A Black bisexual suffragette’s life unearthed in exhibition at Rosenbach

Alice Dunbar-Nelson was a prolific writer, educator and activist from the Victorian era through the Harlem Renaissance. She lived her last days in Philadelphia.

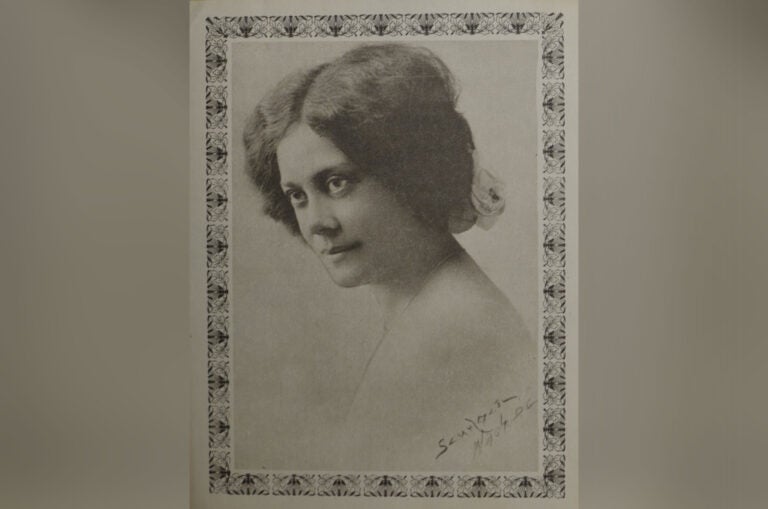

A photograph of Alice Dunbar-Nelson, Washington, D.C. 1915. Photo by Addison Scurlock. (Courtesy of University of Delaware Library, Museums, and Press, Special Collections & Museums, Alice Dunbar-Nelson Papers)

The Rosenbach Library and Museum in Philadelphia is elevating a little-known Black Victorian-era writer and activist, Alice Dunbar-Nelson, with an exhibition of her life and work.

“I Am an American!” was planned for the museum’s exhibition space in its Rittenhouse Square building. Due to the coronavirus pandemic, the exhibit is instead entirely online. Given Rosenbach’s plethora of rare books and manuscripts, the exhibit features digital scans of books, manuscripts, letters, pamphlets, fliers, poems and journals of the Black literary scene circa 1920.

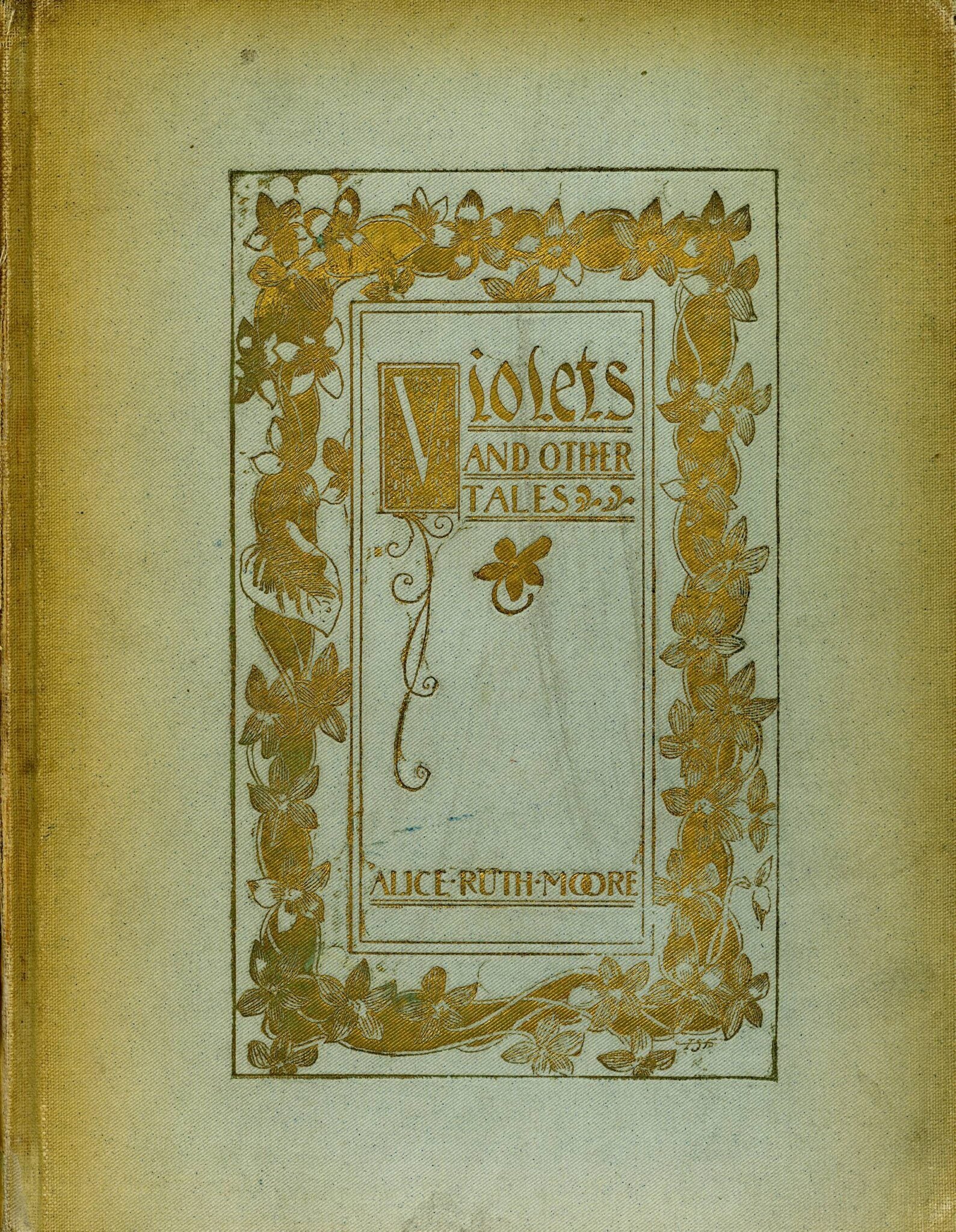

The exhibit has her first book, “Violets and Other Tales,” which contains short stories, poems, essays and book reviews.

Curator Jesse Ryan Erickson first got to know Dunbar-Nelson through her fiction.

“I’m a huge fan of 19th-century fiction and Victorian literature,” said Erickson, an English professor at the University of Delaware, and the coordinator of special collections in its rare book library. “She has a subtle way of approaching a lot of serious and complicated social issues in a way that can be humorous and lighthearted, quick-witted and piercing.”

Her fiction is a gateway to the world of early 20th-century Black intellectual and political life.

Dunbar-Nelson briefly lived in Brooklyn and worked for Victoria Earle Matthews at the White Rose Mission, a settlement house for young Black women in New York.

She traveled among Harlem Renaissance writers, often writing literary reviews for newspaper columns and joining the Saturday Nighters Club, a salon hosted in Washington, D.C. by the poet Georgia Douglas Johnson, which attracted names like Langston Hughes, Alain Locke and Zora Neale Hurston.

While living in Washington, Dunbar-Nelson would socialize with Mary Church Terrell, a civil rights activist who was one of the first Black women to earn a college degree, and Anna Julia Cooper, who was born into slavery and later earned a doctorate from the University of Paris and wrote what is considered the first book of Black feminism, “A Voice from the South.”

Dunbar-Nelson ultimately settled in Wilmington, Delaware, where for many years she taught English at the all-Black Howard High School.

She was also a suffragist, advocating for the passage of the 19th Amendment when the women’s movement had its own racial divides. White and Black women did not always work together toward women’s suffrage. Dunbar-Nelson reached out to bring Black men on board for the women’s right to vote.

“When the rights of the race are an issue, the women will stand with the men on the matter,” she said in a speech to Black men in Harrisburg, according to the Washington Post. “By doubling our vote, we will then be able to show to the oppressor that we are a factor that should not be despised.”

Later in life, after the passage of the 19th Amendment, Dunbar-Nelson moved to Philadelphia and worked for the American Interracial Peace Committee, a partnership between Black Americans and Quakers to enlist African Americans into peace organizations.

All the while, she kept writing essays, stories and pieces of journalism. In 1914, she edited and published “Masters of Negro Eloquence,” a collection of the best Black speeches “from the days of slavery to the present time.”

Dunbar-Nelson also wrote what she hoped would be the great American novel: “The Lofty Oak,” based on the life and work of her mentor, Edwina Kruse, principal of Howard High. It was never published.

Erickson said Dunbar-Nelson never used her fiction as a hammer for political activism.

“It comes across in her correspondence: She considered the didactic style, that was more upfront about addressing issues head-on, as propaganda,” Erickson said. “She wanted to touch the universal cords of the human spirit. She didn’t want to turn people away by being too abrasive when touching on delicate topics.”

“I Am an American!” is based largely on archival material held at the University of Delaware, the main repository of Dunbar-Nelson’s papers. While she might not be a household name, Erickson said her papers are the University of Delaware’s most popular archive for researchers.

Dunbar-Nelson’s interests and accomplishments are wide and “I Am an American!” is presented through an extensive website organized by theme into eight sections by representing her rich and varied life, including her involvement in literature, her work in education, her activism and her journalism.

She was married to Paul Laurence Dunbar, the celebrated Black poet and writer whose place in history is solidified by having written lyrics for the first all-Black musical to play on Broadway, “In Dahomey.”

However, as “I Am An American!” points out, Paul was an abusive husband.

“One incident was particularly egregious where she was sexually assaulted and physically abused,” explained Erickson. “It puts an unfortunate stain on Paul Laurence Dunbar himself, in my view. It causes us to reconsider his place in history.”

The marriage lasted four years, ending in 1902. Paul Laurence Dunbar would die four years later. Dunbar-Nelson kept his name. Over her lifetime, she changed her name several times: Alice Ruth, Alice Ruth Moore, Alice Dunbar. For the purposes of the exhibit, Erickson settled on Dunbar-Nelson.

Dunbar-Nelson married two more times, first to a physician named Henry Arthur Callis and then to political activist Robert Nelson. During that time, she also had a romantic relationship with her boss and mentor, Edwina Kruse, at Howard High.

The details of her life were revealed in the 1980s when her diaries were published as “Give Us Each Day.”

“I’ve read the diaries several times. Ah! It’s such a poignant and inspirational roller coaster of a book,” Erickson said. “You get a sense of a woman that is both in control of her life — an assertive woman pushing the future that she wants to see — but being challenged by insurmountable forces working against her, and confronting those challenges with open eyes: being discriminated for her gender, her race, dealing with complicated issues surrounding her sexuality.”

I Am an American! is meant to be an introduction to Dunbar-Nelson for people in Philadelphia, where she lived the last years of her life. Erickson also hopes Dunbar-Nelson serves as a role model for the next generation.

“In Philadelphia, there is a large community of Black Americans that will benefit from hearing this story, and young Black girls in particular who will look at Alice Nelson-Dunbar’s life and legacy and see it as an example of what can be achieved, despite negative racial stereotyping and discrimination that one must face growing up in this country,” he said. “I’m speaking as a Black man, so I know what that looks like.”

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.