Bayard Rustin, the hidden activist of ‘Selma’

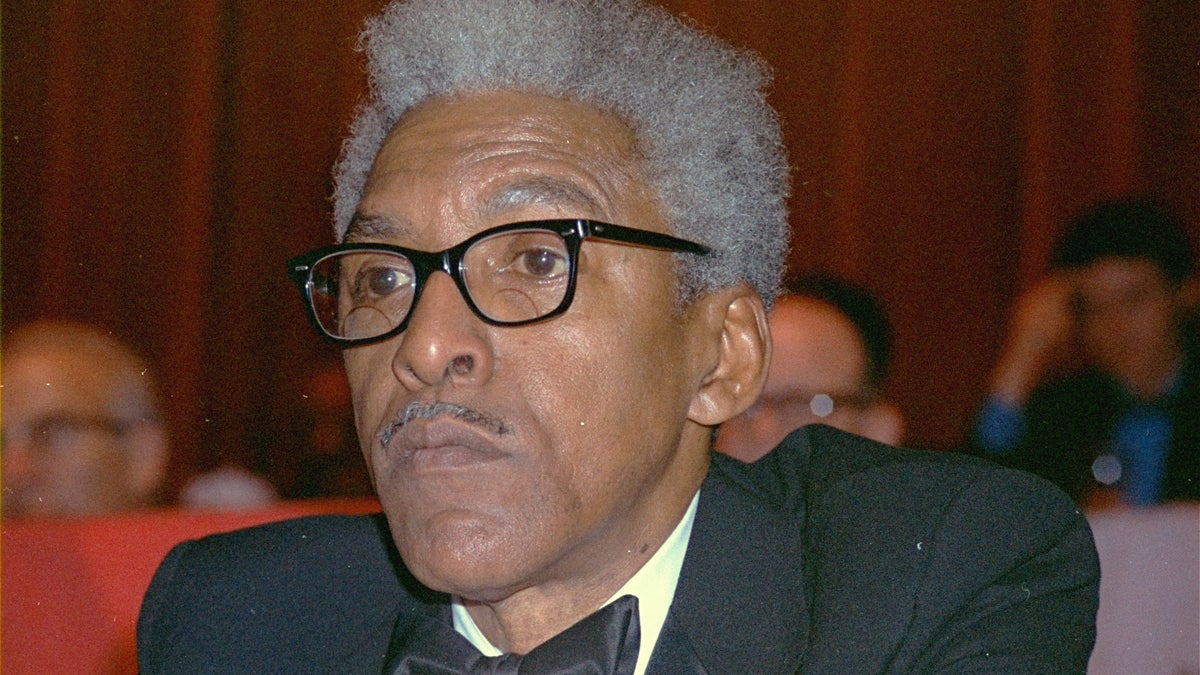

Civil rights leader Bayard Rustin is shown in New York in 1970. Months before Martin Luther King Jr. declared “I Have a Dream” to galvanize a crowd of thousands, Rustin was planning all the essential details to make the 1963 March on Washington a success. Rustin, who died in 1987, is sometimes forgotten in civil rights history. He had been an outcast. He was a Quaker, a pacifist who opposed the Vietnam war and had flirted with communism. And he was gay. (AP Photo/File)

Despite his monumental influence over America’s civil rights and LGBT rights movements, Bayard Rustin has yet to catch the attention of the nation’s mainstream film industry. He does not even get his due in ‘Selma.’

History can be divided into two narratives — the remembered, and the invisible.

In the Academy Award-nominated “Selma,” we see a monumental figure in history, Dr. Martin Luther King, taking on other major figures in a small Alabama town in the fight for equal voting rights.

For those of us born after the 1965 march from Selma to Montgomery, the movie does an excellent job of pointing these major figures out to us — President Lyndon B. Johnson, infamous FBI director J. Edgar Hoover, eventual Congressman Andrew Young and other leaders of Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), figures of authority in Alabama — except for one man: Bayard Rustin.

Rustin does not get directly identified to us in “Selma,” and for whatever reason, his influence on Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and his work behind the scenes barely receive screen time. While great pains were taken to identify the major players behind the Selma march, Rustin is the one pivotal player whose name is never spoken to him at any point during the film’s 127 minutes.

Bayard Rustin lends his name to two educational institutions, including a high school in West Chester, Pennsylvania. He is the subject of award-winning documentary “Brother Outsider,” and he is portrayed in the 1998 film “Out of the Past.” And beyond his diminished portrayal in “Selma,” his role in the planning and execution of key events in the Civil Rights Movement, and his influence on King, have either gone unrecognized by or been blatantly omitted from cinema.

His name receives nowhere near the same attention as King. A search for “Bayard Rustin” on IMDb.com yields barely a handful of results, but a the same website lists more than 20 biographical films or portrayals of King and several TV program characterizations (“Saturday Night Live,” “Drunk History”) and TV movies (“Eyes on the Prize,” “The Rosa Parks Story”).

Rustin’s own history may explain why.

An ‘angelic troublemaker’

Bayard Rustin was born in West Chester in 1912 and raised by his grandparents. His grandmother’s Quaker influence would prove powerful. It was Rustin who introduced the idea of non-violent action to King and members of SCLC, having already implemented many of Gandhi’s teachings on non-violent resistance during the course of his work with the Congress for Racial Equality (CORE), a pacifist organization, in 1942.

But Rustin was deemed a major risk to the movement, as he was openly gay at a time when many states had laws that criminalized homosexual behavior. As a result, he largely worked behind the scenes, managing the details of marches, boycotts, and strategies to attract greater media coverage of police brutality against peaceful protestors. The film “Selma” hints at this a bit, as it is Rustin who calls members of SCLC on the phone to let them know that footage of police brutality against Selma marchers has hit the airwaves.

His identity as a gay man was not the only issue for the other leaders of the Civil Rights Movement. In a 1987 interview, Rustin revealed that his time behind bars (he served three years as a conscientious objector, for refusing to enlist in the American war effort during World War II) and his membership as a young man with the Communist Party were major headaches for civil rights leaders. These concerns nearly got Rustin barred from participating in the planning of the historic March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in 1963.

In the end, however, King gave his trusted advisor his vote of confidence, and Rustin became the director of the march.

Rustin remained an activist until his death in 1987. He fought for human rights around the world, from El Salvador to South Africa. He advocated for the passage of anti-discrimination laws for gay and lesbian Americans in the 1970s and ’80s and put the AIDS crisis on the NAACP’s radar. During his lifetime, he said, “We need, in every community, a group of angelic troublemakers.”

A tough sell in Hollywood

Despite his monumental influence over two major movements in American history, Bayard Rustin has yet to catch the attention of the nation’s mainstream film industry. Movies glorifying the efforts of activists fighting the good fight have been popular draws for moviegoers for decades, and “Selma” is one of two films from the tail end of 2014 receiving high praise and awards recognition.

“Pride,” a historical drama about gay activists who raised money for miners during the 1984 strikes in Britain, received accolades at the Cannes Film Festival in 2014 and was nominated for Best Picture for a Musical or Comedy at the Golden Globes this month.

Walter Naegle, Bayard Rustin’s partner during the last 10 years of his life, believes that Hollywood’s slow acceptance is one explanation for the lack of Rustin-centered films.

“[H]e was gay, and the popular culture is just warming up to the idea of gay lead characters and, unfortunately, they are usually somewhat stereotypical,” he said.

Slow acceptance of gay men aside, Hollywood seems to have trouble showcasing complex, multidimensional characters of any kind. The popular narrative likes its heroes painted in a single brush.

The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences is known for favoring one-dimensional representations of historical figures in its nominations. Denzel Washington has received Academy Award nods for his portrayal of real-life individuals on many occasions, from apartheid activist Stephen Biko in “Cry Freedom” to wrongfully convicted American boxer Rubin “Hurricane” Carter in “The Hurricane.”

These characters, beautifully acted as they were, are shown to us merely as victims of white oppression. We are not given a peek into their human flaws, the characteristics that some Americans may find distasteful, or the work they accomplished outside of the causes that made them household names.

Our heroes are complex individuals. It’s a shame Hollywood insists on ignoring those complexities. As a result, a large portion of figures deserving of cinematic portrayal are eliminated from consideration, including Bayard Rustin.

Naegle, who co-wrote the young adult biography “Bayard Rustin: The Invisible Activist,” understands that his partner’s accomplishments may prevent him from becoming the focus of a Hollywood movie, but it’s those accomplishments that set him apart from the rest.

“The idea of a strong, gay, black man who was athletic in his youth, and an activist, intellectual, and political strategist as an adult may be difficult to condense into a single man. Yet that’s who Bayard was and that was what made him exceptional.”

—

CORRECTION: A previous version of this essay stated that Bayard Rustin was raised by Quaker parents. He was raised by his grandparents. His grandmother was a Quaker, and his grandfather belonged to the African Methodist Episcopal Church.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.