A Voyage to Wyeth’s Magical Islands

The combination of Chadds Ford and Maine influenced Jamie Wyeth. Here’s a closer look at the New England part of his world.

Jamie Wyeth’s first major retrospective is on exhibit at Brandywine River Museum of Art through April 5. Displayed in three galleries, it is the most comprehensive survey of Wyeth’s art ever to be assembled. The traveling show presents a full range of Wyeth work, consisting of 111 paintings, works on paper, illustrations, and mixed media assemblages– collages of three-dimensional items.

The works depict the landscapes of the Brandywine Valley and coastal Maine, family members, fellow artists and friends such as arts impresario Lincoln Kirstein, pop artist Andy Warhol and superstar dancer Rudolf Nureyev. And there are, of course, many, many paintings of animals and birds. These works provide an in-depth examination of the artist’s stylistic evolution and showcase the diversity of an artistic career now in its sixth decade. Wyeth divides his time between homes and studios near Chadds Ford and those on Maine’s Monhegan and Southern Islands.

The Maine influence

Last summer, I traveled to the north country to capture the sights and feel of these magical islands. We’re queued up on the docks of the charming village of Port Clyde ready to climb aboard a 65-foot vessel, the Elizabeth Ann. With the passengers, mail and freight loaded, we steamed out of the harbor past Marshall Point lighthouse and a series of pine and spruce-clad islands before reaching the open sea to ply our way toward Monhegan Island.

Navigating among the schooners, lobster boats and other vessels that traverse the Gulf of Maine, we get up-close views of porpoises and families of brown seals frolicking in the sea or basking in the sun on Seal Rock. Hundreds of buoys mark lobster traps, each marker color coded to identify its owner. After an hour ferry ride, my wife Jane and I stepped off into a tidy coastal village and hiked up past the Island Inn that sports an American flag whipping atop its cupola.

Monhegan boasts impossibly quaint houses surrounded by colorful flowers. There are no cars and no paved roads, just narrow lanes and footpaths. A handful of tailgate-less work trucks haul pallets of building materials, propane, produce and food, beer, wine and other cargo from the docks to businesses operating on the island.

Barely a square mile in area, Monhegan is a hard working culture, where fishing and lobstering families still live and work by the tide clock. The summer resident population hovers around 200, but day-trippers can add another 600 or 700 to the mix. Winter is a quiet and lonely time; the island shrinks to its bedrock population of 65.

James Browning Wyeth’s connection to Monhegan Island– ten nautical miles off the mid-Maine coast– dates to the summers of the late 1950s when he first vacationed there with his father Andrew. They sketched together, and some of Jamie’s early Monhegan paintings– a bronze bell in particular– became some of his best-known work.

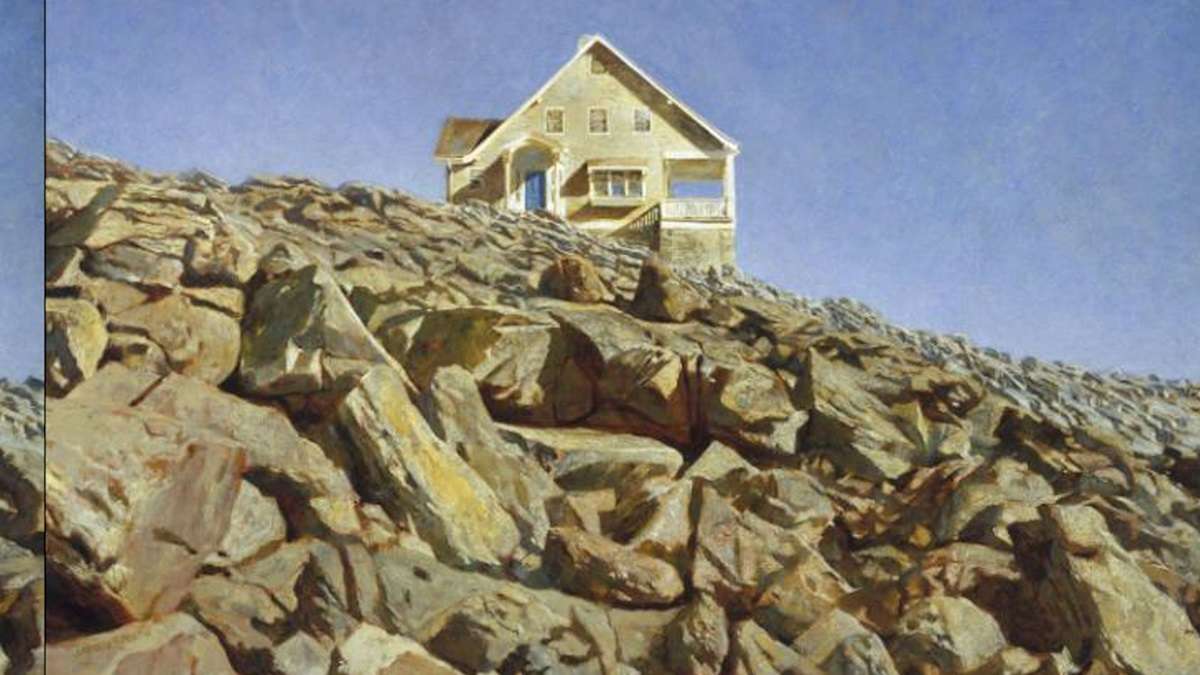

With its inspiring rocky landscape, rugged cliffs and dramatic ocean vistas, Monhegan has lured artists for more than 150 years. With proceeds from early-career sales in New York City, Wyeth purchased the cottage and studio that famed artist Rockwell Kent built on the island. Wyeth also owns a more isolated cottage and studio on Southern Island further south, just off the coast of the picturesque village of Tenants Harbor.

Southern Island is a vivid splash of green in the granite gray blue waters. A bank of wild roses leads the way to Wyeth’s cottage set in the shadow of a lighthouse. As visitors approach from the mainland, a playful Wyeth often scurries out to the lawn and fires off a blast from one of his antique cannons.

With his square jaw, curly brown hair swept off his forehead, Wyeth, now a hard-to-believe 68, carries the mantle of the Wyeth legacy in an easy-going way.

“When the wind is blowing toward Tenants Harbor, I’m sure those folks are yelling, ‘there goes that crazy artist again,'” Wyeth said with a broad smile.

“Ocean is so enormous, such a force”

Wyeth’s paintings of Maine are primarily inspired by life on Monhegan Island where both his father and grandfather also lived and worked. Wyeth prefers the winters, not the height of summer when the island is full of palette-toting painters who mostly want to capture nature’s quiet scenes. It’s the layers beneath the surface and the island’s dark moods that intrigue the artist.

“The ocean is so enormous, such a force,” Wyeth observed. “It changes every day. I’m up here in the winter, and honestly, I almost prefer those times. It’s so stark and the storms roll through and the seas and winds. It’s fantastic.”

Those untamed qualities of Maine come across vividly in “Orca Bates” (1990), a boy who lived on Manana, an island just off Monhegan. Wyeth posed the boy nude, his hair wet and sitting at attention on the hard edge of a massive seaman’s chest.

“He was a wild child, his teacher told me he would jump out of the schoolhouse window,” Wyeth related. “He just fascinated me, so I befriended him and did this series of paintings charting his journey from childhood through adolescence. He was sort of androgynous– boy, girl, and animal.”

In the retrospective show finished works are shown alongside the preparatory drawings and studies. They trace the wide arc of the artist’s development from his childhood drawings at age three through various recurring themes inspired by the people, places, and objects that Wyeth knows so well.

“Jamie’s work has often struck me as a living embodiment of Howard Pyle’s motto– one should paint what one knows,” said Amanda C. Burdan, curator of the exhibition. “When you combine the deep knowledge of something or someone with technical ability the result is a painting that ‘speaks’ with authority. The period of really getting to know a subject is long and once you ‘know’ it, I think it tends to stick with you.”

“Painting is such an individual profession,” Wyeth related. “I’m not performing. There’s no audience. I find painting difficult. I don’t find it easy. I would say I look at myself as just a recorder. I just want to record things that interest me in life.”

Dreamscapes

In 2009, soon after his father’s death, Wyeth dreamed he saw his father Andrew, his grandfather N.C. Wyeth, Winslow Homer and Andy Warhol standing on the rocks at White Head in a storm. N.C. and Andrew obviously share Wyeth’s genetic lineage. Homer was Maine’s best-known seascape painter, though he never painted at Monhegan. Warhol was Jamie’s longtime friend. These four are bound by their connections to Jamie, either directly or through their painting pedigrees.

Painting on cardboard, Wyeth depicts Warhol standing away from the raging sea. Homer stands closer to the water’s edge, walking stick in hand. N.C. and Andy are snug up to the surf, one pointing out a distant feature to the other. The stormy water is a gurgle of white, brown and pink.

In another painting, “A Recurring Dream,” Andy and N.C. stand together in the same spot. Maine writer and resident Stephen King owns a third painting in this dream sequence. Wyeth said he was spiritually moved to make these works, though he is not sure he understands them — and never intended for them to be shown publicly.

“Some dreams are not dreams, they are so vivid,” he explained. “I said, ‘I have to paint this.’ They are very odd paintings. When I look at them now, I think, ‘What the hell was in my mind?’“

There are several other odd paintings in this show: an image of pumpkins tossed from the cliffs at the Headlands, floating through the air like balloons; dogs taking a dip in the water, their eyes fixed in cold stares at the viewer; of another dog staring bug-eyed underneath a great white shark jaw that hangs in display on a wall.

All are interesting and unique, revealing Wyeth’s humor and personality. And none are the kind of Monhegan paintings we have come to expect.

Sin and the Seagulls

After decades of observation Wyeth chose seagulls for the subject material of a 2009 exhibition, “Jamie Wyeth — Seven Deadly Sins” at the Brandywine River Museum of Art. Unleashing dramatic power, Wyeth captures the day-to-day life of the devilish birds as they act out their sinful behavior. Four years in the making, the paintings address human frailty and the sins of pride, envy, anger, greed, sloth, gluttony and lust, a popular Christian theme dating back to the fifth century. They are on display in this retrospective.

“They represent the seagulls for me,” Wyeth observed. “I think the eye of the gull says more than a big, sudsy surf scene. I tried to make the gulls bi-sexual, neither male or female, a little bit of each, because I think women are as guilty of these things as men are.

“One night I awoke from a dream and did these drawings, almost hieroglyphics. In the morning my bed was scattered with them. The drawings kept me on the right trail. I just needed to piece it all together.”

One the artist’s pet peeves over the years is that seagulls have been portrayed in Maine art to look like white doves.

“Seagulls are nasty birds, filled with their own jealousies and rivalries,” Wyeth said. “Most of these behaviors I’ve seen these gulls act out, so it wasn’t a stretch for me at all. I love their independence, that’s what makes them nasty. I love nasty things, and evil sides. So gulls are right up my alley.”

——————-

Terry Conway is a Delaware Arts and Culture writer. You can view more of his work: www.terryconway.net. Contact him at tconway@terryconway.net.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.