Airbnb rental leads to squabble, new regulations in Bucks County

Zoning laws that restrict hotels or boarding houses often don’t apply to short-term rental arrangements. But pending changes in Buckingham Township echo a national trend.

Listen 5:54

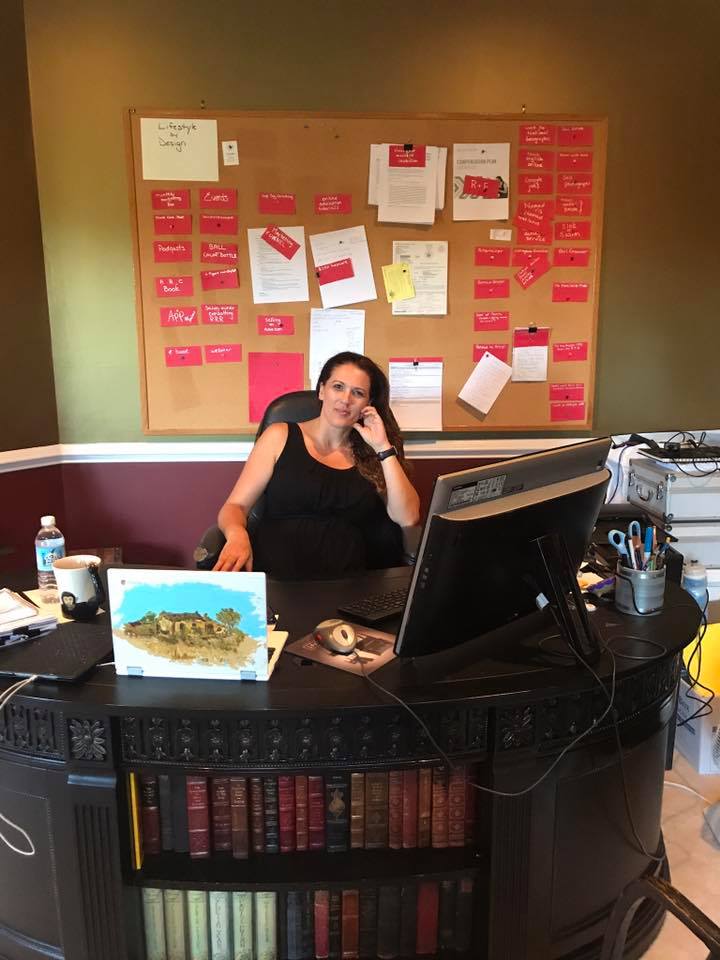

Donna Roggio sits in the office at her home in Buckingham. Township officials have ordered her to stop renting her house through Airbnb. (Laura Benshoff/WHYY)

During the golden hours of late afternoon, the kids are out in Buckingham Forest, a planned community in Furlong, Bucks County.

Some roam on bikes and scooters. Others, wearing ballet tights or football pads, load into waiting SUVs that spirit them away to practice.

Houses for sale in this brick-and-stucco Toll Brothers development go for north of a half-million dollars. Mercedes and Teslas share the road with Fords and Toyotas — as well as fleets of lawn care trucks.

“I bought this house as an investment,” said Donna Roggio, sitting on a lounge chair inside her spacious four-bedroom house on Green Ridge Road. “And then, my life changes.”

Roggio was recently-divorced when she bought the house at the peak of the market. She and her now 15-year-old daughter, Riley, lived there for several years, but Roggio’s life began moving in a different direction. She traveled regularly to visit her now-fiance, who lives in Hamburg, Germany. A few years ago, she resolved to sell the house, which overlooks a picturesque dip in the landscape. When it didn’t move after a year, she listed it on Airbnb for $225 a night in 2016.

More and more, renters and hosts like Roggio are spreading outside of major cities in the U.S., according to a report released by Airbnb earlier this year.

“Rural and suburban hosts are some of our fastest-growing populations, even faster than in urban areas,” said Andrew Kalloch, the company’s director of public policy. In Pennsylvania, 12,000 people list properties on the site.

But homesharing and homeowners associations don’t always go together. Tensions over rentals outside of Philadelphia have led to quarrels — and new regulations — in this and other communities.

Discord in the neighborhood

Sitting at the computer in her home office, Roggio scrolls through the people she has hosted. While there are hotels and bed and breakfasts in nearby Doylestown and New Hope, Roggio said she had no trouble finding guests for her corner of Bucks.

“I had somebody come for a 30th birthday, who grew up going to Peddler’s Village … I had a family from Ireland coming in to stay for their brother-in-law’s wedding, I had a family from China,” she said, reading through the list.

The money helped cover her mortgage, and the short-term rentals kept people in the house when she traveled. After a few months, she left to visit her fiance, who lives in Hamburg, Germany. When she returned, there was a cease-and-desist letter in her mailbox from the township that Furlong is part of.

“This letter shall act as a formal notice that you are in violation of the Buckingham Township Zoning Ordinance Requirements,” it reads. “You are hereby ordered to cease the operation of a bed and breakfast immediately.”

Her neighbors Frank Jonas and Brendan Noone had gone to a meeting of the township supervisors and complained about many as 10 properties listed on Airbnb within 2 miles of the development.

Jonas, who lives next to Roggio, declined an interview, as did the people who answered the door at Noone’s address. But the meeting minutes preserve their concerns.

“Mr. Jonas is concerned about his family’s safety with transient people coming and going next door,” according to that record. Noone “found another local residence renting their basement for $300 a night. He asked what could be done about this.”

Craig Smith, the solicitor for Buckingham Township, said the rentals also touched on something beyond safety concerns, by shattering expectations of what people think is allowed where they live.

“If someone is renting a room or a house out on a 20-acre farm, no one really knows and no one really cares, but I think if you’re in a development … where people are 15-20 feet away, that’s a whole different issue,” he said.

Meanwhile, Roggio was stunned — and out nearly $5,000. “I had to cancel four people,” she said. “It’s a ton of money for me. It’s a ton of money for anybody.”

‘Yard sale doesn’t turn your house into shopping center’

But what Roggio and others hosts in Buckingham are doing may not be against the law.

The township, like others across the region and country, has stumbled into a legal gray area. Existing zoning laws restricting hotels or boarding houses often don’t apply to short-term rental arrangements.

“If you have a yard sale at your house, it doesn’t automatically turn your house into a shopping center,” said Kalloch, whose role involves trying to get local governments to work with the company. He pitches Airbnb as a nonthreatening form of business growth, run by neighbors you know and trust.

So far, Pennsylvania’s Commonwealth Court has agreed with that sentiment. Three times, homeowners in the state, all in the Poconos, have appealed orders from their municipalities to stop renting through sites such as Airbnb or HomeAway. So far, the courts have sided with homeowners.

That pushed Buckingham and other townships to explore tightening their laws, to specifically bar these rentals. Smith said Buckingham officials have gone through two drafts and may vote on new zoning regulations before the year is out.

To the north, Tinicum Township is doing the same, after neighbors complained about houses near the Delaware River rented out for raucous parties. In New Jersey, some lawmakers have introduced bills to help any municipality in the state rein in short-term rentals.

Sharper oversight may restrain short-term lodging

And, across the country, places from the District of Columbia to Cambridge, Massachusetts, have debated some form of restriction to keep housing prices reasonable and make sure people do not turn residential properties into short-term rental businesses.

These regulations may be slowing the growth of Airbnb, according to a survey this year by the Swiss bank UBS.

For Donna Roggio, the debate soured what was once a pleasant community. She said she hasn’t talked to the neighbor who complained in more than a year.

“You feel like you’re friends with them. You barbecue with them, you cut their kid’s hair, and then you realize …,” she trailed off. “It’s the fear. People are so fearful.”

But, after several months off Airbnb she is sharing her home again. Roggio went to the township and demanded to know the length of a “short-term” rental. Eventually, officials told her three months.

On Airbnb, Roggio found Elena Ghisu, a divorced mom of two, who needed a place for her family to stay while the townhouse they’re moving into is built. Ghisu had some reservations about living with a stranger, but the arrangement has worked well for her — both financially and for her kids.

“Still very close to their dad, close to their school, close to work, and plus the price was right! I could do this,” she said.

By the time they expect to move into their new home at the end of the year, the township may have passed new rules barring Roggio and anyone else from taking more rentals.

Roggio plans to leave when her daughter graduates from high school, to join her fiance in Europe. Even there, Berlin and other cities have cracked down on the Airbnb homes she likes to rent when she travels.

This is a corrected version. A previous one incorrectly stated the timing of Roggio’s divorce and purchase of the property.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.