A Yiddish take on the national pastime

The new exhibition at the National Museum of American Jewish History, “Chasing Dreams: Baseball and Becoming American,” features a large wall graphic of a square inside a pair of concentric circles separated by small diagonal lines. There are Hebrew letters next to small symbols.

“It looks like the sephirot, which in Jewish Kabbalah is the way you understand the mystical ladder that we use to reach God,” said Rebecca Alpert, a professor of religion at Temple University.

It’s actually a visual explanation of baseball. “I’m one of those people who sees baseball as much more than a game,” said Alpert, the author of “Out of Left Field: Jews and Black Baseball.”

The graphic came from the Aug. 27, 1909, issue of the Jewish Daily Forward, whose editors believed baseball was important for its immigrant readership to understand. They printed an explanation of the game in Yiddish, including a diagram of the field.

But something got lost in translation. This follows the description of how the pitcher throws a ball to the catcher:

“The reader may ask, doesn’t it happen backwards each time — the catcher becomes a pitcher and the pitcher becomes a catcher? Why should each one be called a specific name: one a pitcher and one a catcher?”

“It is this very Jewish attempt to understand the game. It has this Talmudic feel to it,” said curator Josh Perelman. “They took each of the minutiae of a baseball game and attempted to understand just that piece, and then layered onto it another piece. It’s almost as if they started in the grass and built out to the stadium rather than looking at it from above and describing it as a whole system with a set of rules.”

“Chasing Dreams: Baseball and Becoming American” drills down on baseball as a cultural gateway for immigrants trying to integrate into American life. It features the original sheet music of “Take Me Out to the Ball Game,” written by the songwriting team of Jack Norworth and Albert Von Tilzer — who was Jewish. Neither of them had actually seen a baseball game.

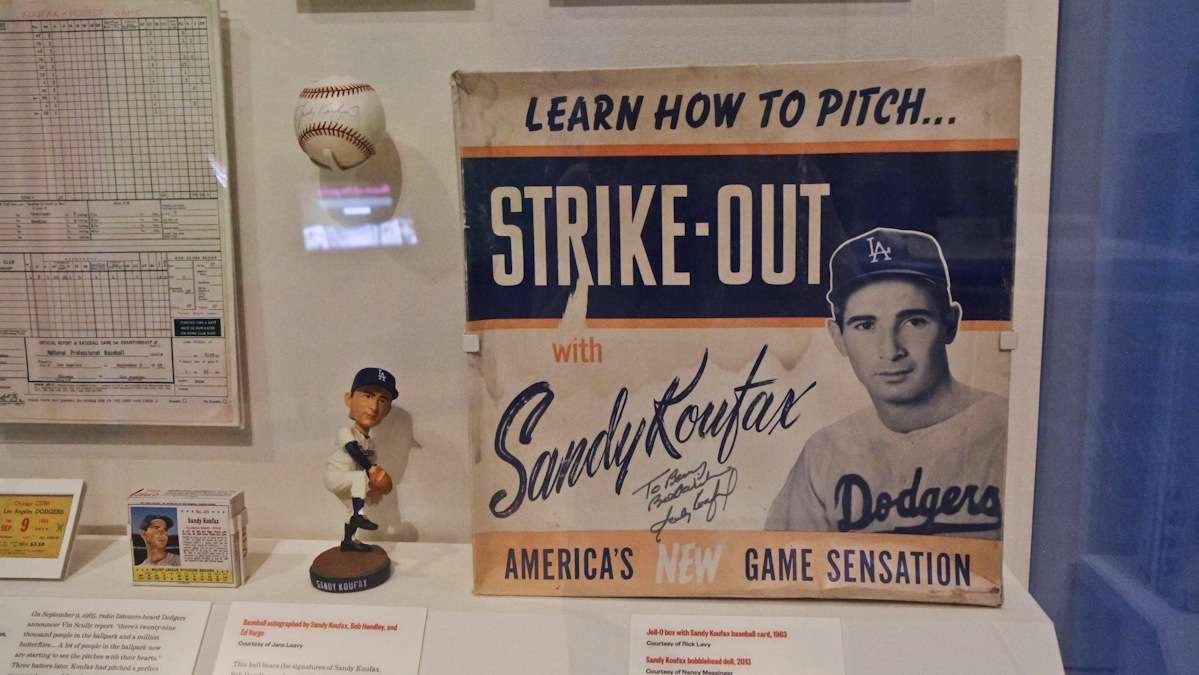

The exhibition features famous players like the homerun machine Hank Greenberg, known as the “Hebrew Hammer,” and pitcher Sandy Koufax — both of whom were reluctant to play on high holidays. It ranges from the first professional baseball player — Lipman Pike, a Jew who received $20 a game to play for the Philadelphia Athletics in 1866 — to Shawn Green, the recently retired Mets all-star who (like Sandy Koufax) refused to play on Yom Kippur.

The exhibition features Green’s dirty cleats from the 2012 World Baseball Classic qualifier game, when he played with Team Israel (which lost to Spain, 7-9). The spikes are still caked with soil from Florida’s Roger Dean Stadium.

“Baseball has been the thing that symbolizes who we are, and who we would like to be,” said John Thorn, the official historian for Major League Baseball and chief consultant for “Chasing Dreams.” He wanted to broaden the Jewish experience of the game to other minorities, including African-Americans and Latin-Americans, who used the game to locate themselves on the American landscape.

“We insist upon our being special, yet we long for acceptance,” said Thorn. “Those seem like contradictory goals, and baseball provides a wonderful stage for it.”

The exhibition runs until Oct. 26, when — with a whole lotta luck from the sephirot — the Phillies will be in the World Series.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.