel lawsuits due to his satirical poetry about weaving mill bosses. He came to Philadelphia and studied thousands of bird specimens collected by Charles Willson Peale at Independence Hall.

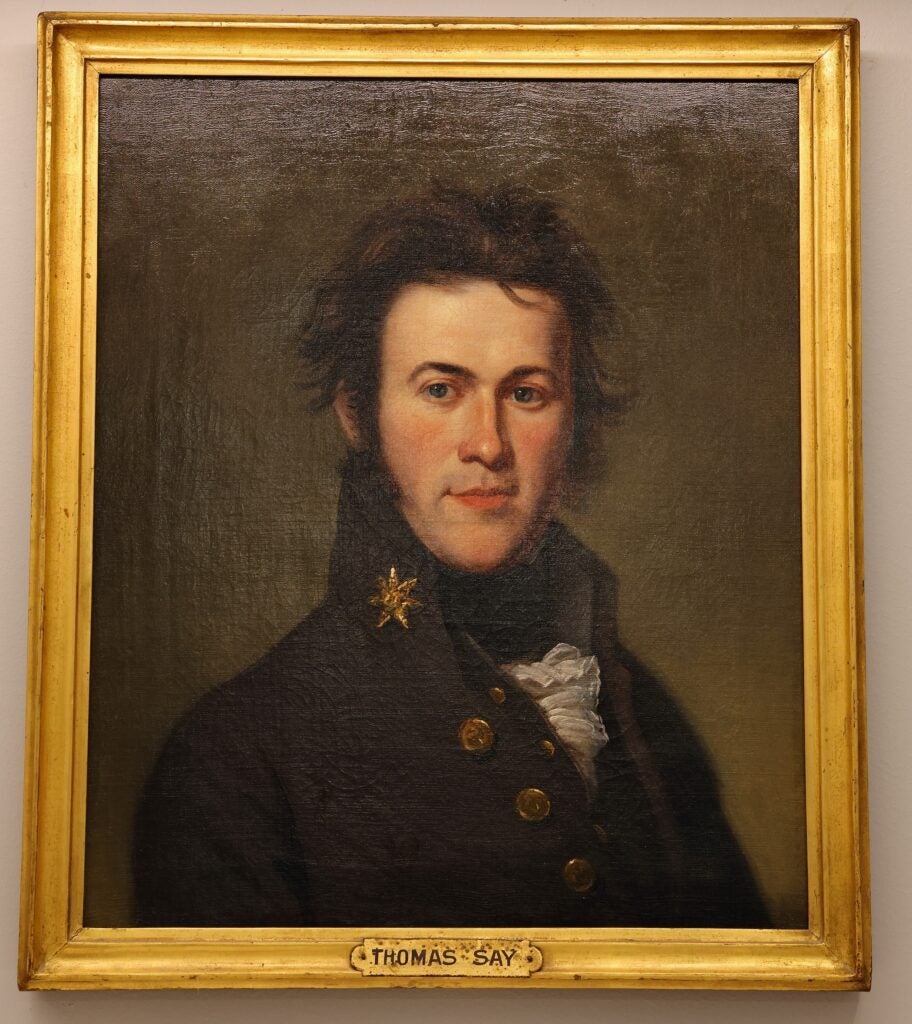

Wilson began publishing his multivolume set “American Ornithology” in 1808, cementing himself as the father of American ornithology. He was part of a formidable network of early scientists who founded the Academy of Natural Science, including luminaries like William Bartram, Titian Peale, Thomas Say, James Audubon, John Cassin and John Kirk Townsend.

They all have birds named after them, such as Wilson’s snipe, Bartram’s sandpiper (Bartramia longicauda, or upland sandpiper), Peale’s falcon, Audubon’s oriole, Cassin’s finch, Say’s phoebe and Townsend’s warbler.

“So many of the first descriptions of birds came out of Philadelphia. That’s why so many of these birds are named for Philadelphians,” Peck said at the Academy. “It’s understandable that people find associating human names with birds unnecessary. They certainly don’t help us understand the birds any better. They do sometimes help us understand history.”

Controversies around naming plants and animals after people have been swirling since people started naming flora and fauna. A curator at the Delaware Museum of Nature and Science, Matthew Halley, found a 1799 unpublished writing by Peale urging scientists to get rid of the “unmeaning custom.”

“I mean that of naming subjects of nature, after persons, who have plumed themselves with those childish ideas of their being the first discoverers of such or such things,” Peale wrote.

His objections were largely unheeded. The ornithologist Robert Ridgway later named Peale’s falcon after Peale’s son, Titian.

The early days of natural science was literally a wild frontier. In the 18th and 19th centuries men scrambled to all regions of the globe propelled by the promise of being the first to describe and name every animal, vegetable and mineral on earth. The frenzy to seek and identify as many species as possible was sometimes more driven by ego than rigor.

“For some it was a religious motive. They thought that these were God’s creations and the more we knew about them the more we would admire God,” Peck said. “For others it was a much more clinical approach. Almost like stamp collecting. You could check the box. You had them all.”

Titian Peale and Thomas Say, for example, were hired to join an expedition to the western part of the continent to record species. In anticipation of possible conflict with British and native people in those territories, they traveled with a military outfit. The naturalists were issued their own soldier uniforms to make the unit appear more formidable than it actually was.

Before the expedition, Charles Willson Peale painted portraits of both Titian and Say so that he would have a visual record if they died. If they made it back alive he would have portraits of the victorious heroes. They lived.

On the other hand, John Cassin, considered the nation’s preeminent bird expert in the 1840s, was less adventurous. The newly minted Smithsonian Institute asked him to be its official taxonomist to describe specimens brought back from western expeditions, a territory he never visited.

Cassin, who by most accounts led a quiet and dutiful life dedicated to birds, died from his passion. He treated bird specimens with arsenic — the standard chemical preservative of the time — which over time poisoned him. His archived letters suggest he knew his work would ultimately kill him.

There are five birds named after Cassin: Cassin’s auklet, Cassin’s kingbird, Cassin’s vireo, Cassin’s sparrow and Cassin’s finch. After the American Ornithological Society removes Cassin’s name from the birds, he will still be remembered on the cover of the Delaware Valley Ornithological Society’s newsletter, “The Cassinia.”

Documenting scientific discovery and racist science

Some of those early scientists behaved in ways shunned today. Audubon owned slaves. John Bartram bought slaves for his son William to use on his Florida plantation, according to a posting by Bartram’s Garden.

William sold at least one of those enslaved people, a woman named Jenny in 1772, to raise cash to fund a species-hunting expedition. The original bill of sale is now on view at the American Philosophical Society’s new exhibition “Sketching Splendor: American Natural History 1750–1850.”

Later in life William Bartram held abolitionists ideals. In 1790 he included an anti-slavery treatise in his published plant catalog for his family’s nursery business.

ASP curator Anna Majeski said the exhibition was designed, in part, as a response to the AOS renaming project.

“It’s very tempting to just celebrate these people’s scientific contributions, and they did make scientific contributions,” Majeski said. “But you have to engage with both sides of American natural history. It’s a very complicated practice, which is really related to colonization and plantation slavery.”

An APS member in the 1930s named John Kirk Townsend went on a westward expedition to send back plant and animal specimens. He also robbed the graves of Native Americans and sent skulls to Dr. Samuel Morton, who was then assembling a collection of crania in an attempt to biologically prove racial superiority.

Now discredited as racist science, the controversial Morton Crania Collection is at the Penn Museum, which is working to repatriate its contents.

Titian Peale and Audubon are also known to have robbed human remains from the graves of Native Americans, a fact pointed out in the exhibition wall text at the Philosophical Society.

In the archive of the Philosophical Society is a letter by Townsend describing in detail his grave-robbing activities, which Majeski said is too disturbing to put on public display, but it has been posted online. Two birds, a warbler and a solitaire are named after Townsend.

Renaming the renamed birds

Naming birds after people was part and parcel to a colonialist drive for dominion. As “Sketching Splendor” shows, Native American people already had names for the flora and fauna of the American continent. Those 18th and 19th century scientists took it upon themselves to rename birds after themselves.

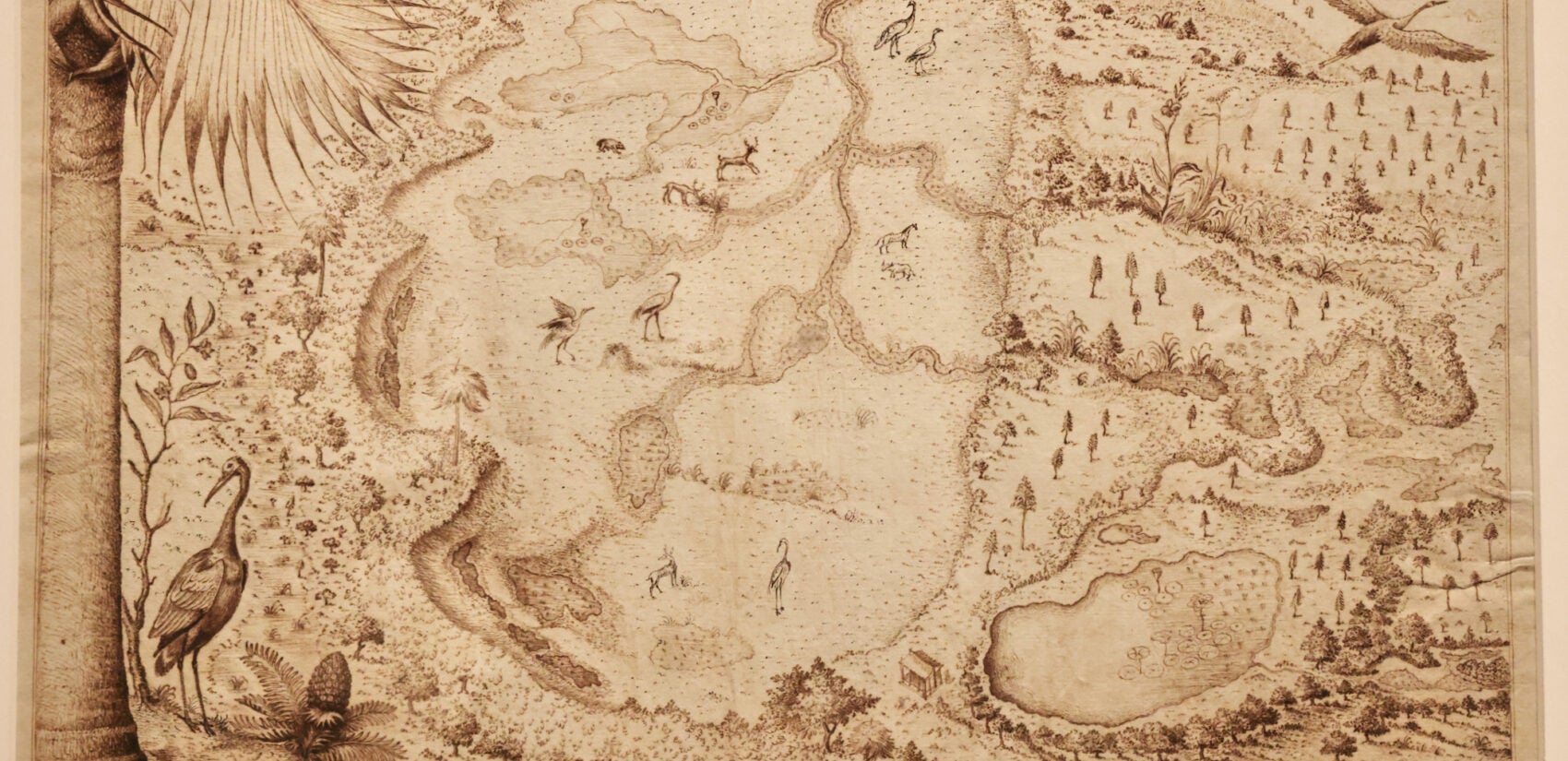

Majeski said the early naturalists were inextricably tangled in both their awe of the New World and its potential to be exploited for its commodities. William Bartram, for example, explored parts of the Florida Savanna that were occupied by the native Seminole people.

“In the travels he is really, on the one hand, this champion of Native American rights and sovereignty,” she said. “A few months later when he goes to Savanna a second time, he talks about how this would be a wonderful site for a European-style settlement and could house hundreds of thousands of people. It’s difficult to understand how in his mind that kind of settlement could equate with Seminole sovereignty. He’s a deeply unresolved figure.”

The work of ornithology consumed the lives of those who entered it. People were known to perish falling out of trees and off cliffs pursuing an elusive species.

Alexander Wilson died in 1813 exhausted and impoverished, not living to see the completion of his monumental “American Ornithology” in all its nine volumes. The later volumes were completed posthumously by his devoted disciple, George Ord.

Like Peale, Wilson was not a fan of naming birds after people, preferring more descriptive names. In his book he illustrated what he called a green black-capped flycatcher, a name describing the bird’s appearance and behavior. Only after his death the bird became known as Wilson’s warbler.

Natural history’s connection to colonization

A complete set of original “American Ornithology” is housed at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, in Philadelphia, where director David Brigham takes a personal interest. His history PhD was based on the 17th and 18th British naturalist Mark Catesby, who identified hundreds of plants and animals on the American continent.

“The work of colonization and the work of natural history are really side-by-side disciplines,” Brigham said. “They might not have expressed it that way, but the people who are subscribing to these books for their beautiful libraries were also involved in tea, plantations, quinine and other things coming out of the natural world and becoming valuable products.”

Many early naturalists believed the work of describing the New World was part of nation-building. Wilson once threw his hat into the patriotic ring by writing a possible national anthem and submitting it to a contest. Charles Willson Peale looked to animals for cues on forming a new country.

“He thought animal behavior was a natural model for human behavior,” Brigham said. “He was very clear about how the behavior of natural creatures could provide a model for a republic.”

Efforts to make birding more inclusive

The complicated history of racism and colonialism of early naturalists is one reason the Ornithological Society believes people may be turning away from birding. Jason Hall is on board with that. The founder of In Color Birding leads birdwatching outings in the Philadelphia area for people who may otherwise feel uncomfortable birding due to race, gender, disability or sexual orientation.

Hall has been watching the AOS debate its bird renaming project for years and has incorporated it into his walks.

“We don’t want our members falling into the volatility of anger and resentment, albeit understandable considering some of the racist history in some of these names,” he said. “We think it’s more productive to say, ‘If this is happening, what new names can we give it? How much fun can we have with this?’”

People have been turning to social media to make up alternative bird names under the hashtag #BirdNamesForBirds. Hall points to the Blackburnian warbler, one of the few birds named after a woman: Anna Blackburne, an 18th century British botanist.

“It’s got a bright orange throat. One of the coolest names people have come up with was ‘flame-throated warbler,’” Hall said. “But the female type does not have the same characteristics. It has led to the more interesting and diverse conversation around, ‘Why are we only naming these birds after the male type?’”

“It’s opening a place for really new and interesting conversations,” he said, “outside of just, ‘Let’s get rid of these racist names.’”

Saturdays just got more interesting.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.