Is the American shopping mall dead? The Philadelphia area has seen its fair share disappear

Industry experts believe the mall is not extinct, but evolving. However, there is a difference between the institution and a beloved small town mall like Granite Run.

From Philly and the Pa. suburbs to South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

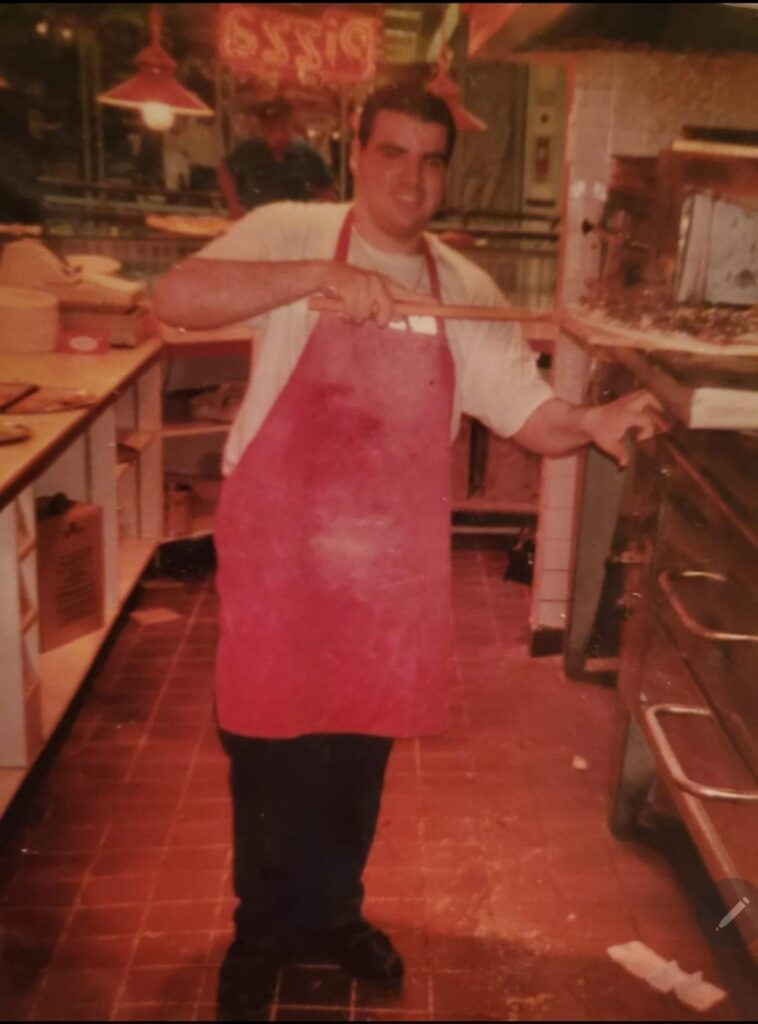

Alessandro Spennato’s life is incomplete without pizza and the mall.

His story began at a food court of a small town mall in the heart of Delaware County.

“I went from the hospital to the mall and then home, because my father had to go check on the pizzeria,” Spennato said about his birth.

Spennato, now 45, is the owner of Sitaly To Go, a small pizza shop in Wilmington. He holds his origin story close to his heart.

But if it were a perfect world, Spennato would still be spinning dough inside of the Granite Run Mall. The only problem is the old two-level mall is dead. The Promenade at Granite Run, a mixed-used development, stands on its grave.

Many believe they can hear the mall’s death rattle. But some industry experts aren’t convinced. Barbara Kahn, professor of marketing at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School of Business, said malls and physical retail are evolving.

“They’re definitely not dying,” Kahn said.

As of 2023, there are 1,126 malls operating across the United States. According to the International Council of Shopping Centers (ICSC), the number of enclosed malls has been relatively stagnant over the past decade. Other forms of combined physical retail complexes dominate much of the country. For every mall, there are approximately 99 open air marketplaces, such as strip malls and lifestyle centers.

Glory days of Granite Run

Spennato’s father Luciano immigrated to the U.S. from Italy when he was 13. At the age of 18, Luciano opened a Scotto’s Pizza franchise at Granite Run in 1974 — the same day the mall opened.

Gimbels and Sears anchored both ends, while Scotto’s ruled the food court. Members of the Spennato family held down the pizzeria for more than three decades.

“At one point, they tell stories that the top floor shook from how many people were walking on it,” Spennato said.

Positioned at the intersection of commerce and culture, the mall was so popular at one point that it was unimaginable to envision a world in which it could flop.

He recalled serving a slice of pizza to a young Kobe Bryant and witnessing Destiny’s Child perform on the ground floor.

But like many small town malls around the country, Granite Run’s success eventually ran out.

Spennato believes Granite Run’s death was self-inflicted.

“The decline was natural. When they talk about the internet and all that — that was totally natural. They made a conscious decision, though, to just speed up the killing of it,” Spennato said.

In 2011, Simon Property Group, the country’s largest owner of shopping malls, and co-owner Macerich fell behind on $115 million in debt on the property. The companies walked away. The banks soon took over. BET Investments purchased the sinking Granite Run for $24 million in 2013.

After acquiring it, BET told the Inquirer in 2015 that it would begin “de-malling” Granite Run in 2015. Executives argued the only way to turn around the struggling property was to engage in a $100 million project to repurpose it into an outdoor shopping center.

WHYY News reached out to BET Investments and Simon. Neither company responded to those requests.

History of the mall

Design critic Alexandra Lange, the author of “Meet Me by the Fountain: An Inside History of the Mall,” said the shopping mall was intended to be a “community magnet.” The newly built suburbs that sprouted after World War II were sprawled with young families needing a place to gather.

“That was what the mall was supposed to be,” Lange said.

Jewish architect Victor Gruen seized the opportunity after his arrival on U.S. soil. Gruen fled Vienna on the eve of Nazi occupation in 1938.

Inspired by a style of Viennese urbanism, he sought to develop an alternative to the car-reliant downtown commercial districts. His idea came packaged in a rather large, unassuming brown box — the enclosed shopping mall.

Gruen, a socialist, intended the mall to function like a town square in suburban communities where people didn’t reside stacked on top of one another.

His invention was a smashing success.

The mall became central to American life. It reached its pinnacle in the 1990s as teenagers became mallrats.

The Southdale Center, a brainchild of Gruen, is the first enclosed shopping mall in the country. It opened in Edina, Minnesota in 1956. The two-level complex, complete with a sky light and a “garden court,” promised to bring climate-controlled shopping year-round.

“Its selling point in the ads before it opened was ‘365 shopping days a year,’” Lange said. “So basically whatever the weather, in the cold of winter, in the heat of summer — you will always have a pleasant atmosphere in which to get your shopping done.”

She said archival news coverage revealed a budding love affair that many people had for the early mall.

Although local businesses saw the architectural marvel as a threat to their bottom line, the mall managed to attract nearby suburbanites in droves.

‘The death of bad retail’: What drove the decline in shopping malls?

Stephanie Cegielski, vice president of research and public relations for ICSC, acknowledged there are struggling properties.

“Because malls range everywhere from your very high-end malls with luxury retailers all the way down to general brands or even kind of mom and pop, it depends on what’s happening in that community as to how that property might be performing,” Cegielski said.

She said ailing malls can attribute their ills to a number of factors. Some fail to update their tenant mix to meet the needs of a changing customer base and demographic.

There are also the obvious economic factors. Kahn wrote the book on the retail apocalypse of 2017. Industry spectators panicked over concerns regarding an online shopping revolution.

Kahn said those fears were overblown.

“It’s not the death of physical retail,” Kahn said. “It’s the death of bad retail.”

Lange believes the Great Recession of 2008 was the beginning of the major visible downturn in the suburban mall. The economy was in ruins and people had less disposable income. Granite Run was a likely casualty.

There are three factors that undercut the mall business, Lange said. Online shopping, the decline of middle class department stores and the overabundance of malls across certain regions.

Instead of four malls sitting at each cardinal point outside of major cities, there were twice the amount.

“While the population of those cities were growing, they weren’t growing enough to support that much new shopping,” Lange said. “The new malls cannibalized the shoppers of the old malls, leaving the malls in the inner ring older suburbs without a lot of business and quickly trying to pivot.”

Cegielski believes e-commerce’s impact on shopping centers has been exaggerated.

“Pre-pandemic, there was about 9% of total retail sales that took place online,” Cegielski said. “That obviously skyrocketed in 2020 during government mandated shutdowns, but has come back down to about that same level. It’s about 11[%] or 12% of total retail sales now occur online.”

How pizzeria reign ended at Granite Run Mall

Spennato’s father Luciano managed multiple pizzerias, but the location at the Granite Run Mall was the crown jewel of the family. Even today, reminders of Spennato’s father’s pizza franchise pepper his wall opposite the cash register at Sitaly To Go.

Spennato said it was more fun to go to the mall and work as a teenager than stay home.

“We walked around the mall like we were superstars, because everybody knew that [we were] Luciano’s kids,” Spennato said.

When the Rouse Company first opened Granite Run in August 1974, Luciano had a non-compete clause in his contract, guaranteeing Scotto’s as the sole pizzeria in the mall.

Things began to crumble in the 1990s. Customers were beginning to fade. Retail rent space was beginning to rise.

Mall owners played hot potato with the property. It changed hands couple times before Simon acquired it alongside Macerich in 1998 as part of a joint venture.

Spennato said Simon initially had plans of creating a food court downstairs. In 1999, mall ownership asked Luciano to move Scotto’s into the new expected dining area..

He signed a lease. Then Simon canceled those plans. The company then asked Luciano to cancel the lease. He agreed to do so, but only after the company sent him a new lease for him to stay upstairs — where the pizzeria had stood nearly three decades.

Simon refused.

“They just wanted him out,” Spennato said.

Spenatto said Luciano ended up suing them, but an army of lawyers proved too much to overcome. Litigation was far too costly.

Luciano left willingly in 2005 at a time when his monthly rent approached the $16,000 mark.

What does the mall’s place in pop culture say about us?

Matthew Newton wrote “Shopping Mall” based on his experiences growing up in Pittsburgh as the son of a former retail worker at the Monroeville Mall. The shopping center was the setting of the original Dawn of the Dead film in 1978.

The themes within the movie coincidentally apply to the way people consume the nostalgia propping up the mall today. The mall, at least as a cultural moment, is immortal.

“Even though they — as they die, as they begin to close or even begin to become depressed and economically impoverished or whatever might be — people still have this desire to go there,” Newton said.

His earliest memories are his family coming to the mall to visit his mother at the department store. Newton met his wife there. During the Great Recession, he was laid off from his job as a writer for a trade magazine. Instead of immediately going home to break the news to his family, Newton relied on “muscle memory.”

“I was like, ‘I’ll give it a minute before I go home to break the news to my wife,’ and then I walked around the mall for half an hour or something like that because I was just clearing my head,” he said.

His story is not unique. WHYY News solicited hundreds of responses from people in the greater Philadelphia region about the role that malls have played in their lives. It is where many people get their first jobs, fall in love and even walk around in their senior years.

What does it say about America that one of the most popular places to hang out and relax just so happens to be the same place we shop?

“I think it is capitalism, but I think it’s a little bit more than that because I think it’s like that adrenaline rush people get from going out to shop,” Newton said.

Oversaturation is as easy as ABC: ‘Just by nature of capitalism, somebody’s not going to survive’

Mall rents are close to an all-time high, according to Adam Cummings, a retail occupier mall practice leader for CBRE. He said its because in the aggregate, occupancy is still relatively low.

“If there’s very little vacancy and they’ve got three or four guys that are all fighting over the same space, they have no incentive whatsoever to bring that rent down,” Cummings said.

David Putro, senior vice president of commercial real estate analytics at Morningstar Credit, said the “malls that are not going to survive the cycle are the ones that are recognizing just now that these changes have to be made.”

Putro noted that location is playing a huge role in the success of some malls. He used the Montgomery Mall as an example. Montgomery, which is flanked by both King of Prussia and Willow Grove, has been unable to keep its head above water.

“No one is building a mall anymore. The number of malls in the country right now is the maximum there will ever be in this country ever again. It only goes backwards from here,” Putro said.

Cegielski believes many parts of America are oversaturated with malls.

“When suburbs were built over the last 50 years, every kind of new community, they would put them all there or some new shopping center there,” Cegielski said. “And so if the market is saturated — just by nature of capitalism, somebody’s not going to survive.”

She said it can be an opportunity.

Far from a natural death

The mall isn’t dead, at least as a whole. However, what is clear is it has moved far away from the intended vision of its creator. Gruen had publicly disavowed the mall in 1978. He balked in disgust when he returned to Vienna to find a “gigantic shopping machine.”

His intention to give American suburbs a town center backfired. Lange said there’s still hope — for Gruen’s vision and for the mall as an institution.

Unfortunately for Spennato, that hope seems to have perished.

The mall called to him again in 2009. He tried to resist the urge to return to the food court. But the memories and nostalgia of a beloved family business outmatched his will power.

“My father told me when I wanted to go back to the mall, ‘Don’t go do business with these people,’” Spennato said.

He admitted his naivete got the best of him.

“I felt like he got wronged and I went back for revenge like ‘I’m gonna show them,’” Spennato said.

Spennato opened Sandro Pizza at Granite Run. At the start of his leasing agreement, he was dishing out $4,000 a month in rent.

But, he soon realized he was on a sinking ship — forced to pay an escalating rent to keep the lights on while his landlord began the process of de-malling.

He was there when the mall closed in 2015. Spennato estimated he had given mall ownership nearly $200,000 in rent. His landlords got to walk away largely unscathed.

“I could have totally accepted it had it had been a natural death, but when I know that they purposely killed it, it bothers me,” Spennato said.

Whether malls are dying or evolving might be a matter of perspective — or it might not matter at all. Spennato’s mall is dead. It’s not coming back.

Luciano, toward his later years, waded into the restaurant construction business.

“This is his last gift to me,” Spennato said, gesturing toward Sitaly To Go. “Building this for me.”

Spennato opened his new pizzeria at 1806 Marsh Road in September 2019. His father died in May 2021 due to COVID-19 at the age of 65.

These days, his rent is $1,700 a month. Despite malls still tugging at his heart, Spennato said he’ll never pay a big rent again.

“It’s just not worth it,” Spennatto said.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.