At an Elkins Park synagogue, celebrating 60 years in one of Frank Lloyd Wright’s last buildings

The Beth Shalom synagogue outside Philadelphia celebrates 60 years in its unusual buildings by commissioning artwork by David Hartt.

-

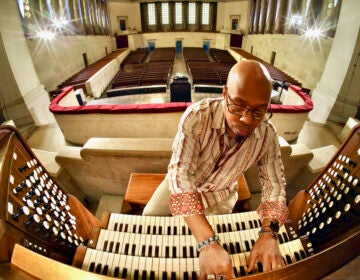

Visual artist David Hartt has installed an exhibit at Beth Sholom Synagogue in Elkins Park, designed in the 1950s by architect Frank Lloyd Wright. The exhibit includes tropical plants along with videos, tapestries, and music. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

-

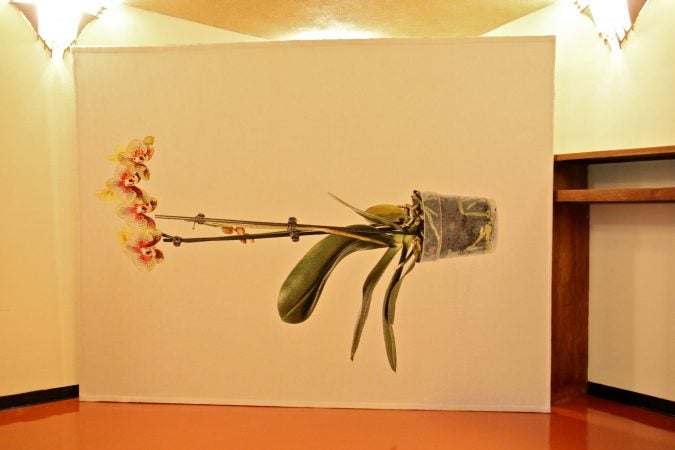

Orchids in the temple are placed under persistent leaks in the towering translucent roof, designed by Frank Lloyd Wright. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

-

Orchids in the temple are placed under persistent leaks in the towering translucent roof, designed by Frank Lloyd Wright. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

-

David Hartt has placed tropical plants in existing containers usually filled with plastic plants. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

-

Visual artist David Hartt has installed an exhibit at Beth Sholom Synagogue in Elkins Park, designed in the 1950s by architect Frank Lloyd Wright. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

-

Visual artist David Hartt has installed an exhibit at Beth Sholom Synagogue in Elkins Park, designed in the 1950s by architect Frank Lloyd Wright. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

-

Visual artist David Hartt has installed an exhibit at Beth Sholom Synagogue in Elkins Park, designed in the 1950s by architect Frank Lloyd Wright. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

-

Visual artist David Hartt has installed an exhibit at Beth Sholom Synagogue in Elkins Park, designed in the 1950s by architect Frank Lloyd Wright. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

-

Visual artist David Hartt has installed an exhibit at Beth Sholom Synagogue in Elkins Park, designed in the 1950s by architect Frank Lloyd Wright. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

-

Beth Sholom Synagogue in Elkins Park is the only synagogue designed by architect Frank Lloyd Wright. The building was completed in 1959. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

Next week, one of the last buildings designed by Frank Lloyd Wright turns 60 years old. The Beth Sholom synagogue in Elkins Park was completed in 1959, just a few months after the architect died.

It is one of Wright’s more unusual designs, with a soaring, angular dome resembling something between a glass mountain and a spaceship.

On its 60th anniversary, the building is now part of an artist commission. David Hartt was asked by the caretakers of the building, the Beth Sholom Synagogue Preservation Association, to create something that might drive interest to the building outside of its regular visitation by Jewish congregants and architecture buffs.

“The Histories (Le Mancenillier)” may seem very subtle to some visitors. The centerpiece of the buildings – the worship space underneath the dramatic glass dome – has been arranged with dozens of potted orchids, serenaded by piano music coming from speakers placed on the perimeter of the room.

Sharp observers may also notice new plants in the planters. When Frank Lloyd Wright designed them, he determined they should be filled with plastic plants. For the last 60 years, the fake green plants in the synagogue have been according to the architect’s wishes. But for “The Histories,” they’ve been replaced by colorful tropical varieties. All of those are real.

Between the live plants and classical piano music, the space has the feel of a day spa. Visitors may miss the deeper meaning if they don’t know the back story.

“The music that you’re hearing is not just any music,” said Herb Sachs, president of the preservation association. “It was recorded by an Ethiopian pianist that we brought in specifically for the recordings. The composer is Gottschalk, and he has his own history.”

Louis Moreau Gottschalk was a mixed-race composer from New Orleans who was one of the most well-known pianists of the mid-19th century. Many of his compositions are lost today but one of them, “Le Mancenillier,” is the parenthetical title of the installation.

The piece takes the French name of the manchineel tree, a species native to America that is considered one of the most toxic trees in the world. All parts of the plant are poisonous. If you were to stand underneath one during a rainstorm, your skin would blister.

“Hartt considers the plant to be anti-colonial in that an arrow dipped in the sap of the manchineel is said to have killed Ponce de Leon, the conquistador who led the first European expedition o what is now Florida,” wrote the curator, Cole Akers, in the short program for the exhibition.

The program is an essential part of the experience. There is little in the display to cue a visitor as to what Hartt is trying to communicate in “The Histories.” A deep knowledge of both art-historical figures is needed. A second central figure for Hartt is Martin Johnson Heade, a 19th-century painter of salt marshes and wild orchids.

Inspired by Heade, Hartt created large woven tapestries of tree canopies and orchids and installed them in small side rooms off the lobby of the synagogue.

Knowledge of the history of Philadelphia and urban development is useful, too. Hartt is making reference, obliquely, to the twin movements of African-American and Jewish population around the city. The Beth Sholom congregation used to be located in the Logan neighborhood but decided to move out of the city mid-century.

Logan became a predominately African-American neighborhood. Beth Sholom’s old synagogue on North Broad Street was acquired and occupied by the Beloved St. John Evangelistic church.

“Rather than focus on the architecture, David decided to focus on the broader history of the congregation and the way it related to urban development in Philadelphia,” Akers said.

Hartt did, however, make playful reference to the building in which he installed work. The potted orchids are arranged in a seemingly random pattern around the seating of the synagogue.

But nothing is random, here. As with many Frank Lloyd Wright-designed buildings, the roof leaks. Because of the way the dome was designed – with glass panels in a steel frame – preventing leaks is next to impossible. In its 60 years in the building, they have learned to live with leaks by placing buckets on the floor during rainstorms.

The orchids are there to replace the buckets. They catch raindrops in a way they might if under a rainforest canopy.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.