A classic you’ve never heard of: Angelina Weld Grimké’s ‘Rachel’ revived at the Sedgwick Theater

In 1916, Angelina Weld Grimké’s “Rachel” was anti-racist propaganda. Now Quintessence says it’s a great American drama.

Listen 1:58

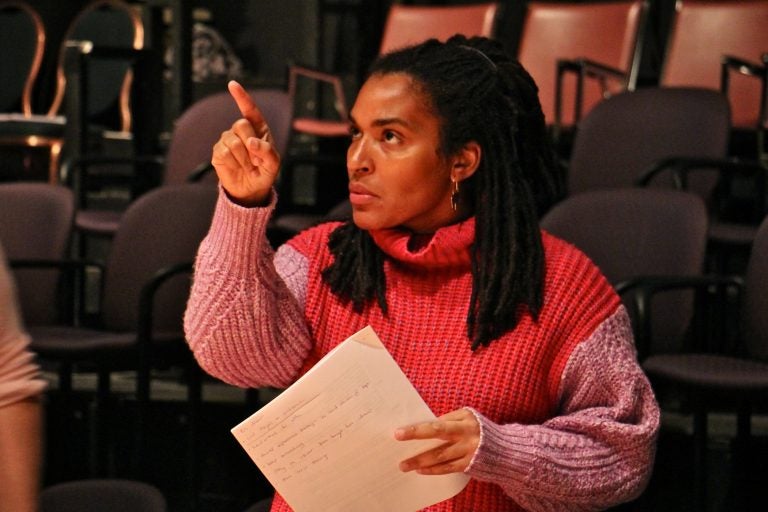

Alexandra Espinoza directs Quintessence Theatre's production of 'Rachel.' (Emma Lee/WHYY)

Since it started 10 years ago as a classical repertory company, Quintessence Theatre, based in Mt. Airy, has presented chestnuts from the canon, from Greek drama to Shakespeare to Oscar Wilde to Samuel Beckett.

For its latest production, it is staging a “classic” you’ve never heard of.

“Rachel,” a drama about an African American family who has migrated to a northern city in order to escape the racial violence of the South, was written by Angelina Weld Grimké, an African American playwright whose parents were prominent abolitionists in Philadelphia.

It was one of the first plays by a Black woman addressing African American issues to be given a professional production. Grimké is best remembered not as a playwright, but a poet associated with the Harlem Renaissance.

“Rachel” was first produced in 1916, in Washington D.C., by the NAACP as a piece of political theater in response to the rampant racism of “Birth of a Nation,” that landmark silent film which drew wide acclaim – President Woodrow Wilson said it was “writing history with lightning” – despite the fact that the Klu Klux Klan were its heroes.

The NAACP felt a need to counteract the film with its own propaganda.

“It’s absolutely a political play,” said director Alexandra Espinoza. “Most theater and art made by oppressed people are political pieces. Their existence as people is political. Some thrive on that, some don’t, but it’s baked into it.”

Espinoza first encountered “Rachel” when she read it while studying African American theater at Villanova University. At the time she found it too bleak and heavy-handed for her liking, saying some of the monologues come off like newspaper editorials.

“There was a movement in the early 20th century, where Black artists were writing to white audiences to inform them of the struggles of the Black community,” said Espinoza, who is Black. “Those plays were not written for me.”

However, once the text of “Rachel” came off the page and into the bodies of actors on stage, Wilke’s humor and warmth became apparent.

“What is so well done in her writing is that she has found a way for all characters to contain the multitudes of how people navigate being Black in America,” said Espinoza. “In each narrative, we see people confront what the world has done to them, and action themselves through hope and despair. Those things are equally valid.”

The plot is centered on a family whose mother does not reveal to her children the fact that their father and older brother were lynched. Fleeing north, she tries to insulate her children from the racial hatred of America, but eventually they discover the truth as adults.

The titular character is the daughter trying to decide whether or not to have children of her own in a world fraught with racism.

Quintessence artistic director Alex Burns says “Rachel” has all the earmarks of classic American theater.

“If a play makes me fall in love, and makes me think about the world in a different way, and also makes me cry, to me it’s a great play,” he said. “It’s a family drama, fundamentally, with a collection of beautiful human beings who go through an extraordinary drama. It just happens that the drama they go through is a national drama, a systemic drama.”

Aside from a revival in London in 2014, Burns has not been able to discover another professional production of “Rachel” since its NAACP premiere in 1916. The reasons for its obscurity can be debated: it might have been too daring for its day, subsequent generations may have found it too political, or, like with so many other plays by women and African Americans, the predominantly white theater community simply took no interest.

As the head of a classic theater company, Burns often wrestles with questions: “What is the canon?” and “Why?” He believes “Rachel” was ahead of its time, but ripe for this one.

“I think we’re ready for it now. This is O’Neill, this is Tennessee Williams, it’s the American drama,” he said. “The fact that the language feels so American and effortless, and so poetic, it’s shocking. Especially considering other plays written in the teens and ‘20s, these insane melodramas. She was writing a new American drama.”

“Rachel” opens at the Sedgwick Theater in Mount Airy on Thursday for a three-week run.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.