Advocating from the ground up- Delaware’s Sex Trade, Part 2

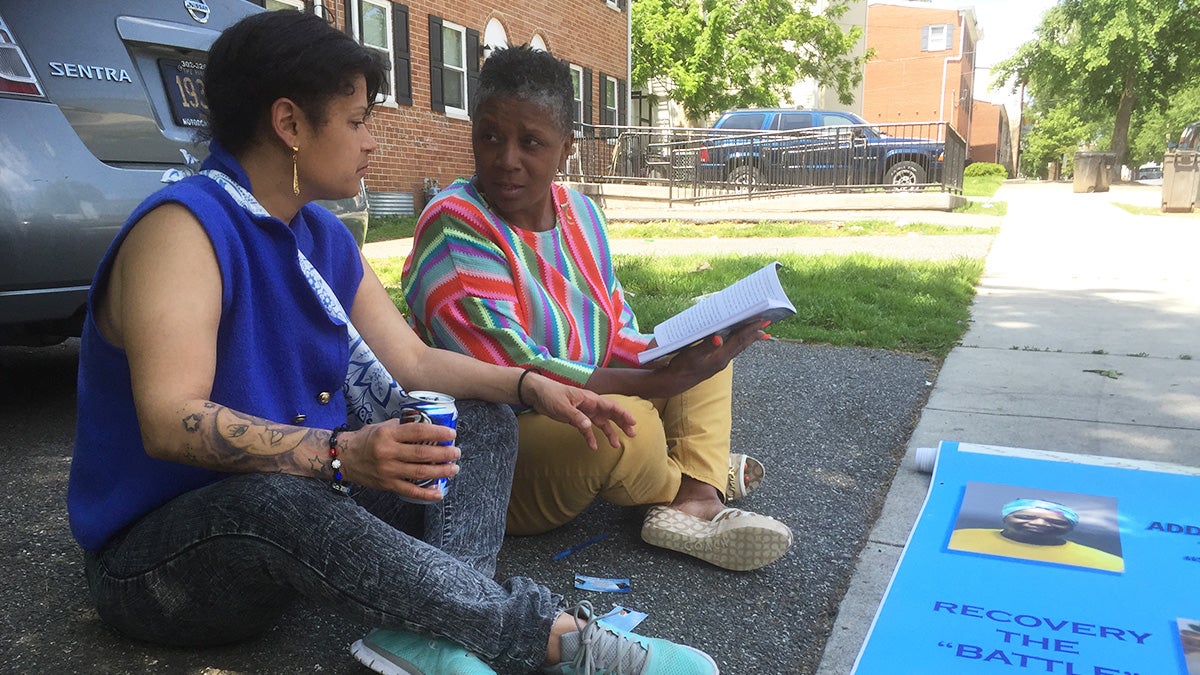

Edwina Bell counsels women who are involved in prostitution. (Zoë Read/WHYY)

For the past several months, WHYY’s Zoë Read has been interviewing experts about prostitution and sex trafficking in Delaware. WHYY will publish a chapter of the story each day of the week. To read the series from the beginning click HERE .

The Road to Recovery

Edwina Bell is a confident, straight-talking, stylish woman, who is as bold as her sharp, long, red fingernails. She has a passion for helping people, and sharing her love for God.

But it took Bell a long time to become the woman she is today. For years she struggled with drug addiction, and was involved in prostitution while living in Philadelphia.

Bell said she was sober when she first entered the life at 18 as a way to make more money, and to receive the attention she felt was missing from her life. But as she became addicted to crack at 25 she used prostitution to support her habit.

Bell said she ran away from johns who refused to pay for her services, jumped out of windows and cars to escape dangerous johns, pimps and drug dealers, hid in closets, was left behind in abandoned homes and was physically attacked.

“You always to some extent know the risk. But we have this mentality…this invincible mindset. We were driven by addiction, so that kind of stuff wasn’t fearful for us,” she said.

“I didn’t start getting nervous until the conversation went wrong or if there was a tone in their voice that kind of said, ‘Bitch I’m going to hurt you.’ Then we try to bring on the tears—anything to distract them or bring them off course. When we get out those situations we’re thanking Jesus, and then we’re looking for another high to forget it and we put ourselves back in the same situation.”

Bell said she knew she was on her way to turning her life around when one day she began crying in the middle of performing a sex act on a client.

“Something says, ‘I just can’t do this no more,’” she said. “I tried to commit suicide a couple times. But I knew I was getting to that point when that happened.”

Bell said one evening she got high with her step son, whose father was 25 years her senior and a former trick. She said at the end of the night her step son became verbally abusive, so she ran out of the house. When he began chasing her, Bell said she hid underneath a parked car.

“My face was on the ground, my life flashed before me,” she said. “That was literally my rock bottom.”

Bell said the police took her home, and her husband encouraged her to seek a rehab facility.

“When I called the hotline I said, ‘I know I need help, I want help,’ and I haven’t looked back,” she said.

Bell said rehab and the church helped her get on her feet.

Now the advocate and Doctor of Ministry candidate gives other women involved in prostitution some straight-talking advice: “Stop giving head and use your head.”

Bell said she mentors as many as five women at once or as few as one in a three-month period. She also has been invited to speak in facilities like women’s prisons. Bell said she knows there are more women out there who need her help.

“Sometimes it’s very painful for them to talk about, and my heart goes out to them, because I know where they are,” she said.

“When I share my experience, and how I used the services that were available, and the willingness I had not to do one more trick—and I share with them how it took for me to be under a parked car—they leave with hope.”

Bell said she helps women understand the deep root causes that led them to prostitution, refers them to community resources and encourages them to adopt positive habits in their daily life.

“Often the prostitutes talk about being homeless, they talk about not having medical coverage, there’s also some discussion about depression, suicide, the need to find a way out—and in their mind there is no way out,” she said.

“We can and do recover if we have the willingness to say, ‘Enough is enough,’ because it ends in three places—jails, institutions or death.”

________________________________________________________

Bell drives through low-income neighborhoods of Wilmington, searching for women on the streets—those who are standing around, waiting for men to make eye contact with.

As she drives she points to the old warehouses and factories where she said syringes and condoms are frequently disposed of.

As Bell heads toward New Castle Avenue she finds a woman sitting on a stoop with an older man.

Bell, who is wearing black stud earrings, a leopard print jacket, beige pants and leather heels, clip-clops confidently toward the woman on the stoop.

“Remember me?!” she shouts with a large smile on her face.

Bell hands her a business card and her self-published “From Crack to Christ,” which documents her personal journey through her journal entries.

The woman is friendly, but informs her she’s “cock blocking.”

Bell, still smiling, is understanding of her need to make money.

The woman says she will call her, but that getting out of the life is difficult.

“I’m broke, I’m hungry and I need money,” she said.

Bell said she never pushes the women, but gives them the opportunity to call her when they’re ready to take the first step on their own terms.

When she travels toward the west side of Wilmington she finds another woman in the Quaker Hill area who needs a ride to work.

During the ride the woman said she’s afraid her boss will find out she’s using drugs again. She said she always used recreational drugs, but became hooked on heroin after her husband cheated on her. She said like most women struggling with addiction, she often exchanged sex for money or drugs.

She said she was clean for nine months, but recently relapsed.

“I’m upset at myself for relapsing,” said the woman, who has been trying to get custody of her daughter for three years.

Bell said she doesn’t believe prostitution itself has changed much over the years, but believes the drugs have become more dangerous and the women are in more despair than ever before.

“Basically it’s the same, but it’s worse in terms of the outcome and level of desperation,” she said. ‘This is all I know.’ That’s what I hear the most. ‘I’ve been doing this since I was 14, this is all I know. If they want to change it, tell them to stop coming over here and buying it.’”

On a Tuesday afternoon Bell went to a Wilmington McDonalds to meet three women she met on the streets during her outreach—including Erica, the transgender woman who has been involved in prostitution since she was 16.

Only Erica showed up.

It was the 1st of the month, and it was warm outside—two factors Bell said make good business for the women.

At these meetings Bell and the women introduce themselves, talk about their lives and sometimes express their deepest feelings. Bell provides encouragement, and offers information on resources, like counseling.

Erica talks about the pain she often feels, occasionally pausing her speech to gaze out the window and stare at the street. Bell places her hand on Erica’s arm, providing some encouraging words. She tells her they were brought together by destiny.

There is a sense of hope in Erica, who smiles when she talks about everything she wants to accomplish—like getting a GED.

The following week Erica said she agreed to meet Bell because she presented her an alternative she didn’t know was possible.

“I related to a lot of the things she went through, and her being from Philly,” she said. “I really thought it could be me, I could start changing my life and helping other girls on the street.”

Chrysanthi Leon, a professor of sociology and criminal justice, women and gender studies and legal studies at the University of Delaware, has researched prostitution for several years.

In 2010, she conducted a study at the request of judges and others in the state who wanted to learn more about a perceived problem of prostitution in Delaware.

Leon and her team interviewed hundreds of women involved in prostitution in Delaware and gave recommendations on the best way to serve them.

“We found what women needed was housing, women needed employment, women needed access to educational opportunities and they needed legal assistance to get their children back or get their record expunged,” she said.

Leon has published a series of articles about approaches to prostitution recognizing the resilience of the women involved. She said services are best served when they’re not coercive, allowing women to seek the help on their own. Leon said social services, and peer-help such as Bell’s work, often can be more effective than authoritative programs.

“Many women in Delaware involved in prostitution talked about the incredible stigma and shame treatment providers and judges and police officers showed them, even when they were participating in programs that were about helping them,” she said.

“When we put people within programs to ‘quote un-quote’ help them, without their full agency or readiness for change we have to recognize that’s a coerced situation we’re putting people in, and we can see from a social work perspective it reduces the efficacy of those kinds of interventions.”

Bell said there needs to be more services with longer hours in Delaware to serve this population.

“Often when we do want help the agency has closed down, the church is locked up and there’s no place to go,” she said. “So what seemed to be a moment of hope turns into hopelessness.”

Bell also said while there are services available, some of the organizers only want numbers met, rather than helping their clients with genuine care.

“Yes, the services are available. Are there people who are going to look at us like human beings, treat us like human beings? That level for respect for another human being without criticism is crucial,” Bell said. “Even if you don’t say anything to me, the way you look at me could send me out the door.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.