As COVID-19 creeps closer to Philly, city officials urge precaution

City health officials outlined a plan for identifying patients with symptoms and said as the situation changes, so will the response.

City Health Commissioner Thomas Farley provides an update on COVID-19. on March 6, 2020 (Bastiaan Slabbers for WHYY)

Updated 10:40 a.m. March 7

City officials are preparing for COVID-19 to arrive in Philadelphia, and assuming it does, they say they are ready to contain it.

They’re not yet taking severe measures such as travel restrictions or school closures, as have been seen in other cities where the virus has already hit.

“We regularly work with our hospital and health care communities to prepare for this type of situation, so we’re confident that if we get a case, our response will be ready and appropriate,” Mayor Jim Kenney said.

As of Friday evening, there were no confirmed cases of COVID-19 in Philadelphia, but there are two in Pennsylvania, including neighboring Delaware County, and three in New Jersey.

City health commissioner Thomas Farley outlined a plan for identifying patients with symptoms, testing them and isolating them for 14 days.

“If we can execute on this strategy, we can contain this virus,” he said.

Farley said if cases begin to spread, the city might consider more drastic measures such as canceling public gatherings and trying to limit crowds. For now, though, SEPTA is up and running, schools are open and Philadelphia International Airport is operating as normal.

Per CDC guidelines, people should be tested who have respiratory illness symptoms, particularly a rough cough and a fever, and have either traveled to an area where COVID-19 is present or has had contact with someone who has. Pennsylvania has the capacity to test at one state lab and two commercial laboratories: LabCorps and Quest. Commissioner Farley indicated that patients who feel ill but don’t meet these criteria should not be tested, so as not to overwhelm the state’s testing capacity.

Friday, the Pennsylvania Health Department reported its first two presumptive positive cases of COVID-19, one in Delaware County, and one in Wayne County. One patient had recently traveled to another state where the disease is present, and one had been to another country. Both are currently at home in isolation.

New Jersey announced its third positive case of coronavirus Friday — the first in South Jersey.

Officials say the Camden County man in his 60s is currently hospitalized in stable condition. Two other patients are hospitalized in Bergen County, in North Jersey.

The state sent specimens from all three patients to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to confirm the test results.

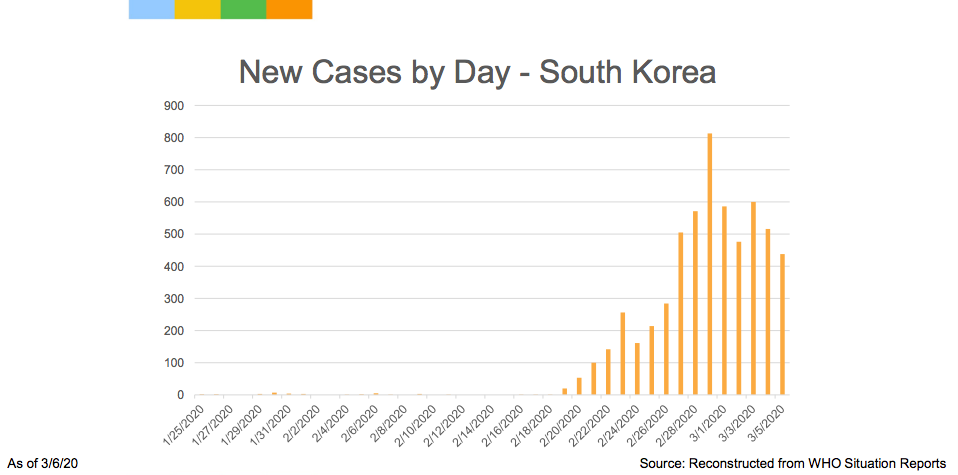

In other cities worldwide that have instituted containment strategies similar to city proposals, the disease has still spread. But in China and South Korea, the two countries that have seen the most cases, the incident rate appears to have peaked and is now declining. Farley said despite the high number of illnesses, he takes that as an indication that containment strategies did in fact work.

“This suggests to me the systems that they put in place are working, and if we follow those same systems, we will ultimately have success as well,” Farley said. “That’s not saying we won’t have an increase initially, I would expect we probably would. But that does say that over time we ought to have success.”

Health department spokesperson Jim Garrow explained that during an epidemic, the goal is to squash the bell curve of incident rates down so that it’s flatter. That might mean the same total number of people get sick overall, but fewer are ill at any given time. That way, there is less pressure on the health care system, and less overall interruption to daily life: less work missed, fewer school closures, fewer events canceled. The implication here is that the greatest risk of a disease spreading at this scale is not necessarily the health outcomes.

“Most of the cases are mild and self resolve,” Garrow said. “The idea is to reduce the amount of disruption that a novel disease like this will have on society.”

Avoiding those disruptions is important from an equity perspective, said Alison Buttenheim, who researches how people respond to infectious diseases for Penn’s Center for Health Incentives and Behavioral Economics.

Research has shown that three days of school closures amount to about 400,000 meals that Philly kids aren’t guaranteed. Plus, if schools are canceled, arranging for child care can be a huge burden.

To that end, Buttenheim recommends an abundance of caution when it comes to individual behavior to help prevent the virus’s spread. Even if you might not be at high risk of picking up the virus, she said your activities might strain the system, making prevention and treatment efforts harder for those more susceptible.

“If you can not go, don’t go,” Buttenheim said of even domestic travel plans. “If you can not contribute to overcrowding and stressing and taxing the health care system, do that.”

In a sense, she said, prevention measures like these can seem frustrating because they have very little visible payoff.

But there’s a clear upside.

“If we do everything right,” she said, “it will look like nothing happened.”

—

This article has been updated to clarify the number of meals school closures could affect.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.

![CoronavirusPandemic_1024x512[1]](https://whyy.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/CoronavirusPandemic_1024x5121-300x150.jpg)