Abatements, assessments, and unanswered questions from land value shift in 2017 property taxes

Ever since the Office of Property Assessment (OPA) released the new 2017 property assessments, unanswered questions have lingered regarding whose tax liabilities increased and why.

The 2017 assessments shifted more value toward land for 58% of properties, and for the vast majority of those properties, building values were reduced by an equal amount. The shift had no effect on the total tax liability for most of those property owners, but it did increase the tax liability for property owners with 10-year tax abatements. That’s because owners of abated properties are still responsible for paying taxes on their land value during that 10-year period, so a higher land assessment equates to a higher tax bill.

OPA has maintained they were only carrying out a routine data-cleaning project, updating land assessments that had been criticized as inaccurately low even after the 2013 Actual Value Initiative. But that hasn’t quelled the debates over whether the city is deliberately trying to devalue tax abatements in pursuit of more revenue.

A new analysis of the 2017 assessment data from Pew’s Philadelphia Research Initiative won’t settle the debate either, but it does put the scope and the geography of the tax increases in context.

Tax impact of the land value shift

Pew found the 2017 land value shift resulted in a higher tax liability for about 4% of residential parcels– 23,157 out of a total of 579,447 properties.

That’s distinct from the total number of properties that saw a tax increase in the 2017 assessments from higher overall property values–about 14%. Pew is only looking at the effect of the land assessment changes.

This shift alone will bring in $13.3 million, or around 1% of the city’s total property tax haul.

Two types of tax increases and variation

There were two ways the shift in land value could have increased property owners’ tax liability.

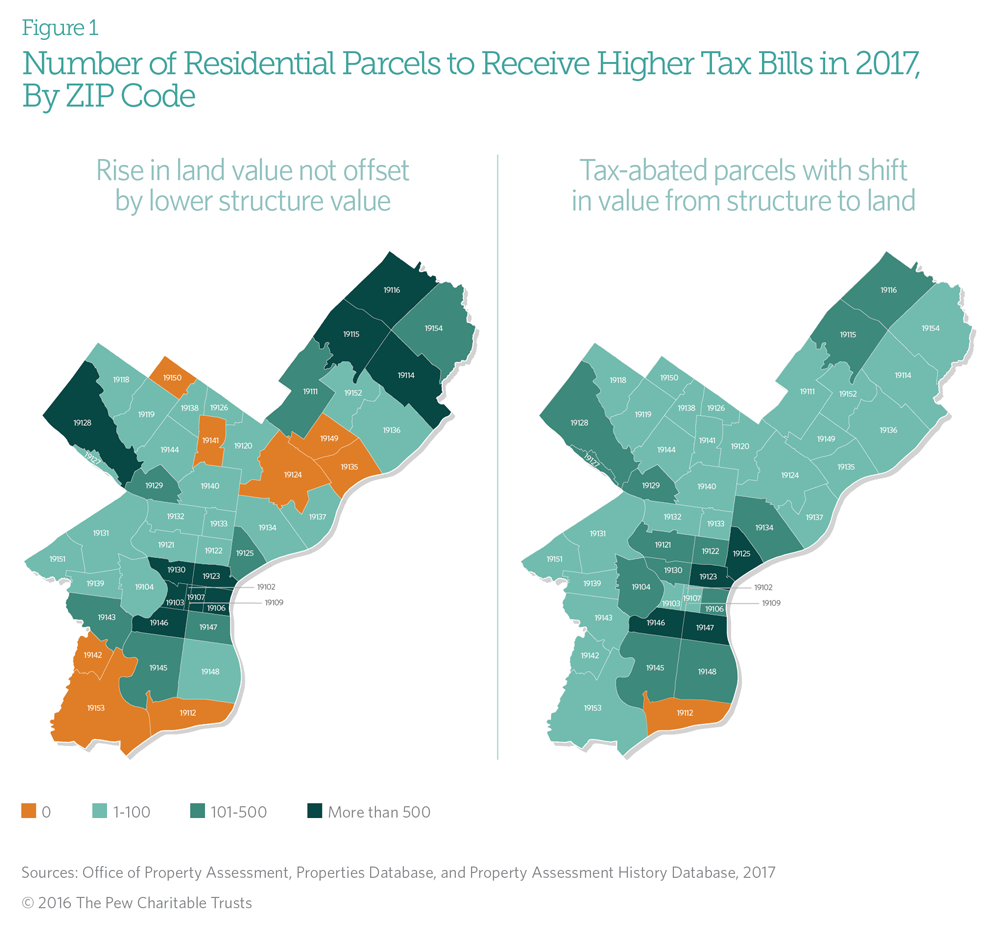

The primary way–accounting for 71 percent of cases, and affecting 16,395 properties–was that “the higher land valuation was not offset by a lower structure valuation, resulting in a larger overall assessment.”

Properties that fell into that category were concentrated around Center City, Roxborough, and the far Northeast. A little over half of them will have tax abatements or exemptions in 2017. They account for $7.8 million of the $13.3 million increase in property tax receipts.

The other way the land value shift caused increases in property tax liability was through higher land assessments at properties receiving the 10-year tax abatement, which increased the non-abated portion of these property tax bills. This accounts for about 29 percent of the properties with higher property taxes due to the land value shift —6,762 in total. These make up about 1.2% of all city parcels, and would contribute an additional $5.5 million in 2017, barring appeals.

There were 15,118 parcels receiving 10-year tax abatements in Philadelphia in 2016.

Real estate markets are spiky, and within those two categories of tax increases, the scale of increase varies.

For the first group—properties where land assessments increased without an equivalent decrease in structure value—the median increase was $266, and the average increase was $477. According to the quartile breakdown Pew provided to PlanPhilly, the 25th percentile saw an increase of $134, and the 75th percentile was $498.

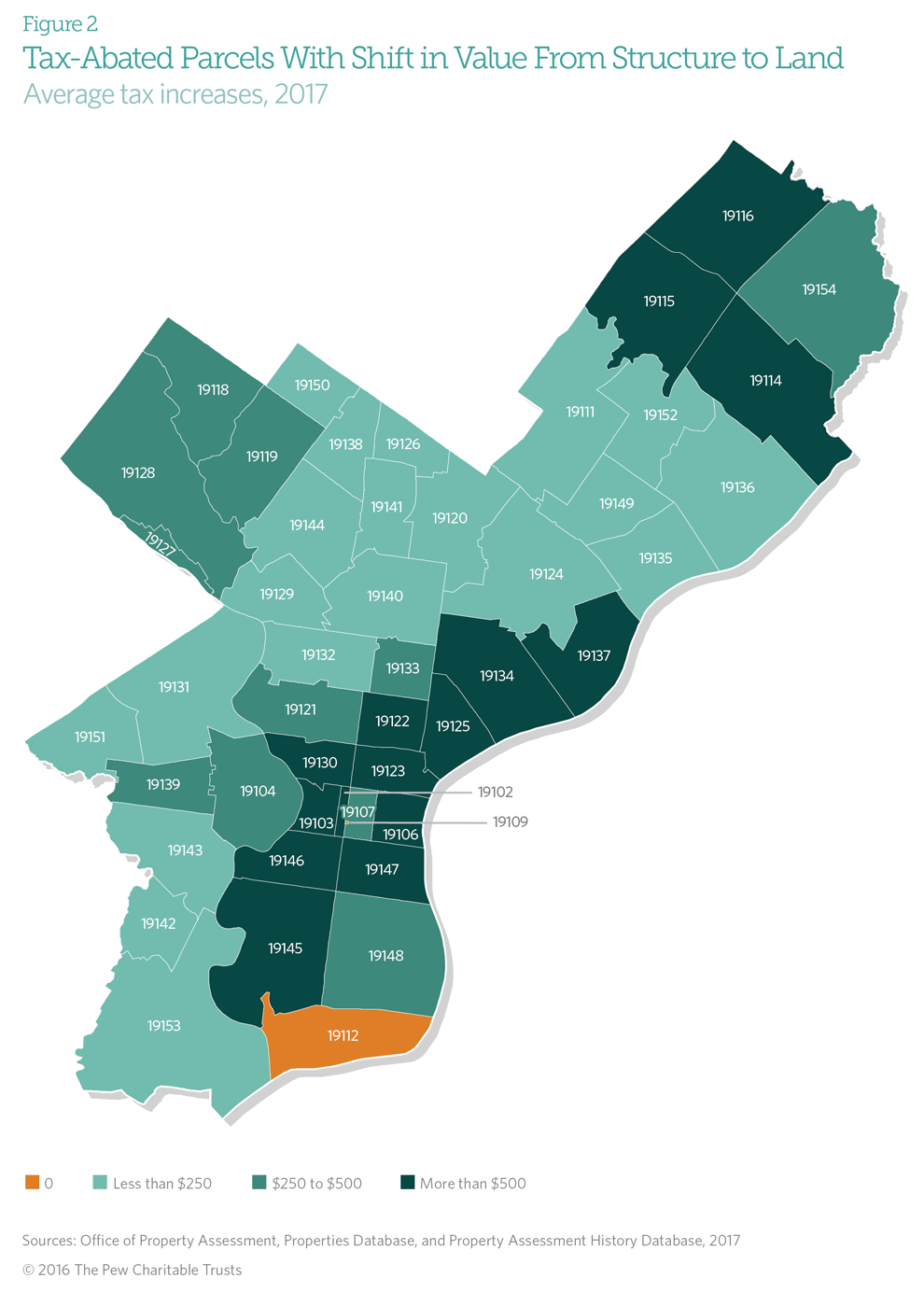

In the second group, where taxes increased solely due to a shift in value from the abated structure to non-abated land, the median increase was $480, and the average increase was $816—a much more significant spread than for the first group. The 25th percentile saw an increase of around $190, while the 75th percentile increased around $1,052.

Pew visualized this change throughout the city, mapping how the two types of tax increases associated with the shift in land assessments were geographically distributed.

Unanswered Questions

One issue left unsettled by Pew’s analysis is whether OPA’s land assessment methodology is accurate or fair.

Several observers have noted large variations in land assessments between similar properties on the same block, or in similar parts of a neighborhood, where one would expect land assessments to be roughly the same on a square foot basis.

Greg Phillips of the real estate analysis site RentHub published an analysis of the 2017 assessment data on his blog, observing that OPA appears to have derived land values as a percentage of building values, rather than the location characteristics that are known to drive land values.

Phillips looked at the correlation between 2017 land values and 2016 building values for the ‘land shift’ properties, and found that “the 2017 land assessments in this cohort can actually be better explained in terms of their previous building value than their previous land value.”

Deriving the value of a piece of land based on a single building that sits over top of it is weird, argued Ruokai Chen in an overlooked op-ed for The Spirit which pegged this methodology as the best explanation for some of the big variations in land value on individual blocks.

Dense as all of this is, it has some important implications for tax fairness. It makes sense that newly-constructed buildings would have higher values than older properties of similar size and location, all else being equal, but the same isn’t true for the underlying land.

And yet, if these outside analyses are correct that OPA is deriving land assessments substantially from building values, OPA is essentially saying that the land underneath a newly-constructed building is worth more than the land under a neighboring older building on an identical lot. That doesn’t make sense, and it has the effect of devaluing tax abatements beyond what is warranted by OPA’s adjustments.

In his original interview with PlanPhilly after the 2017 assessments came out, OPA’s chief assessor Michael Piper hinted that this is one of the assumptions in his model, saying that it incorporated a principle that developing a piece of land makes the land component itself more valuable.

“We have to recognize a principle that says, when you have a piece of land that’s undeveloped, it tends to become worth more once it’s developed,” he said, “That’s sort of a principle of real estate valuation that’s a little bit hard to conceptualize for some folks, but that’s what we did this year.”

But Piper also maintained that his model was primarily focused on “the contributory value of land” and location attributes. Asked about the variation in land values between individual parcels on a block, he said he wasn’t able to generalize, and would need to look at individual instances.

“That’s probably the most common question we get,” he said “The assumption sometimes starts from ‘everything is the same’ but there may be something else we took into consideration about the properties. In some instances, we may need to make some adjustments.”

OPA is mailing assessments for vacant land parcels this week, and are planning to release an updated data set next week, so we will soon have a more complete picture of the property tax changes for further analysis.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.