ACLU files last-minute suit arguing Pa.’s Marsy’s Law amendment is unconstitutional

Marsy’s Law would insert a bill of rights for crime victims in Pennsylvania’s constitution. The ACLU thinks it’s too sweeping and would need to be broken into parts.

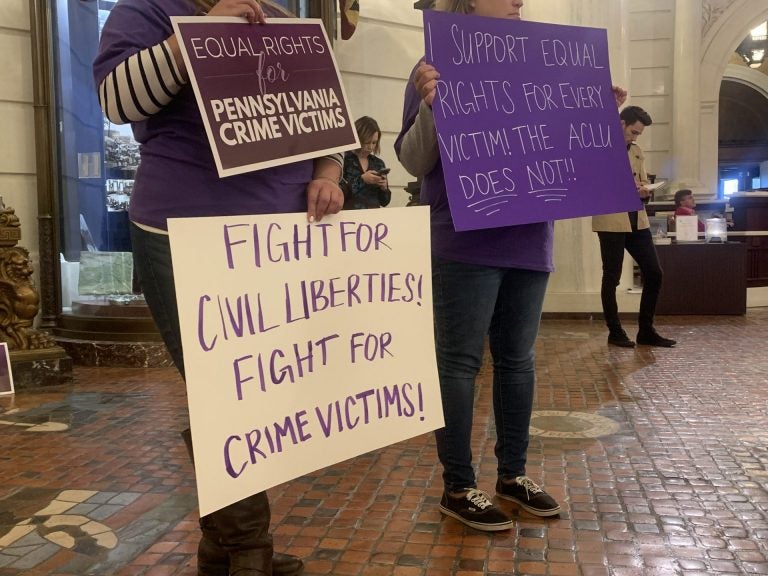

File photo: Supporters of Marsy's Law held signs in protest during the ACLU's press conference announcing its lawsuit. (Katie Meyer/WHYY)

The American Civil Liberties Union on Thursday filed an eleventh-hour challenge to a proposed constitutional amendment set to be on the ballot next month.

Pennsylvania’s ACLU chapter argues the measure — known as Marsy’s Law — would affect too many parts of the state constitution, a violation of laws governing statewide referenda.

Marsy’s Law would essentially add the commonwealth’s existing crime victims’ bill of rights statute to the constitution. The language of the measure seeks to ensure those rights aren’t ignored. For example, it would allow a victim to ask a court for a new hearing if the victim wasn’t given an opportunity to speak at the first.

The ACLU has long opposed Marsy’s Law, arguing the amendment is too vague and could compromise the rights of the accused.

The group is bringing a suit on behalf of the League of Women Voters of Pennsylvania and an individual plaintiff to keep the amendment off the November ballot.

“It’s an omnibus bill that amends three different articles, eight different sections, and one schedule to the Pennsylvania Constitution,” attorney Steven Bizar said. “[It] requires the voters of Pennsylvania to take a single ballot question, yes or no, rather than affording them the right to vote separately on each amendment.”

The ACLU’s argument is based on Article XI of the Pennsylvania constitution, which covers constitutional amendments. The article says that if the legislature wants to submit two or more amendments to the constitution, those changes “shall be voted upon separately” in the subsequent referendum.

Marsy’s Law, the attorneys say, is being presented as one change—an addition to Article I of the constitution—but could significantly affect the way other parts are interpreted.

As an example, ACLU Deputy Legal Director Mary Catherine Roper pointed to a clause in Marsy’s Law that says a victim doesn’t have to respond to any request for discovery—i.e. fact-finding in a case—from a defendant or a defendant’s lawyer. But existing language in the constitution says a defendant is entitled to compulsory process to get witnesses for their defense.

“I don’t know how you could say that that does not rewrite the section on compulsory process,” Roper said.

Jennifer Storm, the state Victim Advocate and a key Marsy’s Law backer, said she thinks the challenge is baseless and insisted that the ACLU’s one-subject concern was addressed when the amendment was drafted.

“We’re amending Article 1 of the constitution,” she said. “It was very clear in the legislature, it’s very clear in the ballot question.”

Storm also questioned the ACLU’s timing—noting that Marsy’s Law was debated and voted on during two legislative sessions and, per amendment rules, its language didn’t change in all that time.

“It’s disenfranchising voters, quite frankly,” she said. “There are people who have already voted on this, ballots are out, people have already submitted their absentee ballots.”

There is some precedent for the ACLU’s argument.

In 1999, the commonwealth court struck down an amendment that sought to make it harder to pardon people sentenced to death or life in prison—ruling it actually made five changes to the constitution.

“The single ballot question…described four amendments and neglected to describe a fifth,” the majority opinion in that case said. “If these amendments were so interrelated that they needed to be adopted as a unit, they should have been submitted to a constitutional convention. Otherwise, each modification, deletion, or addition should have been submitted to the voters as a separate question.”

In that case — and in the ACLU’s new one — the plaintiffs raised a secondary dispute, arguing that the ballot question was not adequately detailed, given the extent of the proposed amendment.

The ACLU is asking the commonwealth court for an expedited opinion. It’s not clear what will happen to the ballot question if the court rules in the group’s favor ahead of the November 5 election, as many counties have already finalized their ballots.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.