Artists express what Philadelphia’s future looks like to them

ListenThis weekend the Philadelphia Museum of Art opens an exhibition that attempts to envision a future of the city from as many perspectives as possible.

“Philadelphia Assembled” has been three years in the making, involving 150 artists and dozens of public engagement projects.

A Dutch artist named Jeanne van Heeswijk instigated “Philadelphia Assembled,” but she is the first one to tell you it’s not really her project. After talking with hundreds of people around the city at the invitation of the Art Museum, she created a set of questions to be answered about land usage, gentrification, criminal justice, economic sovereignty, and personal safety.

Those issues are organized into categories: Sovereignty, Reconstructions, Sanctuary, Futures, and Movement. She calls them “atmospheres.”

“They are more than themes” said van Heeswijk. “They are porous. They are clouds. They are different understandings than a theme.”

She then assembled a team of 150 artists to investigate those atmospheres. That team was set loose throughout the city to engage residents in social experiments toward a vision of the future of Philadelphia.

“Quite often, images of the future are projected to us, like, this is how a successful or thriving future looks like,” said Van Heeswijk. “I am interested in what an inclusive future looks like. What images does it hold? What kind of stories does it hold?”

Philadelphia Assembled is challenging to both visitors to the museum, and to the museum itself. Van Heeswijk does not create artworks, but fosters relationships among people that may or may not result in something that can hang on a wall. As it happens, enough physical material came out of the civic engagement events to fill all of the galleries in the Museum’s Perelman Building.

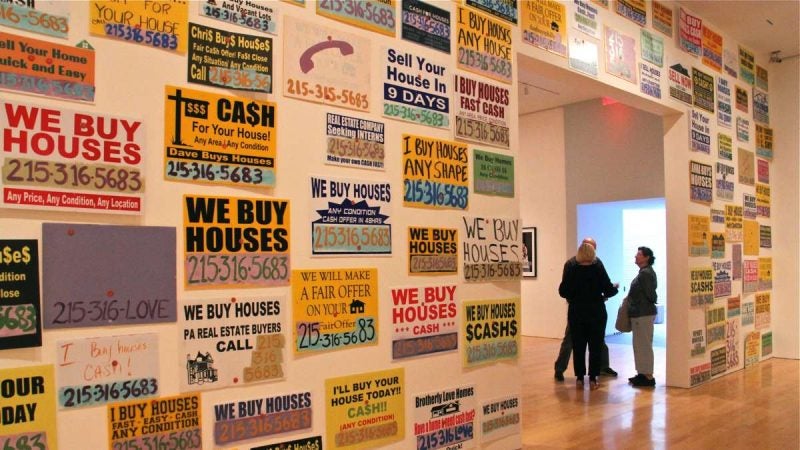

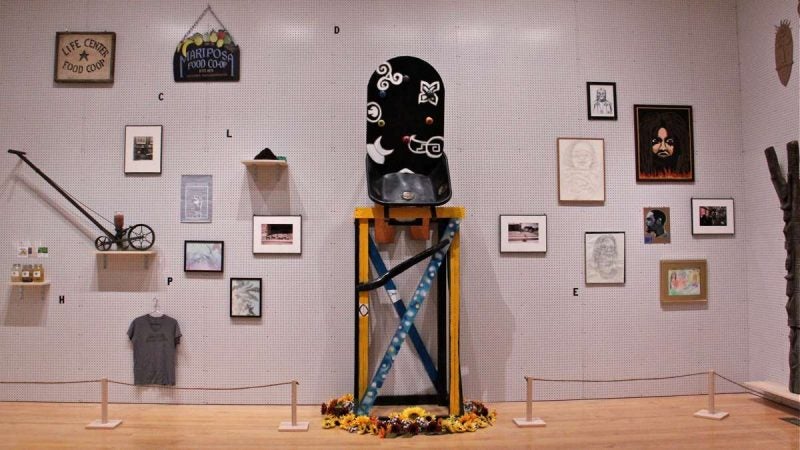

It’s a kitchen sink of artwork from a variety of hands: a birthing chair made from an old wheelbarrow, photographs of women whose husbands are incarcerated, mind maps of Philadelphia delineating landmarks that are significant to differnet communities, a geodesic dome furnished with carpets and pillows creating an inclusive sanctuary city, a collection of real estate bandit signs, hand-made birdhouses, hand-painted mirror lockers, African masks, a full-sized, partially framed first floor of a typical Philly rowhome.

For the museum, this is an experiment in “radical inclusion” in accordance with an administrative strategic plan to be more engaging with the public outside its walls. The exhibition gives up some curatorial focus to embrace a widely democratic array of objects and stories, cobbled together as vision of what the city is now and what it could become.

The organizational structure Van Heeswijk hatched even took over the operation of the museum’s gift shop and restaurant. The café in the Perelman building’s — normally contracted to the Starr Restaurants — will be temporarily operated by a collective of culinary artists from Philadelphia Assembled.

The museum was forced to be flexible to accommodate a set of artists who have not always been fans of the Museum.

“There are ways that systems fail us every day,” said assistant curator Amanda Sroka. “The museum is a hierarchy and a place that some members of the community across Philadelphia feel they don’t have access to. So many people have come through this gallery and said to me, I see myself in the show in ways I’ve never seen — me, my face, my story.”

“Philadelphia Assembled” will be on display until December.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.