Army: Exhumed remains don’t match 19th century Indian child

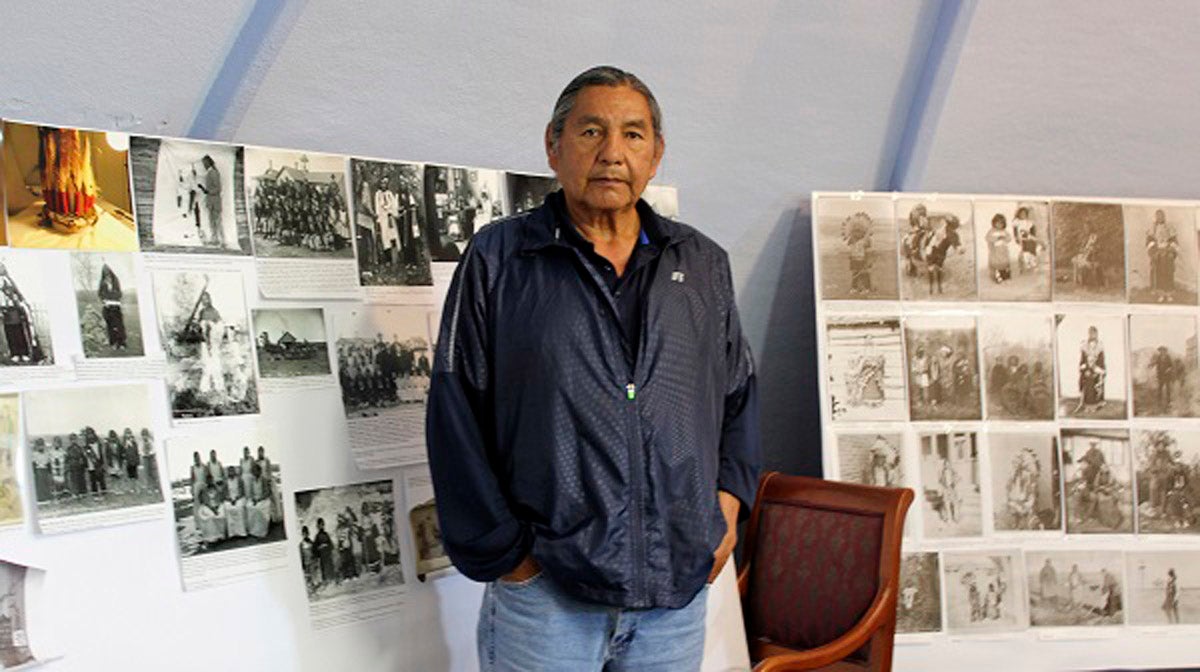

Russell Eagle Bear, the historic preservation officer for the Rosebud Sioux Tribe, looks at photos and maps in his office in Rosebud, S.D., of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania. Eagle Bear led a meeting last year between leaders of several tribes, including the Rosebud Sioux Tribe, and representatives from the U.S. Army to address the possibility of repatriating the remains of at least 10 Native American children who died away from their homes while being forced to attend the school more than a century ago. (Regina Garcia Cano/AP Photo)

Remains unearthed at a Pennsylvania Army base don’t match the Native American child thought to have been buried there after dying at the government-run Carlisle Indian Industrial School in the 19th century, authorities said Friday.

The U.S. Army said Friday the grave thought to contain 10-year-old Little Plume, also called Hayes Vanderbilt Friday, doesn’t match his age, and in fact contains two sets of unidentified remains.

The remains of 15-year-old Little Chief, also known as Dickens Nor, and 14-year-old Horse, also called Horace Washington, do match and will be returned to a Northern Arapaho delegation on Monday. They’ll be reburied in Wyoming’s Wind River Reservation.

The grave with Little Plume’s headstone contains remains from a teenage male and another person of undetermined age or sex. They will be reinterred at the site.

The government-run Carlisle Indian Industrial School, founded by an Army officer, took drastic steps to separate Native American students from their culture, including cutting their braids, dressing them in military-style uniforms and punishing them for speaking their native languages. They were forced to adopt European names.

More than 10,000 Native American children were taught there and endured harsh conditions that sometimes led to death from such diseases as tuberculosis.

The exhumations began early Tuesday at the post cemetery on the grounds of the Carlisle Barracks, which today houses the U.S. Army War College.

Seventeen members of the Northern Arapaho tribe, including tribal elders and young people, came to Carlisle to take part in the process. In 2016, the tribe had formally requested the bodies be returned to them.

“The U.S. Army honored its promise to reunite Native American families with their children who died more than 100 years ago at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School,” Army National Military Cemeteries Executive Director Karen Durham-Aguilera said in a statement. “We are thankful to the Northern Arapaho families for their patience and collaboration during this process.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.