A political shakeup could be in store for Pa. state lawmakers under new map proposals

Democrats could have the upper hand if proposals for state House and Senate maps hold after changes and potential court scrutiny.

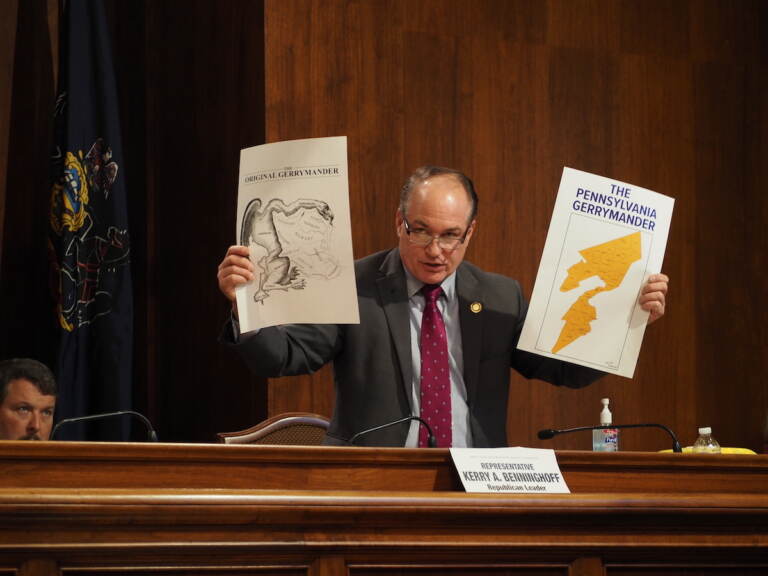

House GOP Leader Kerry Benninghoff holds up an image of a district he thinks is unacceptably gerrymandered. (Sam dunklau/WITF)

Big changes are likely coming to Pennsylvania’s House and Senate.

The bipartisan commission in charge of redrawing state legislative districts every ten years has released draft maps for both chambers.

If passed, they would create maps that are far more competitive for Democrats, while also drawing more than two dozen incumbent senators and representatives into districts where they’ll have to face off against each other — changes that would scramble the commonwealth’s political geography and likely lead to a sea change in the legislature after the 2022 midterms, and for the decade thereafter.

These all-important mapping decisions are being made by the Legislative Reapportionment Commission (LRC), a five-member group composed of Republican and Democratic leaders of both the House and Senate, plus one non-legislative tiebreaker appointed by the state Supreme Court.

That tiebreaker, former University of Pittsburgh School of Law Dean Mark Nordenberg, notes that these maps are merely a first draft.

“Members of the commission certainly make no claim that our preliminary maps are perfect,” he said, noting that this year, they were under a time crunch due to late census data. “In a very real sense, that makes the next 30 days even more important than usual.”

During those 30 days, commissioners will accept public comments and complaints about the maps, then will take an additional 30 days to revise them as they see fit. Any Pennsylvanian who still has complaints after new proposals are released will have the subsequent 30 days to file complaints with the Pennsylvania Supreme Court.

Below is WHYY’s analysis of what the maps will likely mean politically, and how lawmakers and good government groups are reacting.

Partisan or proportional?

Even before the LRC finished presenting its maps, the House Republican caucus blasted out a press release deriding the House proposal as an “extreme partisan gerrymander in favor of Democrats.”

Rep. Kerry Benninghoff (R-Centre), the House Majority Leader who represents his caucus on the redistricting commission, called one of the districts “reptilian” in shape. The district in question, the 84th, is actually a safe GOP district surrounded by similarly red districts. Its shape wouldn’t confer any Democratic advantage.

“In this map, Harrisburg is split. Why? Lancaster is split. Why? State College is split. Why?” he asked. “Reading is split three ways. Allentown is split three ways. The city of Scranton is split four ways. Our team is asked questions repeatedly on these, some of which have not been answered.”

By objective measurements, however, the map does not appear to give Democrats any extreme political advantage.

Dave’s Redistricting App (DRA), a nonpartisan website that produces analyses of political map data, labels the map as “very good” in measures of proportionality, i.e. whether the representatives likely to be elected under a given map would reflect the state’s proportion of Republicans to Democrats.

Democrats, according to DRA, have an average vote share of 52.46% to Republicans’ 47.54% — a number based on a composite of several recent election results.

The number of Democratic seats “closest to proportional” is 106 of the 203 in the House, and DRA finds that the map would likely give Democrats 105.5 seats on average. The Princeton Gerrymandering Project, another nonpartisan map assessor, predicted an even tighter partisan balance in its own analysis — about 102 seats likely to lean toward Democrats.

These predictions aren’t guarantees. Every election is different — some of the races used to simulate an average result, for instance, were contests in which Democrats had especially strong showings, as they did in 2018.

Several dozen of the seats drawn in the proposed House map are also competitive. They could swing toward either party depending on the candidates running, and the political dynamics in a given year.

The Princeton Gerrymandering Project notes that the map is not very competitive — it got an F on the project’s scale — with only about 17 truly contested seats out of 203. Their grading system also gave the map a C, or “average” score for partisan fairness.

Nordenberg noted in his opening remarks, he believes both maps technically skew slightly Republican.

“That is a product of political geography,” he said. “Particularly the fact that so many of Pennsylvania’s Democratic voters live in the southeast corner of the state, which is hemmed in by the borders of New Jersey and Delaware, meaning that it becomes almost impossible to spread them out to have a broader geographic impact.”

The most significant partisan gerrymander that DRA identifies, in fact, is in the current House map.

Republicans have dominated both chambers of the Pennsylvania legislature for the last decade, and particularly in the House, a significant portion of that seemingly unshakeable control stems directly from the legislative maps lawmakers enacted in 2011, and then amended in 2012 when the State Supreme Court deemed them unconstitutional.

DRA gives the current House map its lowest possible ranking in terms of proportionality. The map, DRA says, is “anti-majoritarian” because “even though they will probably receive roughly 52.46% of the total votes, Democrats will likely only win 48.67% of the seats.”

A shifting state

House Democrats were generally pleased with the proposed map.

Rep. Joanna McClinton (D-Philadelphia), the House Minority Leader who represents her caucus on the LRC, said the House map “fairly accounts for the dramatic demographic changes in the population of the Commonwealth since the last reapportionment” — referring to the significant population increases minority groups in Pennsylvania saw over the last decade — and “allows for equal participation in the electoral process.”

Both McClinton and her Senate counterpart, Jay Costa (D-Allegheny), voted in favor of the LRC’s proposed House map, as did Nordenberg. Benninghoff and his Senate counterpart, Kim Ward (R-Westmoreland) voted against it.

The Senate map was less controversial.

All five LRC members voted for it, with Ward noting that while she thinks “there are corrections that are necessary, “it’s important that we … start to move it forward.”

Out of the 50-seat chamber, DRA’s analysis finds that Democrats are likely to win, on average, about 25 seats — slightly less than the 26 seats that a fully proportional map would deliver.

That’s roughly the same as the proportions in the current Senate map. Under it, Democrats hold 21 seats and Republicans hold 28, with one independent senator.

The Princeton Gerrymandering Project said that map had about as much partisan fairness as possible, and average competitiveness.

One key factor that drove some of the line adjustments, particularly around Philadelphia and Pittsburgh, was the changing demographic landscape in Pennsylvania.

The U.S. Census shows Pennsylvania picked up at least 320,000 more people who are Hispanic and Latino in the last decade, and is just over 9% more diverse overall.

Salewa Ogunmefun, Executive Director of voter advocacy group Pennsylvania Voice, said new legislative lines had to account for that.

“This process is really about making sure every citizen has the opportunity to actually elect their own political representation,” Ogunmefun said following Thursday’s meeting. “When we look at Pennsylvania, and we look at the population, and we give respect to those populations that have grown over the last ten years, I think that’s what we see here in these maps.”

The maps would together create seven new districts where a larger number of non-white voters would have to approve a given candidate for them to win election, which Pennsylvania Voice and other advocates asked for during hearings the LRC held before it drew the maps.

Incumbent versus incumbent

One of the other big gripes Republicans have with the new maps, particularly the House one, has to do with incumbent protection.

“In this map, 12 Republican incumbents will be pitted against each other … when only two Democrat[ic] incumbents will face each other,” Benninghoff said. “That’s simple mathematics. In fact, my eight-year-old grandson could figure that one out.”

Pennsylvania law requires that state senators and representatives live in the district they want to serve for at least a year, meaning representatives who find themselves doubled up in a district can’t simply move ahead of the 2022 election.

Nordenberg maintains the maps are not “anti-incumbent.” He noted, legislative maps have historically been drawn with a mind toward keeping lawmakers in the same district. This has created situations in which — as in the current map — representatives who live very close to each other serve different constituencies.

He had to take that into account, he said, even more than he might have liked.

“There is no practical avenue to starting with a totally new map in a commission dominated by caucus leaders whose members live in and have won elections in existing districts,” Nordenberg said. “That is just an observation. I am not making that statement as a criticism,” he added.

Along with the 12 Republican incumbents who, Benninghoff noted, are pitted against each other, two Democratic incumbents are. In four other districts, GOP incumbents are pitted against Democrats. In all four of those cases, the districts in question skew at least slightly in Democrats’ favor.

Rep. Jason Ortitay (R-Allegheny) is one of those GOP incumbents drawn into the same district as a caucus-mate. If the map were to pass unchanged, he would have to face Rep. Michael Puskaric (also R-Allegheny) in a GOP primary.

“It’s certainly disappointing, but we’ll see what changes are made over the next month and hopefully can be worked out to avoid being in the same district,” Ortitay said. “I’m definitely running either way.”

Another lawmaker from that section of the state, Rep. Carrie DelRosso (R-Allegheny), will potentially have to run against long-serving Democrat Tony DeLuca (D-Allegheny) in a district that would favor Democrats about 69% to 31%.

DelRosso noted, she’s beaten an incumbent before. Last year she ousted former House Minority Leader Frank Dermody, who had been in the legislature for decades.

“I just beat a 30-year incumbent, now I’ve got to look at a 40-year incumbent,” she said. “What’s unfortunate is my whole constituency will change now.”

The incumbency competitions would be less intense in the Senate.

Sen. Cris Dush (R-Cameron), found himself drawn into a district that now includes State College, long represented by Senate President Pro Tempore Jake Corman (R-Centre). That potential battle won’t happen, though, because Corman plans to retire at the end of his current term to focus on a run for governor.

The only inter-incumbent race in the Senate that could actually lead to a showdown is between Sen. Lisa Baker (R-Luzerne) and Sen. John Yudichak (I-Carbon). Yudichak is a longtime Democrat who denounced his party in 2019 and now caucuses with Republicans.

Pennsylvania’s gerrymandered history

The last time the LRC was tasked with redrawing House and Senate maps, in 2011, the state Supreme Court ended up deeming them too gerrymandered and ordering the commission to try again.

Where Nordenberg was appointed by a Democratic-controlled state Supreme Court, the LRC tiebreaker in 2011 and 2012, former Superior Court Judge Stephen McEwen, was appointed by a GOP-controlled court.

Along with its lack of proportionality, the House map that resulted from that process had three districts, the 72nd, the 156th, and the 10th, that are not contiguous — meaning those districts have sections that are totally disconnected.

Though Pennsylvania’s constitution explicitly requires legislative maps to be compact and contiguous and to avoid unnecessary divisions, the map stayed in effect for the rest of the decade.

“It’s really pretty awful,” said Carol Kuniholm, who leads the redistricting reform group Fair Districts PA. “It’s one of the worst in the country, by various measures. Most skewed, most distorted, and does a really bad job of representing the people of Pennsylvania.”

As an example that particularly frustrates her, she points to the current 17th House District. It stretches from Lake Erie, down the western side of the commonwealth, all the way to New Wilmington — about 80 miles.

“There’s no reason for that,” Kuniholm said. “It’s just wrong.”

Her group was much more receptive to the newly-drafted maps.

There’s still “lots to sort out with LRC preliminary maps,” the Fair Districts leaders said in a statement, “but on first view these are much more fair [and] open the door for more accurate representation.”

Other good government groups concurred.

“We appreciate the thoughtful and careful approach that the LRC has taken to craft Pennsylvania’s maps,” Khalif Ali, who heads Common Cause Pennsylvania, wrote in a statement.

He added, the preliminary maps “are only the first step in securing a fair, transparent, and participatory redistricting process. The next immediate step is for state leaders to engage the public in a robust, once-a-decade debate.”

In their comments, the mapmakers all suggested there are still things they want to change about the maps. Sen. Kim Ward noted, there’s still another intense month or so of the process left.

“It’s really been a learning experience. I’ve never done this before,” she said, and laughed. “I don’t really want to do it again.”

Get more Pennsylvania stories that matter

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.